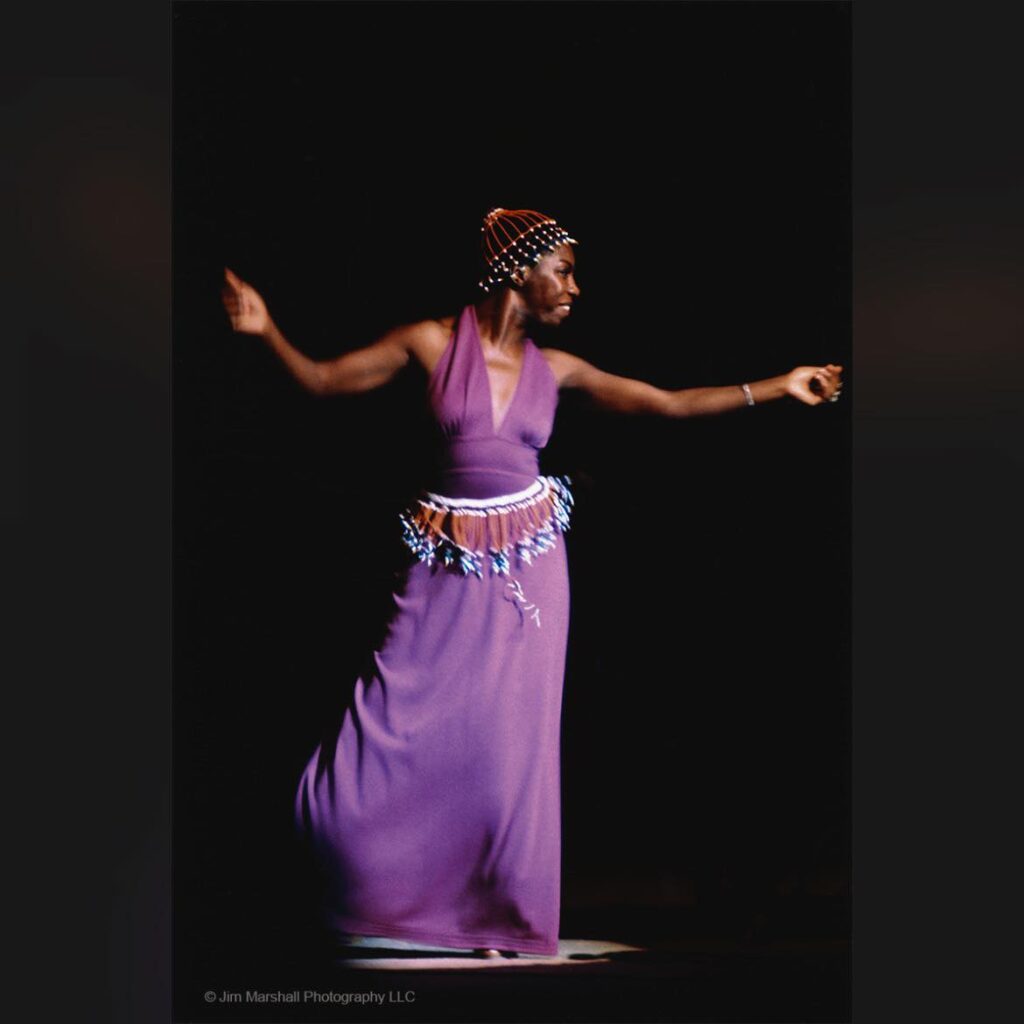

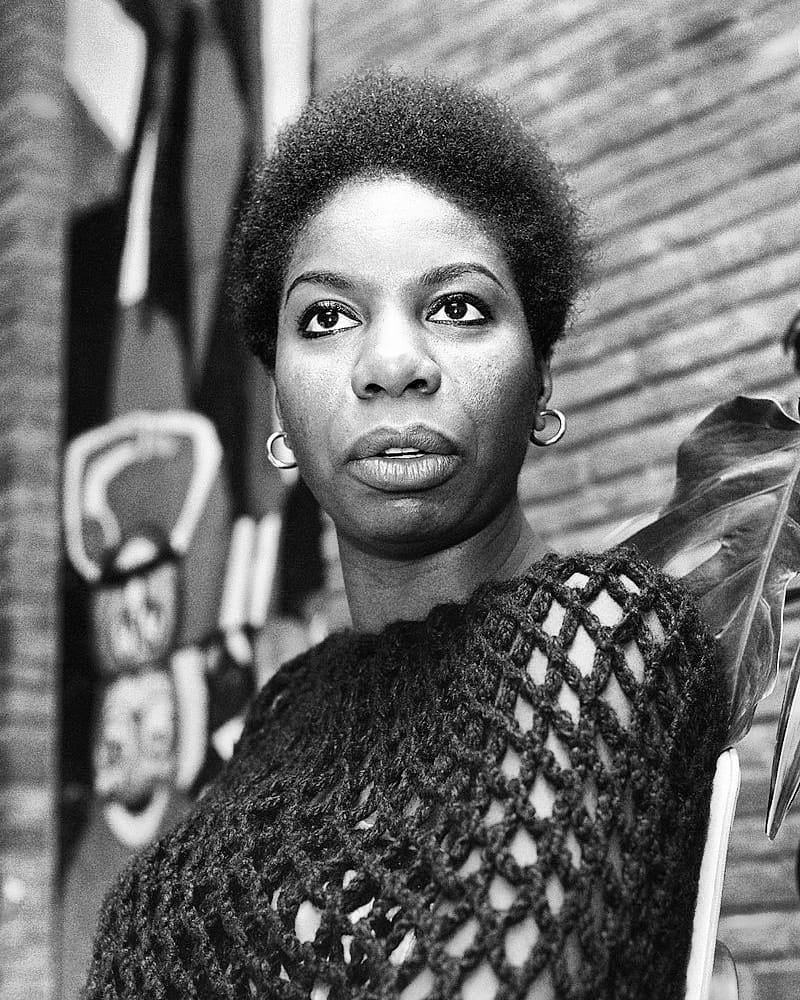

Unpacking Nina Simone’s myth of a complex life: A mentally unstable person, freedom fighter and influential pop culture icon

By Joy Greyling

Nina Simone, is perhaps one of the greatest performers to ever live, continuing to influence popular culture with even rapper Kanye West sampling her in his “Blood on the Leaves” (Yeezus 2013). But what makes Miss Simone even more notable, is her dedication to the civil rights movement of the 1960s in America.

Growing up in the Jim Crow South, it was always Nina’s dream to be the first Black woman concert pianist in America (What Happened Miss Simone? 2015). Though she never fulfilled this particular dream, Nina inspired, and as Maya Angelou points out, was loved by millions. Yet it should not be taken for granted that Miss Simone chose a life of unhappiness.

As a feminist, she became what Sara Ahmed terms, a feminist kill joy. To be a kill joy, as Ahmed explains, in Feminist Killjoys (And Other Willful Subjects), is to choose a life of unhappiness. This unhappiness is not choosing to be unhappy, but rather an unhappiness that is expressed in relation to the world around you.

There is in other words, an unhappiness with the way in which the world works. A feminist killjoy, is outspoken in her beliefs, and therefore will call out the power structures that cut across race, gender, sex, class and culture (Ahmed 2010).

What does it mean to choose the path of the feminist kill joy and its associated unhappiness? What in other words, does it mean to choose a life of opposition in 1960s America as a Black woman with mental illness during the civil rights movement?

When we think of these particularities in relation to Nina Simone the various intersections of her identity must be stressed–that of a Black woman with mental illness. Black women’s experiences cannot be read in a single axis framework, an idea that Kimberle Crenshaw speaks about, as their identity intersects both race as well as gender.

