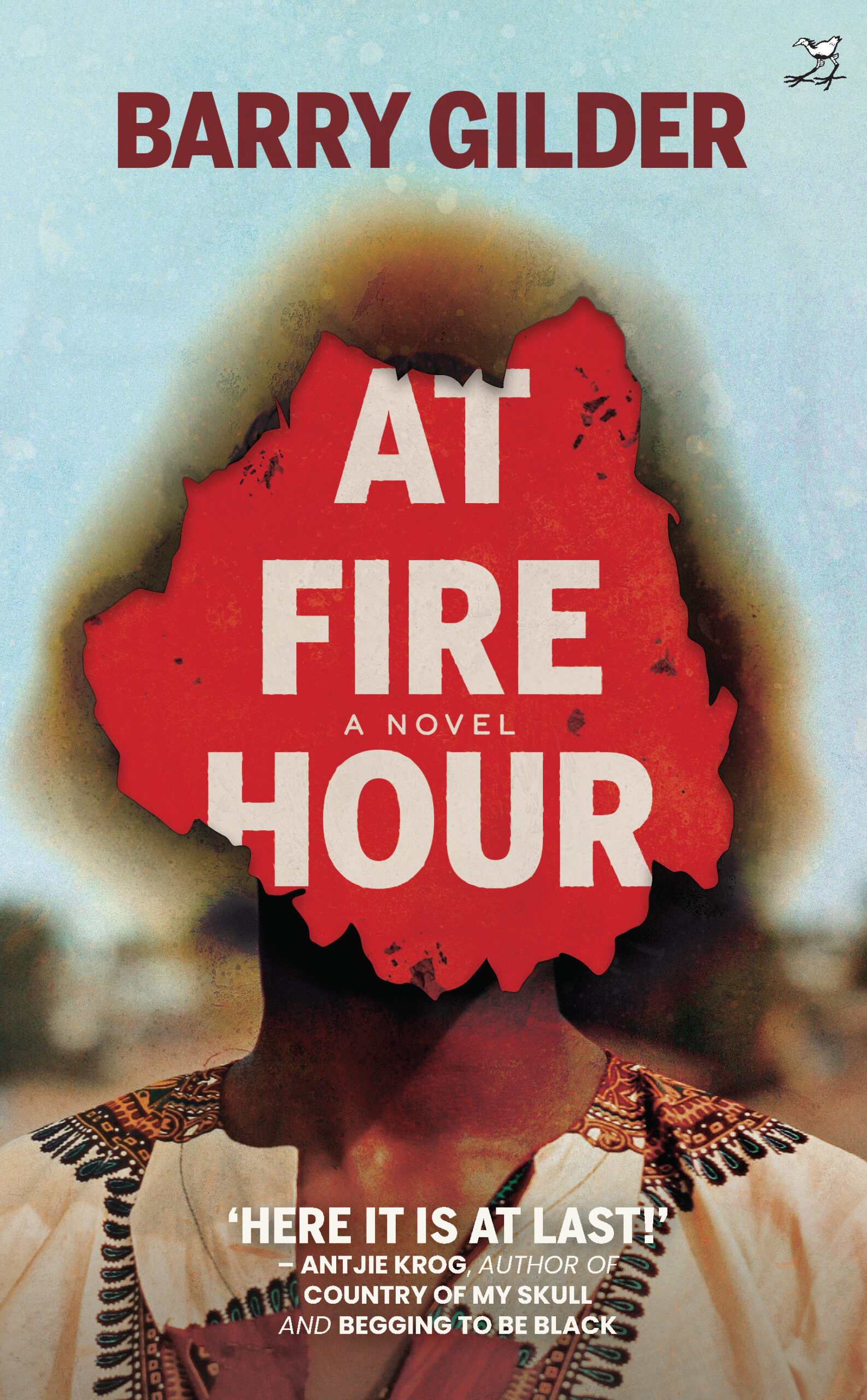

At Fire Hour, a novel that is not about spying written by someone with inside workings of the intelligence community

Title: At Fire Hour

Publisher: Jacana Media

Author: Barry Gilder

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

In reading Barry Gilder’s new book, a novel titled At Fire Hour, the first thing that will strike you is the use of the characters of famous real people and real events, especially of a cultural nature, such as the writers conferences and music festival that too place in various places, featuring South Africans. These took place during the struggle years against apartheid, when several of these people that include writers, musicians, painters and politicians and activists were scattered in exile to fight for South Africa’s freedom.

These events and characters some of whom are still alive, such as writers Barbara Masekela, Wally Serote and Mandla Langa, for example, their roles in the struggle have this way been immortalized by At Fire Hour in their life times. Others however have since passed on, including poets Willie Kgositsile and Lindiwe Mabuza, novelist Nadine Gordimer and musicians Jonas Gwangwa and visual artist Thami Mnyele. However these characters of real people are well melded with characters that Gilder created. The melding of real characters of real people and the events that actually took place, has been done so well that at the end, it does not really matter whether a character is that of a real person or the one that exists in the imagination of the writer.

But all characters, without exception, and the real events that took place are used in a fictional sense and almost in all cases, what the characters say or do in the book, has nothing to do with what the real people said or did. This, the writer emphasizes in a disclaimer. This is something that Gilder also told me when I met him at a Killarney, Johannesburg in a coffee shop a few weeks ago. He was in the country promoting At Fire Hour. He had come back to the country from Damascus where he is South Africa Africa’s Ambassador. “Of course it is an issue that was raised by my supervisor Ivan Vladislavic, but people who are alive and whose characters I have used have no objection, such as Wally Serote and Mandla Langa,”he told me.

