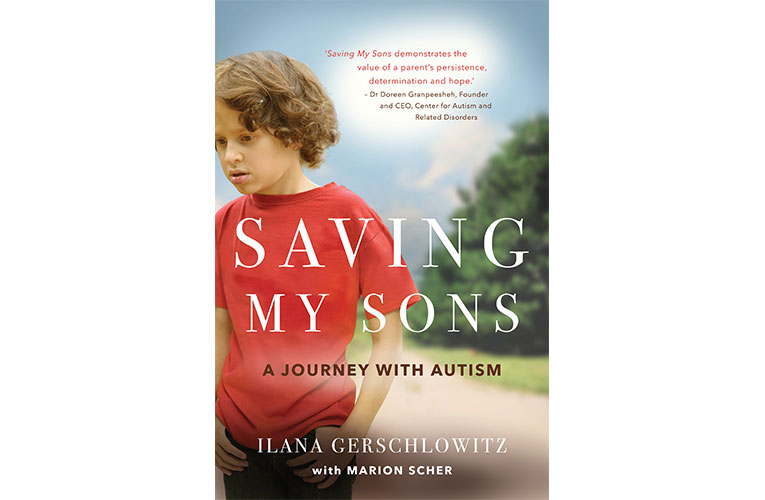

The book tells of a family’s battle with Autism and triumph

By Ilana Gerschlowitz with Marion Scher

Our firstborn’s arrival We couldn’t wait for the day of David’s birth. Since I was having a Caesarean, we arrived at the clinic on the date decided on by my gynaecologist – 24 June 2002. I remember standing and looking down at the empty crib in the maternity ward, waiting full of hope and excitement to see my baby finally lying there. And to take my first steps into motherhood …

I remember the Caesarean and the excitement of having a baby as if it were yesterday. On the first night I was so elated that I had a son I couldn’t sleep. It was the most special moment of my life. I bonded with him instantly, played with his little fingers and experienced love as I never had before. We couldn’t wait to take our baby home and begin our life together as a family. On the first night at home, all the usual cares arose: how to sterilise the bottle; whether my house was hygienic enough; how to bath and burp him. I battled with breastfeeding as David wouldn’t latch. As with any firstborn, things were a bit topsy-turvy, but I was happy, grateful and well pleased with life. Our dream baby: June 2002–February 2004 I was the exemplary mother, taking David for his BCG, Polio, DTP, Haemophilus influenzae type b, Hepatitis B and MMR vaccinations on the dot at the prescribed intervals.

David was the perfect baby: he smiled, lifted his head, rolled over, sat up without support, crawled, pulled himself up into a standing position and walked at all the normal milestones. He played peek-a-boo and hide-and seek, and loved his little blue scooter. He looked at us, and rewarded me with a huge smile when I tickled him. Apart from a little reflux at seven months, life was idyllic for the first ten months.

From ten months, he suffered from recurring ear infections that the ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist treated with antibiotics. Pretty normal for a baby, we thought. At about 11 months, diarrhea and a high fever that lasted for seven days landed David in hospital.

The paediatrician struggled for almost two hours to find a vein in which to insert the intravenous (IV) drip … and David fought and screamed the entire time. We felt that this incident had really affected him adversely. When we went home, however, we suddenly noticed that our son didn’t want to look at us anymore. This was frightening. He also showed no interest in playing our usual games of peek-a-boo. The laughs, smiles or reactions that ‘normal’ babies his age use to communicate were gone; the sparkle in his eyes had dimmed … and the countless trips to doctors, specialists and therapists began. Life as we knew it – and as I’d so carefully planned it – was over. No parent knows what the future has in store when they excitedly hold their newborn in their arms. For us the future would unfold like a horror story with shocks at every turn – but at the beginning we still hadn’t opened the book. Raising children presents challenges for every parent, but raising David took intense courage. In those early years, it was a one-way street of constant giving without receiving anything in return.

Therapists, specialists and increasing unease David was 18 months old when I began my search for answers. He was unresponsive and had stopped developing. I’ll never forget my first visit to an occupational therapist, one well known for her expertise with babies.

