Entering the Devil’s play ground: The Prison

By Musa Kheswa.

A blue card with full names, prison number and the conviction. Sosobala fiddled in his back pocket and stole a glance at his interrogator while taking it out. He was a one-eyed man with tattoos of playing cards on both sides of his scrawny neck, which looked like it could snap under the weight of his gigantic head. The prison clothes, as orange as the sunrise, hung from him like wet clothes from a line.

“Another killer,” one-eyed man said, twitching his eyebrows. “I need soldiers like you, you feel me, who aren’t afraid of spilling blood.” A prisoner with tattoos of an ace of spades and a king of diamonds would be the highest ranking member in the 26 gang. For every kill, whether a sky-bird or a gang member or a prison official or even a gang leader, a tattoo of the appropriate playing card was inscribed onto that convict’s body. Just like the medals of honour bestowed on a soldier.

“Call me Chopper, moth’fucker. In here, you either join my soldiers—the 26s,” he said, “or you become a sky-bird. You wouldn’t want that, right?” It was more of a directive than a plea. Pledging to be part of a gang was most sacred, yet a cursed oath in jail where you chose to live or die by it. To take up the number lore of the prison gang was to accept that your gang leader was your god, that his word was final. And his orders were to be executed to a T with no questions asked. The 26s crouched and raised their right fists, thumbs up, in front of their faces when engaging each other.

They were the capitalists of the prison who would give anybody, even prison officials, a bloody fight if they dare stood in the way of their money-making. The 27s, they were the assassins who took no sides and only looked out for number one. The 28s were the ravishers who preyed on anything, young or old, quick to poke a hole in anybody they thought deserved one.

“My lieutenants will fill you in on the 26s’ number lore straight away,” Chopper said. “Thereafter, you’ll have to earn your stripes, moth’fucker.” Sosobala nodded like a child as he realised that earning his stripes had everything to do with spilling blood.

As the days went by, he picked up the monotonous prison routine. At four-thirty in the morning, the lights came on. At five o’clock, it was roll call. Convicts stood to attention next to their beds whilst the warders counted heads. After that, the sky-birds did their beds and cleaned the cell. They would place rags under their hands and knees, and then kneeling on the linoleum would shuffle backward and forward like horses. Some of the soldiers would hop onto their backs and ride them as if they were in a Horse-Ball competition. Thereafter, it was shower time, at your own risk.

At nine o’clock they walked in twos, marching downstairs with their plastic containers and cutlery to the cafeteria for breakfast. It was porridge with one teaspoon of sugar, two slices of plain brown bread, and cold tea. After that, it was recreation time where they chilled outside the corridors of their cell blocks, in the four-by fifty metre courtyard.

During that time, some convicts who had influence were allowed to exercise at the gym facility centre. And the soldiers would be hard at work relieving the sky-birds of their valuable possessions, or engaging in low-key drug dealing. At two o’clock, again, they marched to the cafeteria to be dished up with an afternoon meal. It was pork, or minced fish, and meat curry with no condiments, served with samp or mealie pap. It would be accompanied with five slices of plain brown bread. Chicken and rice were luxuries served only at Christmas.

If there was a smell of uncertainty in prison, like a gang war where the stabbings took place on the ramp or in the cafeteria, or if their rights were rescinded, they were lined up outside the cells. And by three o’clock another head count was done, and then they were locked back in the cells.

The sky-birds would be compelled to do their washing, using the barred windows to hang it out. They did the ironing too, by putting clothes in their beds between the sheets and the blanket, and sliding on them until they were ironed.

On weekdays the gang leader flanked by his most trusted lieutenants would summon his soldiers to the chambers, in the far end of the corner of the cell. They crouched in a ring for briefings. It took three hours or so. That was where the soldiers placed their daily takings-money or valuable stuff relieved from the sky-birds, or traded-in the centre of the ring. The gang leader would then educate them about the number lore or talk about new strategies to control merchandise flowing in and out of prison. Or he would discipline those who challenged his authority. It was not a pleasant sight. It was gruesome until Sosobala got used to the stabbings and the reek of blood.

And then the gang leader would keep what he desired from the daily takings, and the rest was traded off to other cell blocks. It was more like economics: Who was it who’d made that statement, where in a comparative advantage, the first party traded for what they had less of, with the second party that supplied more of that, in ex-change for what the second party had less of.

Then a carry-bag, using sheets, was used to transport those goods to the upper and lower blocks whilst lieutenants guarded the trade-offs like hyenas hunched over their kill.

After business was concluded and all parties satisfied, it was time for some entertainment. That was when the sky-birds stooped to their lowest levels—singing karaoke and performing dance moves or acts beguiling the gang leader and the soldiers until the night lights were switched off at ten o’clock. Soon after the lights go off, high-pitched sex sounds, reverberated in the dark of the cell.

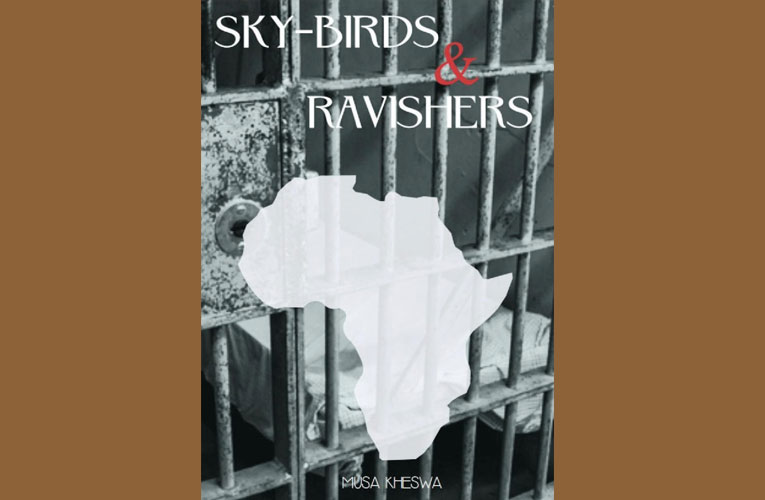

.This is an extract from Sky-Birds & Ravishers by Musa Kheswa. Published by Liyasa Publishers. Available online and from all good bookstores. Recommended Retail Price: R289.