A Johannesburg exhibition sparks robust discussion about space and role of women in contemporary South Africa

The exhibition features the works of Khubu Zulu, Senzeni Marasela and Heleni Sebidi among others. At its opening at Elis Art House on Saturday, it featured author Barbra Masekela, Sebidi, Marasela and Zulu in a robust panel discussio0n. The exhibition pays tribute to the Women’s March of 1956 to the Union Buildings.

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

When I could not go to this exhibition preview at Elis House in Doorfontein the previous week, I was disappointed with myself. But when another chance beckoned to attend the opening proper of this exhibition featuring women artists commemorating the march by South African women to the Union Buildings in Pretoria in 1956, I was elated. Felt redeemed actually.

And when I found two of the participating artists Khubu Zulu and Senzeni Marasela at the entrance of Khubu’s Studio on the 5th floor of Elis Art House, which doubled for the day as the exhibition space, I got even more excited.

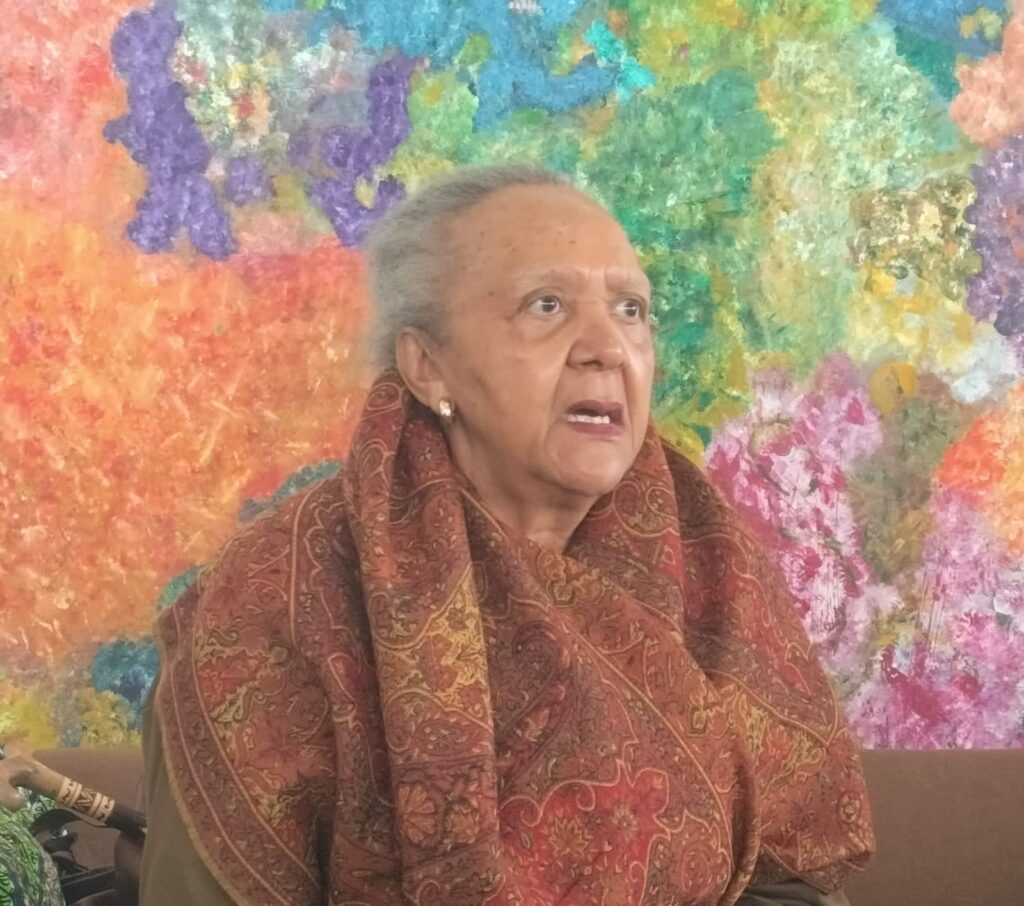

It was though seeing author, political activist and former diplomat Barbara Masekela and renowned South African artist Heleni Sebidi that really got me thinking, well, I am at the right space and the moment was just perfect. The two ladies when I arrived were in an intimate discussion and one could tell that they were exchanging words of wisdom gained over many years of their individual experiences as artists, activists and politicians. For in South Africa of the past, it seems one needed to be super-talented in more than one way to survive.

The oppressed played multiple roles during the dark years of apartheid, just to get by and survive the suffocating system. There was not much of a choice for that generation. That probably explains why those that marched to the Union Buildings, the theme of this exhibition and a tribute to them, came from different backgrounds –some from the professions in the city, black and white, while others were simply rural mothers struggling to raise their children under the burden of apartheid. But when it came to that now famous march commemorated in various ways in South Africa, both officially and through individual endeavours such as this exhibition – they were all united by the issue of the pass laws that black people were required to carry by law.