Using really characters and featuring real events capturing a particular period, elevates At Fire Hour as a realist novel. Instead of being a weakness of the novel, it is actually its strength as you will enjoy the fiction part of it, while at the same time learning more about the issues that affected and defined the struggle lives of many of the people, some of whom, such as Gilder himself, are in government today.

Gilder has had a colourful life himself, that of a musician, a songwriter and singer in the National Union of South African Students, before leaving South Africa to go into exile in the 70s to join the ANC singing struggle songs in anti-apartheid rallies in the UK, received both military training and intelligence training in the Soviet Union. In democratic South Africa, he became a central figure in the country’s intelligence services as Deputy Director-General of the South African Secret Service, Deputy-Director-General of the National Intelligence Agency and Director General of the Department of Home Affairs, among other senior government positions.

Post these government positions however, the literary bug seems to have hit him as he has written quite a number of critically acclaimed books, including non-fiction book Songs and Secrets: South Africa from Liberation to Governance (2012), the novel The List (2018) and now At Fire Hour (2023). All the books (with the exception of the first which was co-published by Hurst and Jacana Media) are published by Jacana Media. And the former spy boss takes his writing career so serious that in retirement he decided to go back to university to study writing, acquiring a Masters Degree in Creative Writing and a PHD in creative Writing from the University of the Witwatersrand. At Faire Hour was in fact the product of a part of his PHD work at Wits.

Despite Gilder’s protestation that he does not want to be regarded as a spy, but a novelist, I guess we cannot run away from who we are, as somehow the things that we make a career out of, have a tendency to manifest themselves in several aspects of our other lives. And so does At Fire Hour in several respects, mirror the life that has defined Gilder’s life for years working in the intelligence structures of both the ANC in exile and the post-apartheid government?

In fact At Fire Hour, the spying world plays a major part of the main characters lives, but beautifully told in such a way that it does not come out as if it is about the world of spying. The novel is a story of one Bheki Makhathini, a fiery poet who after the 1976 student protests, finds himself forced into exile after being brutally tortured by the Boers to try without success, to force him to reveal who his ANC handlers in exile were.

But as fate would have it, after surviving the torture by the Boers, he is again tortured brutally in Zambia by the ANC after a love rival concocted lies that he was an apartheid spy.

I will not go further than that as I would not like to spoil your reading pleasure. But if you will allow me, let me tell you that a lot of things happen involving a number of characters. A number of these things will make you angry sometimes about the abuse of power, pettiness even when people are fighting a war for a good cause.

But without feeling as If you are being taught a history of the struggle, you will inevitably learn about the dilemma that those who fought for the liberation of South Africa faced while doing so in exile. On one hand, there was a real issue of infiltration of the ANC structures in exile by the enemy, and on the other hand, it was understandable why there was so much paranoia within the ranks of the leadership. However on the other, you also wonder how easy it was for someone to claim without proof, that a comrade was a spy, and got that comrade into serious trouble such as the case of Bheki Makhathini.

This happened when Bheki’s love rival, an obnoxious double agent called Chief Mlungisi for personal reasons, falsely claimed that the talented poet was a spy. He did this even as he very well knew that Bheki was not, but he in fact was. His issue being that Comrade Pumla fell in love and married Bheki as she spanned Chief Mlungisi’ clumsy demands for a romantic liaison between them. This is even as Comrade Pumla told him very clearly that she was not interested in him, but Bheki, the poet. Can you then imagine the pain of being tortured by the Boers while in South Africa, and then being tortured again by fellow comrades while in exile based on lies made by a losing love rival over a woman comrade?

This work of fiction works at different levels, one of which is the ongoing conversation within the liberation movements, especially within the ANC on how some innocent people were branded spies and got tortured in camps for nothing really, while the real double agents remained untouched.

So many innocent people were branded a spy because of personal clashes during the struggle that they suffered torture and other un-describable harm in the hands of comrades, those who were in the trenches claim till today. This therefore makes At Fire Hour one of the most important books, work of fiction as it is, which gives an insight into the workings of the ANC in exile and the dilemmas of spies within the organization. It is also a book that tells the personal stories of those that went to exile to liberate South Africa. But there is more to the book.

As a reader, you will be offered an opportunity to be introduced to a wide range of world literature. From Russian literature, Western literature to South African literature. From Tolstoy to Nadine Gordimer and Alex Laguma. The writer uses a wide range of literary devices within his range of knowledge, such as the epistolary letters the main character writes to his imaginary late professor. The writer also critics the works of number of writers using the main character of Bheki Makhathini to do so. That way he can get away with saying anything and everything about the work of other writers without putting himself on the firing line, so to speak.

This is because writers have the right to turn a character into anything, such as an extremely ignorant or stupid character, or, as in the case of Bheki Makhathin, an extremely gifted wordsmith. Everything depends on the purpose a character has been created for by the author and the role that the character has to play to make the novel work. Another example is the character of Chief Mlungisi, who is not only misogynistic, but “a blood agent,” to loosely quote Julius Malema, the leader of the EFF and a former leader of the ANC Youth League. Gilder needed these two characters who are worlds apart in their intellectual inclination to drive the narrative in this novel. And it works as you are bound to get angry, very angry about the things that befall, such a hugely talented writer who is 100 percent committed to the liberation of South Africa at the same time. This is a book you must consider in your collection.