In this essay, I look at Nina Simone as a Black woman living with bipolar disorder during the 1960s. Denying a single axis framework of her life, I will investigate Nina’s affect on the American nation by looking at the various intersections of her identity. I will demonstrate how someone as influential as even Nina Simone becomes demonised and a subject of fear by looking at language as a builder of barriers, these barriers between people or bodies with the use of affect theory.

Affect, can be understood as the social response we have to the way in which our bodies, respond to stimuli. Affect, occurs before we experience emotion, and is therefore, not a personal feeling but an experience of intensity that sits outside of consciousness. Actions, affect other bodies, and the way in which this affect shapes, is mediated by social as well as cultural norms (Introduction to Affect Theory: Brian Massumi & Eve Sedgwick 2019).

It is my argument here, that language does not just describe the world, as stated by Eve Sedgwick but writes the reality of the world. In the way that Nina Simone is written about, spoken about and remembered, the use of language is employed to establish difference, to shape “us” and “them” boundaries.

Even shockingly, in texts as recent on her legacy as 2015. To illustrate this, I look at an extract from Austin Bryant’s article in Noisey titled The Other Woman Inside Nina Simone: Why the High Priestess of Soul Is Making a Comeback (2015).

What makes Simone’s legacy so challenging is the dark period of her career. After leaving the country in 1974, she bounced from Liberia to Switzerland to France, with small stops elsewhere in between

At one point, almost destitute, she was found wandering the halls of a hotel naked, wielding a knife. Later, she would set her own home in France on fire. Friends found her in a state of shambles and slowly helped her resurrect her life and career. The once mighty “High Priestess of Soul” reached the bottom, but, through performing in her later years, she recovered some of what was once lost. Exiled abroad, Simone hid in the shadows of her mental illness.

Like the misbegotten mistress in The Other Woman, Simone ultimately spent much of her life alone and without a lasting partner…

From this extract it becomes clear that Nina Simone as an individual, outside of her celebrity status, is read primarily as mentally ill, and as a woman, who lived during the 1960s. Constantly her mental illness is stressed in a negative light. The seriousness of her mental condition, that of bipolar disorder, becomes parody.

The image of the unstable, the dangerous and the violent is projected onto her in Bryant’s descriptions of what can clearly be understood as a psychotic ‘episode’. Yet there is an implied judgement in these words. When we read, “she was found wandering the halls of a hotel naked, wielding a knife,” the first conclusion that the ‘normal’ or the ‘healthy’ mind would make is that this person is unstable, dangerous and a threat.

It is not that the words in themselves are the problem in this particular instance, but rather that the image painted by them leads to certain problematic associations, that of either the angry black woman, or the murderess.

It is interesting to juxtapose this Nina here, the Nina, naked with a knife, with the freedom fighter that was not opposed to reaching her goals by use of violence. A school of thought that is not uncommon to the civil rights movement in particular or any country that suffered under colonial and imperialist powers.

Yet, the kind of fear we speak of when we think of Nina as a civil rights activist, is very different from the fear that Bryant shapes when he speaks about her mental sufferings.

We do not fear, for example, a terrorist, which people like Nina Simone were often called as a result of their political allegiance and affiliations, in the same way that we fear the mentally ill. The fear of the terrorist is on a nation scale, and affects the nation which by its composition of consisting of various people, affects the individual.

The fear of the mentally ill is different, as the mentally ill, generally speaking do not have allegiances with one another and approach on an individual level. Therefore the state cannot protect individuals from an ‘attack’ from the mentally ill.

From the first sentence quoted here by Bryant, the stigma against the mentally ill is normalised as he refers to Nina’s period with intense mental health struggles as a “dark period of her career”. It is problematic to infer that mental health struggles are a “dark period”.

He does not stop there but continues to smear Nina Simone’s legacy by the use of violent language, making of her, a spectacle as he mocks her with statements such as “the once mighty ‘High Priestess of Soul’ reached the bottom”.

Implying here that a psychotic break which Nina was in all likelihood suffering from on a number of accounts – including abuse from her ex-husband Andy Stroud, discrimination, the lack of monetary income due to her activist allegiance, as well as having to take care of her young daughter, Lisa.