On Saturday, August, 19, 2023, as the discussion started at Elis Art House, I was part of the audience. Small as it was, there were among the audience men and women of substance, who took time from whatever else they were to do or attend to, to hear words of wisdom and admire of course brilliant works of art on the walls by the participating artists. As an example of the type of audience that came there, there was a retired professor of literature, a veteran journalist, an architect-turned artist, and of course yours truly, and the list goes on. I am sure you get the drift.

After a shoirt walkabout of the exhibition, (Khubu with Marasela were instrumental in making sure that this exhibition happens both as participating artists and architects of the event, and encouragingly roping in young really talented women artists), it was time to sit down, and listen to these wise women artists.

The panel anchored by Khubu, with Masekela, Sebidi and Marasela as fellow discussants, was an illuminating experience as one got insights into the minds and experiences of the women artists, including their lives during apartheid (especially when it comes to Masekela and Sebidi), as well as life in post-apartheid South Africa. bThe discussion was quite vibrant.

When prompted by Khubu’s talk about how she reacted to apartheid oppression as an oppressed black woman, Masekela shot straight to the point.

“I do not get defined by my reaction to oppression. I get defined by my resistance to oppression. ”With that bold statement, Masekela set the tone for what turned out to be a lively and honest discussion during the opening of this exhibition.

She went further to explain that these days she finds it problematic for people to look at their lives as individuals, without connecting to who they became because of the p-eople that surrounded them as they grew up.

“We are actually a product of many people in our lives, in our environment. Take my case. I would be happy if I could be able to say I come from Eastern Cape or KwaZulu-Natal, and I have a place I can point out there and say I come from here. The reality is I come from an urban area, Witbank, and the only reference to a sense of place are the factories, the coal mines. I was brought up by a grandmother whose people were uprooted from the local farms by white people. She brew liquor to bring us up and to become an independent woman,” said Masekela. She also added that at that time, there was no such terms as feminism, in her generation and even the generation of her parents or grandparents.

Sebidi, in her usual witty manner explained that the rural area she grew up in (outside Pretoria), the men who left and worked in the city often came back with nothing due to the slave wages they got from their white bosses.

“We witnessed these people working in the city coming back home during holidays with nothing. Often they would leave the rural areas with something. It is then that I learned about the conditions under which they worked and lived and I became curious. And when I left the rural areas myself for the city, I had already learned about the harshness of the city from and for me it to was to learn communication in the city, nothing else. When I left the rural areas in 1958, I was a free person, and independent because the rural areas gave you that privilege, and not the city,”Sebidi said.

But it was that independence of mind and her attitude of freedom that later got her into trouble working as a domestic worker for various employers in Johannesburg.

“I got into serious trouble for that. In fact I never worked for one employer for long as I would change from one employer to the next as a domestic worker until I worked for one Germany family who treated me differently and with respect.

Often with the previous employers I could get accused of walking in their house as if I owned the house. In the streets, I got accused of walking like a white person. It got so bad that one white guy, a neighbour of my employers in Honeydew bought a knife and hired someone to kill me in the streets simply because they accused me of walking like a white person, and that I thought I was white,” Sebidi said amid loud laughter in the audience.

That was then, but the discovery of art, has today propelled her to be one of the most significant black female visual voice of her generation, among which you will find XiTsonga sculptor Noria Mabasa and Ndebele painter Esther Mahlangu.

Marasela who early this year made global news when she won a major global prize said to be worth 70 000 Euros, told of the genesis of her art practice, which highlights the struggle of women in a country which is defined by both immigration and migration.

For years the artists has created alter egos that have become impactful and central to her art practice. The art establishment is now starting to notice her and yet the global recognition.

“My art practice has always been informed by my own mother’s struggles especially with a husband working in Johannesburg while she had to raise us on a farm in the Eastern Cape,” Marasela said.

Marasela who works in textile to tell the stories of women and their struggle in the city. Her art practice over the years has shifted from being a personal story of her mother to a story that encompasses the struggles of women in general struggling for recognition and opportunities in a city where patriarchy is still the social fabric.

“Today we talk about the Zama Zamas-illegal minors digging for gold in abandoned mines. But what people are not probably aware of is the fact that near these illegal mining places, there is always an informal settlement where mainly women eke out a living trading stuff. These places are not only now occupied by black South Africans, but also women from the continent. This is the reality of South Africa today –attracting migrants, just in the same way it has done for 100 years because of the discovery of gold.