Calling for black people to regroup after many centuries of colonialism and rid themselves of inferiority complexes

Review: By Rolland Simpi Motaung

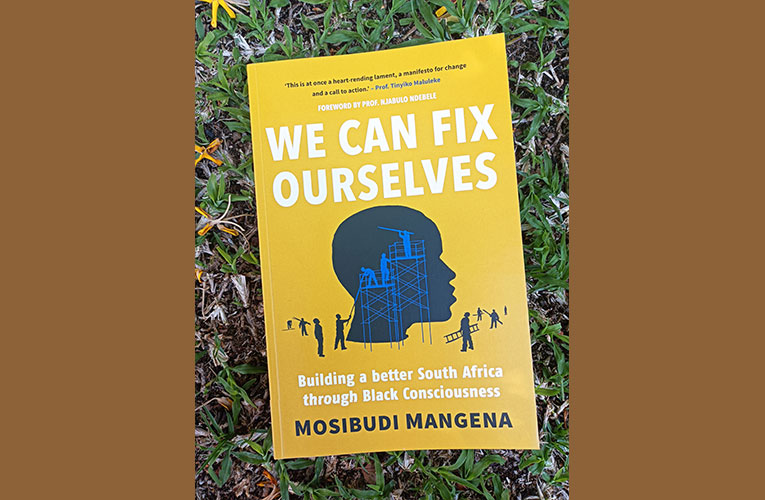

Author: Mosibudi Mangena

Title: We Can Fix Ourselves: Building a better South Africa through Black Consciousness

Publisher: Kwela Books (2021)

Black Consciousness (BC) as described by Bantu Steve Biko in his various speeches and prolific book I Write What I Like (1978) is essentially about liberating black African people from psychological, economic and physical oppression. In this latest offering We Can Fix Ourselves, political activist Mosibudi Mangena, strives to revive and realign this Black Consciousness ideology into the contemporary democratic context.

In his introduction the author states that the book seeks to promote BC in various spheres of our lives, such as health, education, transport, food and the arts. Other areas where BC could play a role in offering solutions, the book also explores the disordered management of crime, particularly the insecurity of black women and children; looting state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and as well as the neglect of home languages.

The book mainly argues how as a society we could find effective solutions to the socio-political and psychological issues particularly black African majority with BC philosophy as the drive force.

IS BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS STILL RELEVANT?

The oppressions against the black majority in South Africa that Biko spoke of in the 1970s are unfortunately still evident even today. In this book Mangena argues that although we have attained democracy there is still a lack of genuine psychological, economic nor physical liberation, meaning that democracy does not automatically lead to psychological liberation.

At its core BC is a resounding call towards decolonizing the minds of black communities in order to reclaim their rightful place in the land of their forbears and to further carry that self-worth wherever they may live around the world. The author states that Black Consciousness “calls on black people to regroup after many centuries of colonialism and rid themselves of inferiority complexes”. He further emphasizes that BC is meant for black majority to self-define, reclaim their value system, culture, religion and overall outlook to life. Over and above the quest for individual liberation for the poor and unemployed black majority, some may wonder if indeed BC philosophy is the ultimate solution we all have been waiting for.

For instance if BC was evident in the public sector could state capture; load shedding and general lack of service delivery be curbed? STRENGTHS OF THE BOOK: Some of the strengths of this easy read are based on the practical proposals of where Black Consciousness could be applied in various key sectors such as education, health, economy and political leadership. In regards to education the book argues that the majority of educators need to bring back love for education and for their learners as one of the values of BC. Nibbling on the revolutionary Che Guevara, the author stated “in education perhaps even more than in revolution, it’s much harder to think of the teaching profession without love for children”.

The book affirms that other BC values such as dignity, human worth and solidarity should be infused in children, from early schooling years through to university. Specifically in regards to early childhood development is where the decolonization of the mind should start, argues the author. Practical actions such as conversing and reciting rhymes in the children’s mother tongue, and playing with toys that reflect them and their culture should be promoted, the book suggests.

Over and above the decolonization agenda the book encourages that such practices in our education system and home should be a natural way of learning that reflects contextually relevant content for the black majority.

The opening chapter The Health Scene is one of the stand outs filled with many references and case studies of healthcare workers and activists from the 1970s and 1980s. Through their own expense these health practitioners drove various health care initiatives across South Africa particularly in black communities. For instance, the author celebrates the work of Dr. Abu Baker Asvat who led a community awareness project (Chap) established under Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO) health secretariat.

Apart from other passionate doctors building health centers and clinics in rural- township areas, other key figures the book mentioned are Dr. Tshehla Hlahla who did house calls and treated community members who couldn’t offer medical services free of charge.

In essence the author argues that all these health care practitioners were rooted in the BC philosophy hence the utmost love and dedication was shown to their communities. In comparison to this current democratic context the author states “in the majority of cases, it is not the only lack of money that is a problem, but lack of care, love, respect and application to duty at different levels of health care”.

Although the author didn’t comment on the recent (Personal protective Equipment (PPE)s corruption scandal and mental health challenges in a COVID-19 environment, he concludes that we need more love; kindness and humility in putting patients’ lives first as a way to practice BC.

SHORTFALLS OF THE BOOK

Regardless of the strengths of the book, there are some arguments that may be contradictory and ambiguous that may obscure the crux of the book’s message. For instance in regards to the issue of language, the author seems to be harshly opposed to the English language. However puzzlingly he wrote this book in the same “colonial language” creating a contradictory element in his approach. One only wonders if the book will eventually get to be translated in his home language as a practical effort to lead by example to promote BC fundamentals.

The author also claims there are no publishers, bookstores and literary outlets that offer literature in African or indigenous languages. “If this book was in any of the African languages instead of English, it would be almost impossible to find a publisher” states the author. Although it is true that the local literary landscape is tough for writers to publish in their home languages due to lack of vastly available publishers, distribution and access of indigenous books, the author falls short of recommending alternative solutions.

Basically, the author gives a stern claim that there are no attempts to promote reading and writing in home languages in South Africa. In so doing fails to acknowledge initiatives committed to promoting indigenous languages such as Puku Books, Via Afrika who established WritePublishRead in 2017, Indigenous Languages Publishing Programme and many other community based groups.

Therefore this shows that the author’s claims may be contradictory and detached to the current state of affairs in the country. The overall tone of the book is filled with generalizations, assumptions and unsupported arguments thus somehow giving a distorted picture that there are no initiatives being implemented in South Africa to try to deal with the various social ills from a human-centric point of view that could be aligned with BC values. Thereby positioning BC as the much awaited “savior” in resolving the country’s ongoing issues.

The rhetoric tone further makes the book somewhat of a political manifesto advocating a noble ideology to a desponded electorate.

CONCLUSION

The author tries his best to sing from the same tongue-lashing hymn book, Capitalist Nigger- The Road to Success, a Spider-Web Doctrine by Chika Onyeani (2000).

On weather Mangena hits the right notes with readers it remains to be seen (and heard). In conclusion, We Can Fix Ourselves is a worthy read to a new audience unfamiliar with Black Consciousness or African Humanism philosophies. To those familiar it is a timely reminder to plant love, kindness and humility at the center of leadership in creating a better society.