A stressor for any mentally ill person when they are hardly able to take care of themselves due to such an ‘episode’ (this will be the last time that I use the word ‘episode’ as it implies that the mentally ill are an “episode” to watch, much like a soapie.

I will now speak of lapse). Therefore, when Bryant states, that she was “once mighty” he is actually saying that as a result of her mental health struggles, she has lost her status as the “High Priestess of Soul”, hitting the “bottom”.

He continues, “Exiled abroad, Simone hid in the shadows of her mental illness.”

In this statement, Bryant makes it seem as though Nina had no choice, as though she was exiled as a result of her mental health, which of course is not true, but his use of langue here implies as much. This is a single-axis reading of a Black woman’s life who dared to choose the path of unhappiness.

Even in her death, in the year that Bryant attacks her so viciously, 2015, she is discriminated against as she was her whole life. It’s not enough for him to insult her based on her mental health. Bryant even goes as far as to insult her based on her love life, showing a patriarchal understanding of womanhood.

I state this as when we speak about heterosexual, cis gendered men, it is not necessary to consider their lovers or the fact that they were, for example, “alone”. He expresses, “Simone ultimately spent much of her life alone and without a lasting partner”. In as far as this is a fact, he does not take into account the isolation and loneliness of suffering from bipolar disorder.

Bryant’s writing on Nina Simone completely strips her of her agency and reads ethnographically, detached and cruel. It is my intention to show here, the affect of Nina Simone on the American nation with a reading that refuses a single axis framework such as Bryant’s.

I will investigate Nina’s affect on the nation by looking at the various intersections of her identity which, seems to be often ignored in retellings of her life.

We are often presented with only two views of Nina, a duality, which, of course is because her life is simply viewed as “either”, “or” as we see in Bryant’s reading. When Nina is no longer seen as the wonderful and talented performer with an “androgynous voice”, she is regarded as mentally ill, specifically as bipolar.

Her life, her existence is divided into two halves, ‘healthy – famous’, or ‘bipolar – life in shambles, dangerous, violent’. It is important to note here, that, often times mental illness, especially bipolar is only thought of in manic phases as well as psychosis within society, due to a lack of proper education as well as media portrayals on the subject, where many individuals garner their information from.

There is however bipolar that is not manic, and neither depressive, there is a bipolar that is stable, as a result of managing the illness which is often overlooked. Unfortunately, for Nina Simone, psychiatric drugs were not as specialised in the years that she was diagnosed as they are today, and the medication she was put on to ‘manage’ her illness, cost her her talent, normal motor function, and much more.

When Nina was diagnosed with bipolar mood disorder, commonly referred to as manic depression at the time, she was placed on Trilafon. The side effects of this medication was a nervous tick on her face, her voice slurred, and she was no longer in control of her movement, this affected her music skills significantly and her ability to perform became restricted (What Happened Miss Simone? 2015).

Funny enough, Bryant refers to her mental health lapse, as “the bottom”. In the example above, one of numerous that speak about bipolar individuals on the internet, it is the affect of language that is demonstrated and the way in which it shapes our ideas and understandings of the world around us, in this case our perception of Nina Simone, a mentally ill, Black woman in America who lived undiagnosed for the greater part of her life (Nina Simone was only diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the 1980s).

The way in which Bryant writes about the songstress, activist, mother and wife, Nina Simone, results in accompanying emotion. Emotions have the ability to move between bodies and can be collectively experienced (Ahmed 2004: 117). They result in a creation of boundaries, resulting in “us” and “them” thinking.

As Ahmed explains, there is a creation of an imagined other, this other is a threat. Our imagined other in my example is Nina Simone who represents the mentally ill, women, Black people as well as Black women.

What does it mean when we think of Nina Simone as an imagined other, and who are the subjects that are bound together through emotion against her in this “us” group?

