Interest in South African photographer Ernest Cole’s recovered negatives rages around the world

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

He may have died many years ago, and the time he was yet to be celebrated as one of South Africa’s foremost photographers who documented the life and times of South Africans.

Their lives tormented by apartheid, and their human dignity degraded and demeaned by the apartheid laws, Cole captured in his photography all the nuances that several of his generation of photographers in the 1950s and 1960s could not. That is the distinguishing feature of his art practice from his generation photographic documentation of a people under the grip of a horrible system designed by men with ill intention. He died in exile.

However Ernest Cole, is very much alive today, many years after his actual demise. The now famous photographer’s new lease on life is thanks to his images he took many years ago and that were regarded as lost. But in 2018 the negatives were found safely kept in Sweden. This treasured collection is currently doing rounds around the world, as they are quite seminal in their depiction of the cruelty of apartheid practice on the black body as well as tormenting black people’s souls, clothed in those bodies.

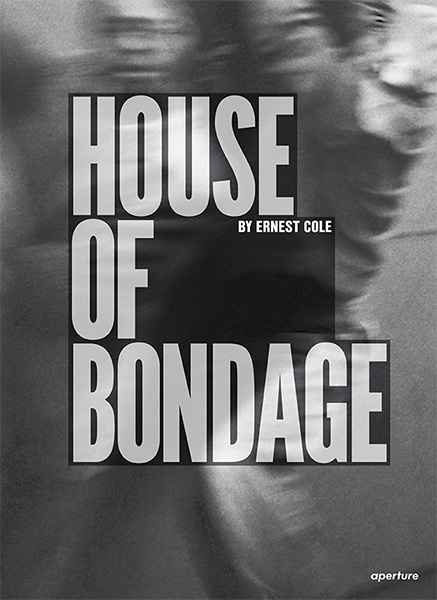

Long forgotten and thought to have been lost forever, these images that the photographer took along with others when he left the country for exile are now being shown in galleries and are getting collectors livid as they try to outbid each other to lay their hands on the collection in art auction houses’ floors around the world. A book about this ‘lost’ and ‘rediscovered’ collection, published last year, and now on the Best seller shelf at Exclusive Books, has clearly increased the value and therefore demand on the collection.

“First published in 1967, Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage has been lauded as one of the most significant photobooks of the twentieth century, revealing the horrors of apartheid to the world for the first time and influencing generations of photographers around the globe. Reissued for contemporary audiences, this edition adds a chapter of unpublished work found in a recently resurfaced cache of negatives and recontextualizes this pivotal book for our time,” says Amzon.

The results are yet to come out about Art Aspire Art’s latest auction which took place in Parkwood yesterday, June 7, 2023, where a series of 12 photographs from the family trust were put up for sale to collectors in an auction session that was live as well as accessible to collectors from around the world virtually at the same time.

We are honoured to present a portfolio of twelve of the most iconic images from lauded photographer Ernest Cole’s seminal publication House of Bondage (1967). They have been printed from Cole’s ‘lost negatives’ (only rediscovered in 2018 in Stockholm) by Dennis da Silva, South Africa’s premier black and white photography printer, and released through the Ernest Cole Family Trust in South Africa,” says Aspire in a statement accompanying the exhibition catalogue.

Of high socio-historical and cultural value and importance, photographs from House of Bondage have been exhibited worldwide at various prominent institutions including SFMOMA San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Barbican Art Gallery in London; Fowler Museum at the University of California, MODERNA Museet in Stockholm and the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town.

A selection of photographs is currently on view at MoMA in New York. In June 2023, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation in Eschborn will open the first major exhibition in Germany dedicated to Ernest Cole, showcasing 130 photographs from House of Bondage. Other recent exhibitions include FOAM Fotografiemuseum in Amsterdam, until 14 June 2023; SMART Museum of Art, at the University of Chicago and the TATE Modern, London until 19 July 2022.

The book, titled Ernest Cole: House of Bondage that carries this collection in Coffee Table format, in which are essays by prominent names in the cultural space, including South African poet Laureate Mongane Wally Serote (Foreword) was republished last year by Aperture. Other contributors to Ernest Cole: House of Bondage, released in December 2022, are Oluremi C. Onabanjo and James Sanders.

House of Bondage, itself an item of interest to collectors, is clearly playing a major role in the resurgent interest in Cole’s images. Therefore through the photographer is long dead, he is currently living though his work that is connecting with the living. This in a way seems to affirm the belief that an artist does not die, as only the body dies and his work will assume a new life for the dead artist. This is certainly true in the case of Cole.

