New female sculptor to look out for in SA

The Southern African Foundation For Contemporary Art (SAFFCA) an organisation that was founded in 2015 to promote emerging contemporary artists from southern Africa, and their work, has announced the inaugural recipient of its Artist of the Month award. The first artist to be honoured is KGAOGELO MASHILO who practices as COW MASH. Writer BONTLE TAU takes us through the art practice of this new talent to emerge out of South Africa.

By Bontle Tau

Cow Mash describes her current work as: “inspired by her self-given name “Cow” which she correlates to cultures and symbols of the cow within the Sepedi traditions, as well as globally. Through cow metaphors, she tries to situate herself between the traditional and contemporary world. Cow creates drawings on synthetic leather and sculptural works using synthetic wools, combining various fabrics. She reflects on the transformation and evolution of culture by using synthetic leather rather than authentic cowhide. Her doodle-like, repetitive lines in her drawings and meditative approach to sculpting are a means of self-contemplation, healing and finding a sense of belonging.”

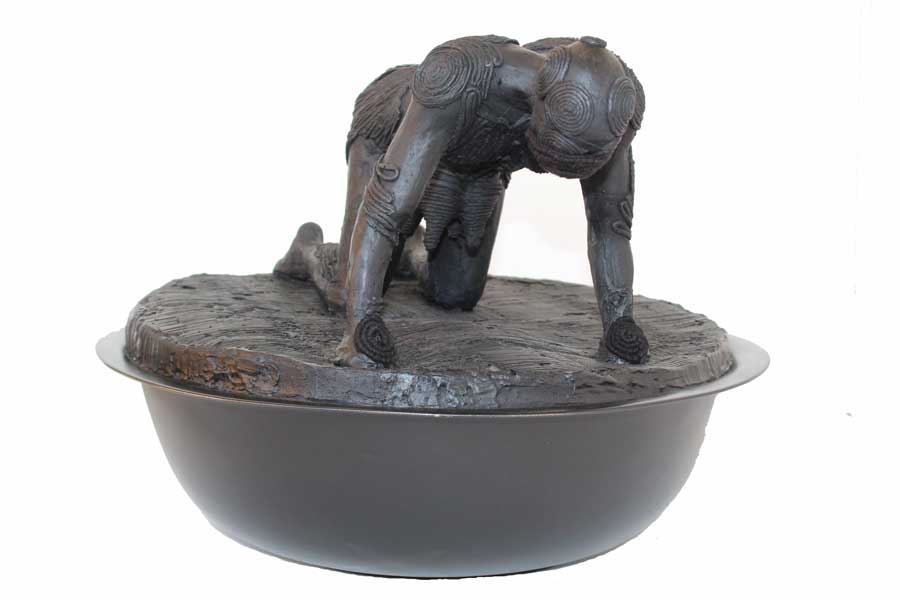

Kokomoga means ‘to swell’ in Sepedi. In this sculpture, the enamel bowl is reminiscent of family functions where cooking for large groups is accompanied by the use of this type of bowl. “My mother tells me of the olden days when they would bake fermented steam bread, they would cover the bread mixture with a grass matt and leave it in the sun to ferment. The swollen bread could take on the print of the grass matt that acted as a lid for the swelling.”, says Cow Mash. In Kokomoga Cow Mash creates a texture, using the grass matt that her mother refers to above and places a figure on all fours on top of its surface. The grass matt or what one can refer to as a rug or carpet in this case, can be seen as a metaphor for concealing one’s personal troubles – this being inspired by the popular English idiom: “sweeping things under the rug”. The work unveils multiple meanings, which slowly begin to unfold as one engages with the artwork. In the first instance, one sees the female ‘cow’,that the artist refers to, in a position of tribulation as we find the figure physically brought to her knees on all fours in subservience.

Upon a second reflection of the figure and the pose it assumes, we see a resemblance of the four-legged cow in a standing position, which for the animal, represents fortitude and strength. In a third reflection, the kneeling position on all fours that represented tribulation in the first instance can also be seen as position of prayer. Reminiscent of the surrender most of us are taught to take in our early childhoods, we are reminded that this surrender can bring forth a renewed sense of internal empowerment. The beautiful dichotomy of this work sees a figure that appears at first to be literally and figuratively “brought to her knees”; yet the inevitable rising of the surface that this ‘cow’ rests on reminds us that she is returning to strength and overcoming everything that had initially brought her to her knees, as the inside of the bowl underneath her begins ‘to swell’ or Kokomoga.

Through her work, Cow Mash is able to present the viewer with both an inward and outward perspective on domestic affairs; and in doing so she contextualises matters of a singular household within other widely inclusive concepts and larger conversations like those of culture, belonging, and social status. By merely zooming into the inner workings of a traditional Sepedi home, as she experiences it daily, these works open up space for broader thoughts and interactions through their unravelling. Conversation of intimate spaces of domesticity and introspection that one finds in these works, manage to reflect, with utmost subtlety, on topics that address contemporary cultural narratives. As the primary foundation for the artwork

Kokomoga, Mash makes of the very specific enamel bowl – an object which is immediately associated with an African household upon the first glance. Choosing to elevate a pre-supposedly mundane object like this as part of the artwork, organically makes this object a visual memento for African culture. The humble act of placing a female figure on enamel bowl brings about an association with one of core aspects African womanhood.

Womanhood is explored further and celebrated in The Herd portrait series as the artist questions the notions of individuality and belonging – more specifically of who or what something or someone might belong to. There is an ambiguity and open-endedness in Mash’s subtle word play heard and herd. Yet again a closeness is here underpinned by the notion of listening to a particular voice, and the significance of that very same voice within a collective. While gender roles in this work only sit in the conceptual background and are merely touched on, they seem to rest in the psyche, brewing further questions that extend beyond the original domestic platform.

One cannot interact with Cow Mash’s work and ignore the powerful symbol of the cow that she pays homage to throughout her oeuvre. A symbol which is immensely significant to African households which serves a beacon for nobility, marriage and social status. The symbol of cow is invaluable to African domesticity and identity. It has been the traditional bridge for joining households for generations and will continue to do so for the generations to come. A simple four-legged creature, that retains both an inward and outward position in the African home allows for a dual perspective on a culture that seeps through the under belly of the African continent.

In conversation with Pierre Lombart, about these particular works, the use of the word “domestication” became prevalent throughout. We often discussed how artists can express the celebration of the daily chores. Which can be found the opus of Jan Vermeer, or even closer to us, in the works Usha Seerjam. Beauty emanates from the mundane.

However, this domestication does not go unchallenged. The cow for example, originally a free wild being that has now been tamed and domesticated to a famer’s will, with a tag and an enclosure to prove it. Women are seemingly not exempt from this narrative of domestication, indeed they are placed in the enclosure of a household, and surrounded props designed for their role, like brooms or aprons. The question remains unanswered as to why the woman is considered the ideal candidate for this domestic role. This is a matter that is grappled with further than the boundaries of the African continent for a large majority of women. It remains a marvel to see the level of intricacy evoked by Cow in her as launchpad for critical thinking. A resilient appreciation resides with us after engaging with Cow Mash’s work. With sincere gratitude, one hopes that Mash will continue to contribute to the visual art culture in this humble, yet truly impactful approach.

.Those interested in collecting Cow Mash’s work can contact SAFFCA at foundation@saffca.com.