I would like to argue that Nina Simone was never read as an individual and was instead read as not only an angry black woman, but as the angry Black woman who led a group of Black people who were angered because of the way that Black people were being treated in America.

Nina Simone was not only the “High Priestess of Soul”, but became a face of activism and violent protest. After the murder of four Black school girls in Birmingham, Alabama by a white supremacist, Nina wrote Mississippi Goddam which has been described as “furious”, “darkly playful” and expressed “black anger in a way that never had been heard in American music before” (Lynskey 2015).

Nina Simone thus became the subject of fear in her embodiment as one of the leaders of a movement towards the improvement of the lives of Black people in America. She can be regarded as much a ‘threat’ as any person that stood up for the rights of the Black community in America at the time, such as Dr. King, Malcom X, James Baldwin, Stoklely Carmichael and Langston Hughes who Nina Simone freely associated with (Lynskey 2015).

Nina grew tired and took up her role as the feminist killjoy she was intended to be. Her wilfulness shows a break from the former Nina Simone, not only of classical music initially, but of jazz and soul as she traded these existences for one of vocal protest. Her songs of protest, would unfortunately lead to the decline in her popularity as a songstress as she was read by the nation as a political message.

She became the politics she stood for. Sadly, not only did Miss Simone lose her fame due to her political allegiances, but she left the civil rights movement depleted, feeling that the rights she so fought for were never won.

well-known quote from her was that freedom looked like “no fear”, and it is the fact that she continued to see a life of fear not only for herself but for the black community that makes me believe that she lost her hope in the civil rights movement and being an active participant in it (What Happened Miss Simone? 2015).

This example, indicates the nature of affective emotion and the way in which it circulates. Nina becomes not an individual of fear but becomes representative of a collective of fear, a community. Hate is economic and has the ability to move between signifiers in relations of “difference and displacement” (Ahmed 2004: 119).

In an affective economy emotions such as in the example of Nina Simone as a complex, intersectional individual, and her involvement with the civil rights movement, we see that emotions align people with communities and bodily space with social space through the intensity of social attachments.

In this case it would be the civil rights movement (and Nina as a face of it) against the state and constitution. In this mediation of relationship between the psychic and social and the individual and the collective, we see the establishment of the us and them boundaries that made of Nina a part of the “them” reading, as a result of the single axis framework that she is read by.

Specifically in language, and my excerpt of Bryant’s we see that emotions work as a form of capital and that affect itself does not reside positively in the sign but is created as a way in which it is circulated. Emotions are distributed, according to Marx, in the social and psychic field. This movement between signs lead to affect.

Affective economies are social, material and psychic (Ahmed 2004: 119). It is the failure of emotion to be located in a particular body, object or figure that results in emotions to (re)produce the effects that result from them.

However, emotions as affective economy, in the way that I have been using it, relates to fear and the materialisation of bodies (Ahmed 2004: 121). Fear always has an object or subject and travels between bodies resulting in, at the time, the activist body becoming the body of the ‘terrorist’ and its associated fear. Ahmed explains in her example of the nation and the asylum seeker that, the “us” group live in fear of being replaced by the “them” group.

Language becomes a tool of othering, and shapes boundaries, making people afraid of those that are not a part of “us”. This is what happens in my example.

As the nationalistic, conservative subject fears losing a “place” and “position” that they believe, belongs to them. Hate circulates economically, working to differentiate some from others (Ahmed 2004: 123).

I conclude thus, in agreement with Ahmed that fear is not about defending borders but instead is about creating them. This is done by erecting objects of fear for the subject resulting in a separation. Some objects are spoken about in such a way, with language borders, that they are created to be more fearful than others.

Throughout this text I have shown the way in which language as well as a cultural artefact such as Mississippi Goddam can be misplaced, and result in an affect negative emotion towards a particular group or individual in the way in which emotions circulate between bodies towards a particular group or individual in the way in which emotions circulate between bodies.

.Joy Greyling, an activist, archivist, writer and curator has just completed a Master of Fine Art Degree at Wits.