Lady with perfect timings pleads for working patience with our marginal freedom

By Jojokhala Mei

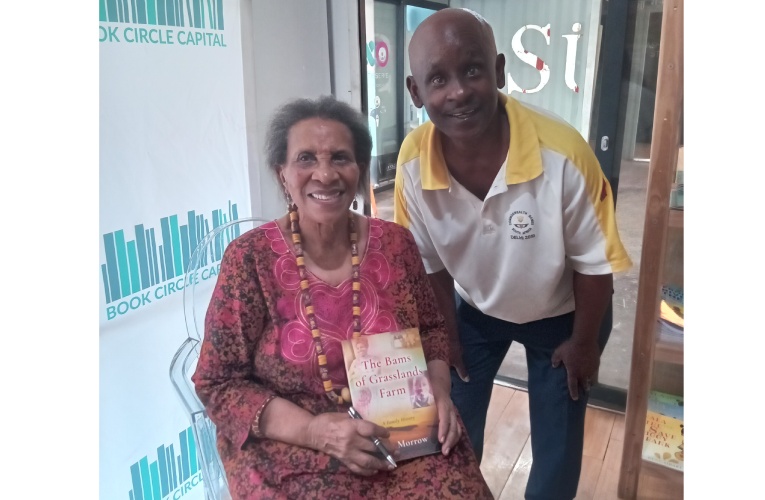

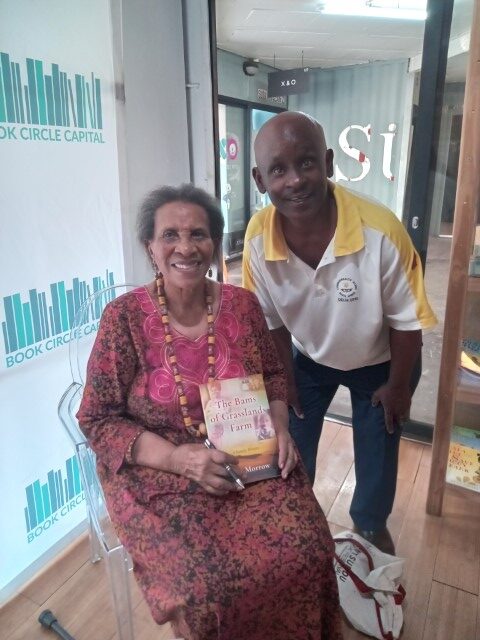

Splendid and mellowed 91year-old ex-Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) Chair, Brigalia Bam, copiously signed copies of the daring The Bams of Grasslands Farm by Sean Morrow two Saturdays ago, November 7 at Book Circle Capital in Melville, Johannesburg. Excitement was in the air, not least after citylifearts published an extract the previous day.

Book Circle Capital host Sewela Langeni kindly grilled the enduring ever articulate icon about the tact in telling her birth family’s history in the book, before setting the cat loose for admiring literati pigeons and family questions. With a zeal and sharp mind that belies her age, Brigalia obliged.

Firstly, she was third-time lucky to successfully lure historian Professor Sean Morrow in Britain to come here to research and pen the Bam family history from her 1800’s great-grandfather, Solomon, who secured the whole family a farm and colonial western education prestige ever since. On the stories she heard of her grandfather she easily quips: “How I wish I’d documented the stories of his childhood.”

However, this book inevitably focusses on Brigalia Bam’s and her and her equally famous deceased ex-Robben Island prisoner big brother Judge Fikile Bam. The brave judge of infectious humour went by the moniker “Fiks”, while the devout sister of Ndebelesque ‘prayer woman’ fame, also called Hlophe, equally made her mark amongst village and township women countrywide as a social worker who channeled British solidarity Defence Aid funds to suffering families of political prisoners in the remotest villages imaginable through her own mother, Temperance..

You can’t miss the irony that her friendship with royal Inkosazana Princess Magogo, and rides in her son’s car, to remote KZN village women, decades before those warm relationship helped quelled volatile elections during her helm at the IEC. The book sneaks an evocative Black & white photograph of her and other photos, plus the colour pictures of the dear historic family chapel she restored, and her own snug village hideout from Pretoria. Sewela, on the other hand, spills beans on another book secrets that as a girl Brigalia had her dad’s permission to ride horses seated astride like men. Imagine the famous ‘last of the Mohicans’ charging on horseback.

Her two decades professional self-exile in Geneva Switzerland spearheading the World Council of Churches’ campaigning for the ordination of women in churches turned out to be perfect timing for her high-pitched voice when international pressure on South Africa to change blew sky high with sanctions and so on. She sneaks in that she even grabbed the opportunity to introduce the then exiled ANC president Oliver Tambo to the WCC.

Another perfect timing should be tireless advocacy for the South African Council of Churches on return to South Africa because it took the good word of another church luminary and future presidential Director General, Reverend Frank Chikane, to seal a place heading the IEC.

When one of the audience pigeons, former journalist Sandile Memela, quizzes her on the value of aligning with White power, like the Bams did, Brigalia Bam says that was the modus operandi of Black Economic Empowerment, but laments that “Economic structures have been hardest to change,” or “The class thing has hit us hardest.” On her truckful skills of leadership to also tackle the angry young men in particular. she calls for “levers used to gain traction”, “How you learn a skill of loving people’’, ‘Taking the worst of them seriously”, “women generally have not been part of institutions”, “you need a war of persuasion.’ She says she misses the education of her time to influence “Your ethics. Your values. How you spend your time. … not just a certificate to get a job.”

After a long chorus of jovial quips, pulling faces, and loud asides, she settles down to signing books for what she calls “Christmas money” it is clear that Brigalia Bam wryly admits to the ironies and challenges of life, like the sons whom their mothers call the ‘men of the house’; but always finds hope in her prayer.