David walked into her therapy room and ran around in circles. He wouldn’t touch any equipment she presented him with and made no eye contact with her. She didn’t speak to David and instead tried to lure him with the usual baby toys, but without success. At the end of the appointment she told me there was certainly cause for concern, briefly mentioned the word ‘autism’, then told me she wasn’t authorised to make a diagnosis. She mentioned that most kids looked at her fleetingly at least, but that David had made no eye contact at all. She expressed the opinion that he was too young for a diagnosis and that we should come back in a few months’ time.

I left the therapy room with an uneasy feeling and a heavy heart. By the time I got home, I was in tears and fear had set in. Looking back, I wish she’d confirmed the red flags of autism right then. If we had received an official diagnosis around that time, David could have started treatment much earlier and might even have recovered.

We know now that early intervention is key. In my heart, I simply knew that David wouldn’t ‘grow out of it’. I’d read about the developmental milestones; and knew they were there for a reason. I felt very uneasy that David wasn’t reaching them. I wasn’t prepared to lose valuable time and I wasn’t going to wait months to secure an appointment in search of a diagnosis. I was looking for confirmation of my worst fears, because I felt that the sooner I identified the problem, the better were my chances of improving our lives. At that stage of our journey, though, there was always someone to reassure us – incorrectly – that he was ‘a late starter and he’d soon catch up’. It couldn’t be autism, right? David looked so normal … Had we listened to this advice, it may have been another three or four years before we looked for help. We’d have lost many years of crucial intervention and development had we not taken action immediately upon discovering that David was not developing on time.

The next appointment was with the paediatrician. I described David’s bowel movements and his delayed development. The paediatrician diagnosed him with toddler’s diarrhea.

He assured me the frequent bowel movements were insignificant and would pass. Once again, I was dismissed without progress. We went on to consult a speech therapist trained in neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT), whom we had been assured was the best local practitioner in the field of delayed language acquisition. David cried and screamed for most of the consultation, refused to co-operate with her and wouldn’t imitate what she was doing. In a last attempt to escape the demands she placed on him, he threw himself on the floor, distressed and with his hands flapping. It crossed my mind that if she couldn’t manage his behaviour, she’d likely not succeed with the therapy or its ultimate goal of speech.

David and I then flew to Bloemfontein to consult the top neurologistin South Africa. I remember sitting on the plane with David and looking through the window at the clouds, hoping I’d have answers on my journey home. Sadly, this trip didn’t bring answers or the solution I’d so desperately hoped for. After seeing us for about an hour, the neurologist told me to put David onto Risperdal (a psychiatric medication) for his hyperactivity. ‘Push the dose,’ he said, ‘you can go up to 1 mg of Risperdal.’ My gut instinct told me this wasn’t the answer, and I was right. Risperdal did nothing to calm David. It just made him tired. Looking back, we realised we were giving him psychiatric medication when he was in fact a medically ill child.

The neurologist mentioned in passing that we should try to get his continuous bowel movements under control. He didn’t, however, make the gut–brain connection or even mention autism when the signs were so glaring.

No help anywhere ‘Take him for play therapy to a psychologist specialising in children who are not social,’ the voice on the other end of the phone advised. I politely agreed with my concerned friend, who was offering advice to take David for play therapy. In our quest to do everything possible, we also took David to a psychologist who tried to engage him. He, too, was unsuccessful. Everyone was too afraid to mention that dreaded word – ‘autism’.

All the professionals from whom we sought help were unable to offer either an official diagnosis or a lasting remedy. David regressed rapidly. He’d lost his speech and the side effects of the medication caused worse problems.

Behaviourally, he only made eye contact fleetingly; didn’t have any imaginative or constructive play; and didn’t imitate us by clapping his hands or waving. I was beside myself. We could see David’s regression but could do nothing to stop it. It was like a runaway train. After all these negative experiences, we had nothing to show. Hopelessness set in and the future seemed bleak. One relation came up with what he felt was the solution. Put David in a home and forget about him …

.Extract from SAVING MY SONS A Journey with Autism by Ilana Gerschlowitz with Marion Scher. Published by Bookstorm. Available in all good bookstores and online. Recommended Retail Price:R320.00