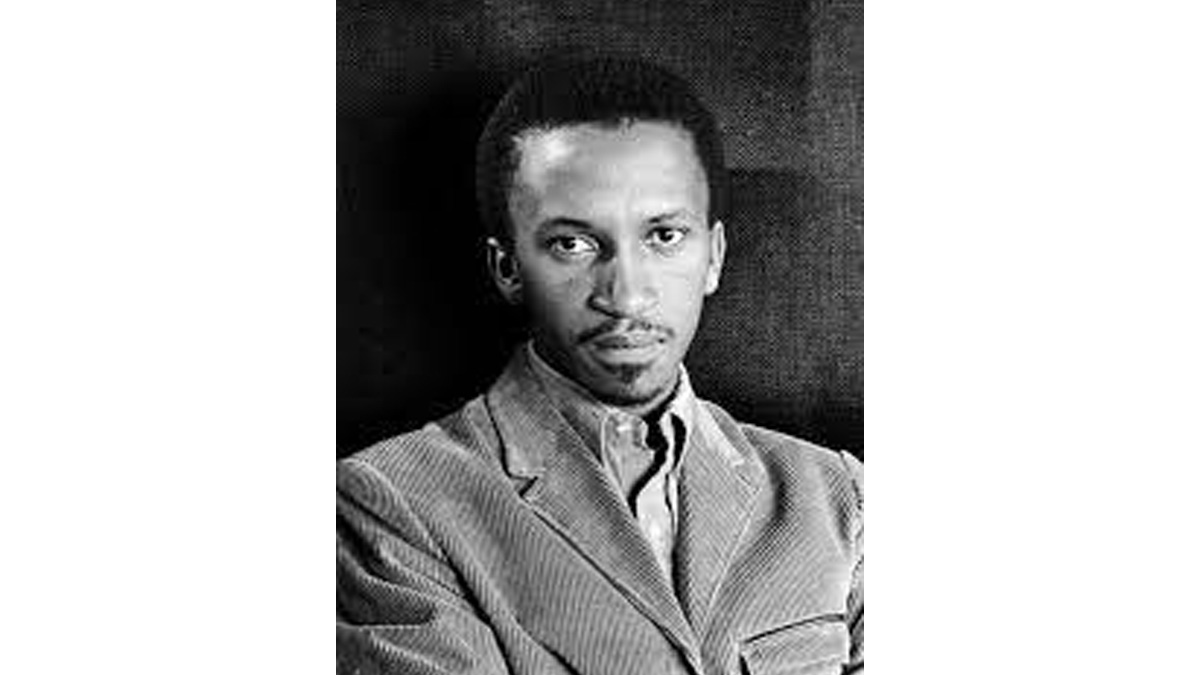

But who is Ernest Cole

The story of Ernest Cole is similar to other South Africans classified as black. He was not spared from the social engineering and distortions of South Africa. South African History Org. takes up history of tenacity and resilience.

“Ernest Cole was born on 21 March 1940 as Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole, in Eersterust, Pretoria. He left school when Bantu Education was introduced, and unsuccessfully attempted to complete his Matric (Grade 12) via correspondence through Wolsey Hall, Oxford, due to financial constraints.

Cole therefore went to search for a job, but was hindered by his lack of matriculation and by the laws governing South Africa at that time. In terms of these laws Cole was defined as an “unskilled labourer” who could only work as a messenger, tea-maker or floor sweeper.

His break came when he was employed as an assistant to a Chinese studio photographer. This is where he obtained basic knowledge of photography, and an old Yashika twin lens reflex camera.

Cole then found another job as a floor sweeper and messenger at Zonk Magazine, an Afrikaanse Pers competitor of Jim Bailey’s Drum magazine. While working tat Zonk, he saved up enough money to put down a deposit on two Nikon rangefinder cameras and a few lenses.

In 1958, Cole went to Jurgen Schadeberg – Drum magazine’s chief photographer – and asked him for a job. Schadeberg took him on as his assistant in design and production. During this time, Cole registered for a correspondence course with the New York Institute of Photography. With help and encouragement from the staff at the Institute, his idea of recording apartheid in South Africa was nurtured.

After Drum, he moved on to the Bantu World newspaper (later called The World and now known as The Sowetan) where he was given a job as photographer. In the early 1960s, he started to freelance for clients such as Drum, the Rand Daily Mail, The World and the Sunday Express. Cole was therefore South Africa’s first black freelance photographer.

Cole managed to outwit the Race Classification Board when he was re-classified as a Coloured by changing his name from Kole to Cole. This gave him more privileges and he was soon able to leave South Africa. On 9 May 1966, he left for France, England and New York to showcase his apartheid project and photographs.”

.Ernest Cole: The House of Bondage is available at local book shops in South Africa and on Amazon, among other outlets globally.