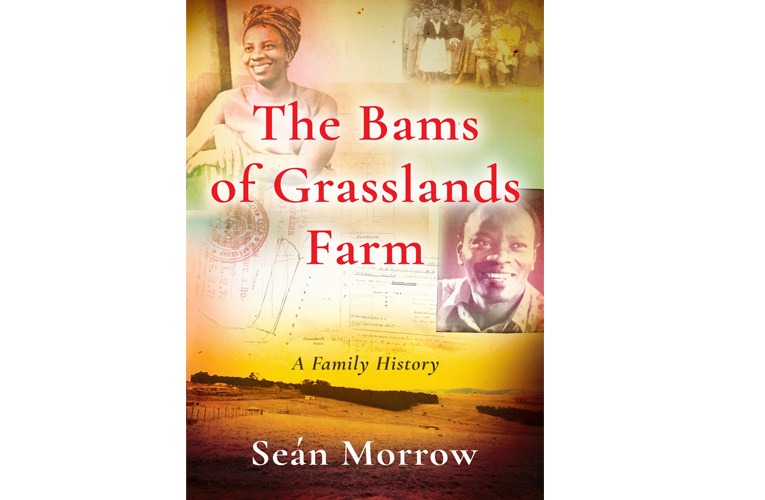

Newly published book The Bams of Grasslands Farm is a long overdue tribute to one of South Africa’s prominent families

By Jojokhala Mei

Hot off the printing press to close 2024 lands TheBams of Grasslands Farmby Sean Morrow,

The book inevitably focusses on the landed middle class homestead’s two famous siblings, 91year old Brigalia Ntombemhlophe Bam; and her inimitable deceased brother and ex-Robben Island prisoner cum lawyer, Judge Fikile Bam. Brigalia is the graduate social worker and prayer woman best known as the iconic, internationalist, graceful and authoritative yet never egotistic former Chairperson of South Africa’s Independent Electoral Commission. Traits she shares with her brave, merry, and influential brother best remembered as “Fiks”. Probably “The Fixer” too. As elites the family benefitted from the spoils of the oppressors, only to rise up against them. Both are arguably Scions of the Bam family since Brigalia restored the family chapel on the farm, and has built her own homestead there. On Saturday 07 December 2024 at 2pm Book circle Capital at 27BOXES on 4TH Street Melllville Johannesburg is a treasured book signing.

Here is an extract of directions to a good holiday read – Rhabul’aaphaUngafinci!

“Princess Magogo had strong moral views., particularly on the importance of virginity for unmarried girls, and she supported Brigalia’s village work. Her son’s car, NMA 1, was at her disposal when she required. Brigalia overcame any misgivings that might have been about her as an outsider and marshalled a potent combination of tradition and modernity in her work with rural women,

…..

Brigalia and her mother were in fact involved in activities that the authorities would certainly have considered political. Money arrived from the Defence and Aid Fund in the United Kingdom, and a committee in Durban of which Brigalia was a secret member allocated funds. One of Temperence Bam’s activities in the Pholela area was to support the destitute families of imprisoned political activists. She used the monthly Defence and Aid allowance that arrived via her daughter to assist them and provide them with food from the Health Centre garden.

…..

Brigalia shuttled between Durban and the Rand. She revived the organization among black women – teachers, nurses, businesswomen – in places like springs, Benoni, Krugersdorp and Randfontein. The city women learnt crafts like crocheting from her, and how to make chutney; she learnt to make salads other than the interminable rural beetroot salad, ‘native salad’ as her friend Desmond Tutu jocularly called it, and, and from one of Dr and MrsXuma’s daughters, how to make coleslaw. Temperence Bam was an expert baker, in her mother’s German tradition, but the Rand women made unbeatable tarts; they brought apple rats all the way to a baking competition in Natal. The Transvaal won. This the authentic texture, feel, and taste of black middle class South African homes, influence by Western models, not at all in the ebullient west African style, but for all that unmistakably African.

The difficulties and humiliations facing black professionals, especially a woman, were many. Black women in natal were perpetual minors, under the guardianship of their male relatives, in Brigalia’s case ostensibly her brother Fikile, imprisoned on Robben Island. After repeated applications she obtained exemption and was then entitled to manage her own affairs. In the ‘tribal’ discourse so dear to the authorities of the time, she was ‘emancipated and freed from the control of her legal guardian and (was) vested with full powers of a kraalhead’, now able to own property and make contracts in her own name.

If she flew on aplane she would have to sit on the back seats, and if the plane was fully booked, she could be ejected from the flight to make room for a white passenger. She could not stay in hotels. The automobile association would not register a black driver.

On the highways it was necessary to plan stops at isolated stops because at garages and elsewhere there was a ‘Ladies’ toilet’, or a ‘Gentleman’s toilet’ and a ‘Boys Toilet’, but no toilet for black women. But, Brigalia says, she never felt as protected by men as then. Especially on her main route between Durban and Johannesburg she stopped at garages where she was known and the black attendants would smuggle her into the white women’s toilets and watch out for her. She would go to the hatch for serving food for blacks, ‘and you know what? I had the bet sandwiches … and sometimes I didn’t pay the full amount! And these were my friends. … They were proud of this black woman who’s driving alone’.

In 1967 Brigalia left the YWCA for the WCC in Geneva. There, she would be part of the campaign for the ordination of women; of agitation for changing the image of omen in the mass media; of work to expose sex tourism in Thailand; and of a host of other encounters and campaigns. She would visit places a s remote as Fiji and as potentially hostile as the Soviet Union. However, at the YWCA she was involved with people with backgrounds like that of her childhood and youth, while belonging to an organization with international reach. ‘In my whole career,’ she says, ‘that’s the job I enjoyed most.’

(STAGING POST PUBLISHERS (2024)