Herri journal’s content is fresh covering politics, arts, culture and society

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

It is quite interesting to observe that some of the most interesting publications in the history of journals happen to be underfunded, under sponsored and are created by visionaries whose motivation is not really financial gains, but to push certain ideas that are worth hearing but are absent or not featured in the mainstream commercial media. These individuals who start such publications one could say are actually idealists who derive immense pleasure and satisfaction to see their ideas manifest themselves into something tangible, something that leaves a mark and something that gets conversations going on at different levels.

And yes sometimes there are financial rewards, but a lot of times there are none but the satisfaction that comes with other successes not related to finance are just good enough for such mavericks, for example winning awards or at times having one or two of their stories picked up by the big players in the industry, the mainstream, in other words beating the big guys at their game.

One such publication started with a shoe string budget, but which is fast consolidating itself in the digital publishing space is Herri. Using freelance contributors from diverse backgrounds including, but not limited to academia, media, independent writers, opinion makers and the broader commentariat, sector, Herri’s content is fresh, thought provoking and quite insightful, cutting across, arts, culture, politics and society.

Edited by Aryan Kaganof, its package of editorial mix is quite diverse. The case in point is its latest issue.

Of all universities that I attended, Stellenbosch’s mood was the coldest. In that university, a black student is made to feel that he/she is visitor. Of all the communities that I visited, Stellenbosch was the most racist. The Stellenbosch community and its racial vibe requires some research. Anyway, this peeing white boy was born post apartheid. He has no experience of the “sweetness” of the segregated system, though he continues to enjoy its privileges today. Where does he get his racist character?, writes DJO Bankuna in the latest issue about the recent urinating incident and the racial row that followed.

In this article aptly titled Pissing On The Rainbow Nation he continues his tirade.

“Legislated apartheid is dead, but the apartheid socioeconomic structure is alive and well. Wealthy white families continue to exist in isolation in the wine farms, the abhorrent gated communities, and surbubs of Sandton, etc. Their circle of interaction is exclusive to white people. Their only interaction with a black person is with their workers. Wealthy white people are completely insulated from the broader societal South African experience. The same is true about the overwhelming majority of blacks and their families. Their lives continue to be isolated in townships and squatter camps. Their only interaction with a white person is at work, as a worker, and at the mall. No shared life, no shared hopes, no shared trials/tribulations. It is impossible to create a rainbow without a shared lived experience of what it means to be a South African.”:

Some of the article are quite academic, for example Glenn Holtztman’s titled Music Department in South Africa as a Mirror of Racial Tension and a Transformative Struggle: Critical Ethnographic Perspective.

“”The primary argument of this essay is that the normativity of Whiteness in South African music departments renders Black South African musicians and academics as non-normative, and makes it difficult to achieve transformation that privileges the normativity of Blackness in the department, or drive decolonisation. I write from a position of Blackness, as experienced under apartheid and also in the present, as a Black student during the 2000s and a Black lecturer in three South African music departments. The accounts offered on this page; of several of my own experiences of racialisation, discrimination and exclusion while situated in South African music departments, serve as entry point into investigating broader issues of transformation at South African universities,” Holtztyman writes.

”JOHNNY MBIZO DYANI, one of the most accomplished bassists to have come out of South Africa, died on stage at the Berlin Festival on Friday, 24th October 1986. He was born in East London on November 30, 1945[1]. His instrument was a piano, but he was later attracted to the bass which, to him, has the deep notes resonant of the folk choirs back home. In this profile, I trace some of the influences that made him a great artist.

Freedom was the lodestar of Johnny Dyani’s life. He sought it for both his country and his people. He sought it also in his chosen career — in music.

Johnny Mbizo Dyani’s path to a career in music began like that of many others in the bustling townships of South Africa’s urban areas. He was fortunate in one singular respect — an early exposure to some of the leading musicians from the black community. His home, in East London, had for years been a regular stop-over for musicians on the road. He thus rubbed shoulders with seasoned professionals from an early age. Much of their skill was passed on to the impressionable youth. He displayed a precocious interest in the double bass, first picking up tips from itinerant musicians, then beginning to play with his peer group. The formative influence at this point in his life was Tete Mbambisa, an exceptional pianist, composer and arranger. It was as part of a quintet of singer/dancers, led by Mbambisa, that Johnny made his stage debut. Throughout his musical career singing remained one of his great passions.

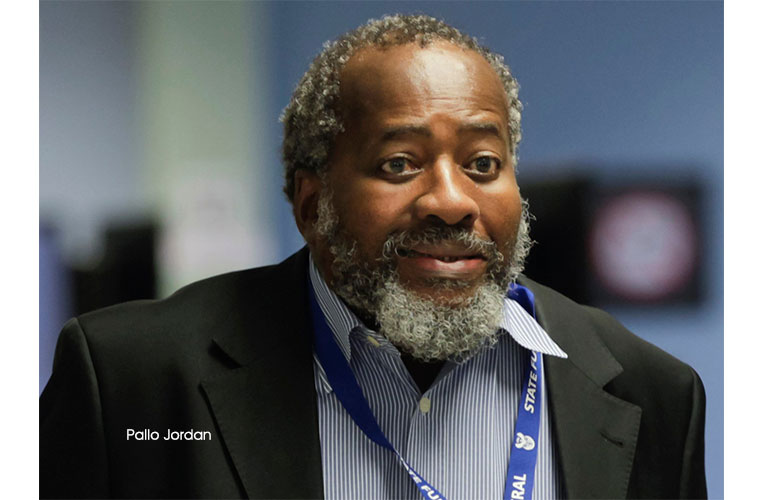

Touring the coastal cities along the garden route, the quintet made a big hit with their spirited and highly original renditions of such American jazz standards as A String of Pearls, Three Coins in the Fountain, My Sugar is so Refined, This Can’t be Love; and others. It is a lasting testament to both his talent and perseverance that from these small beginnings, in non-amplified, dingy, drafty dance-halls, that he grew into a much sought-after international talent,”writes former Minister of Arts and Culture and now a retired politician Pallo Jordan.

The article is well written, well-presented and well researched by someone who not only lived during the life and times of the late musician, but a friend too. The article traces the genesis of the late musician in the Eastern Cape right up to his exile years on London where both the right and the late musician found themselves living.

You can read more articles about the late musician, including listening to interviews on herri.org.za