After two months of attracting visitors artist Thonton Kabeya’s exhibition to close with a performance art event at Wits Art Museum

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

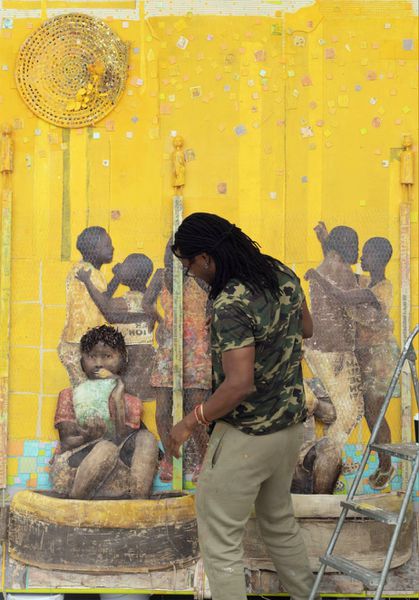

Thonton Kabeya has just achieved what many of his practising generation are yet to do, which is to have a solo museum exhibition, all of the more than 60 art pieces belonging to him, his own art he collected in the past 10 years of art practice in Johannesburg. His exhibition at Wits Art Museum in Braamfontein, Johannesburg has in the past two months been attracting collectors, art lovers, students and fellow artists to view and admire his labour of love and art practice. The exhibition is eventually coming down on Saturday, 14 October 2023. There will be a big closing party that will see the artist perform with the Johannesburg Opera, interpreting and capturing the emotions of some of the art pieces displayed on the first floor of WAM. The performance is at 2pm.

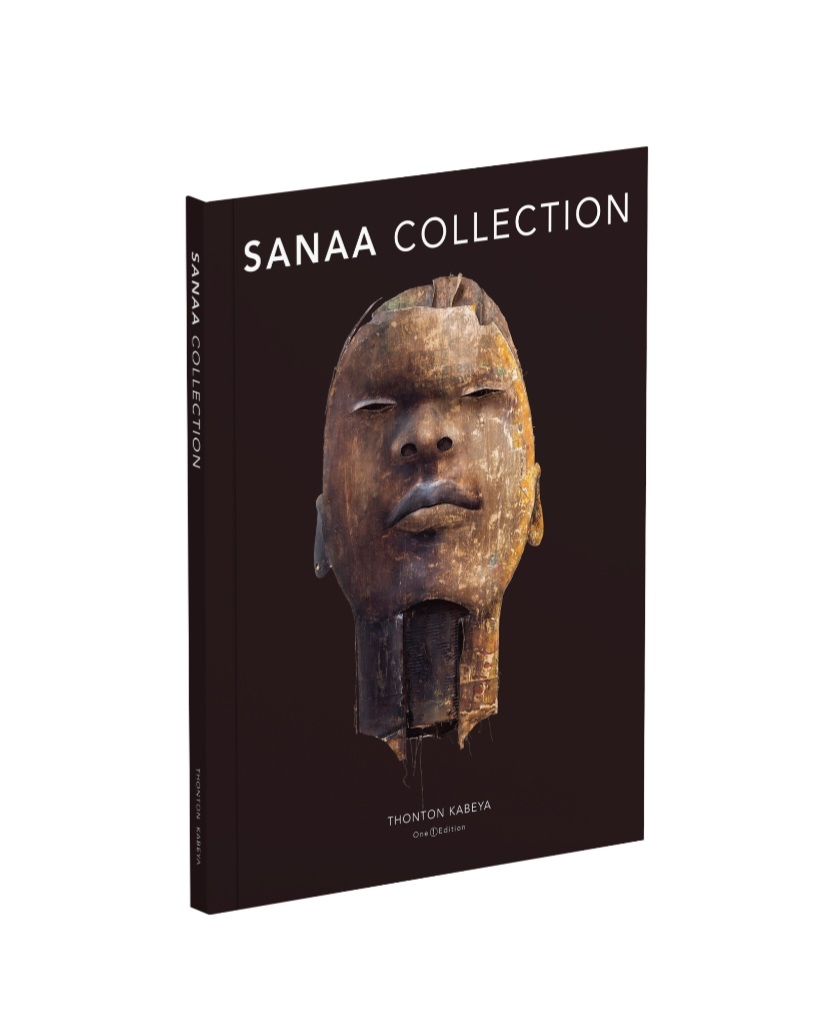

“The exhibition has been well received and some of the people who viewed the exhibition have been sending me messages on social media, telling me that they had gone to see the exhibition for the fifth time. It has been a great experience, especially having a Q&A with sometimes 40 to 100 students at a time,” he reflected on the success of the exhibition speaking to CITYLIFE/ARTS at a Melville Café on Thursday, October 12, 2023. The exhibition was accompanied by an art book, which is currently on sale at Wits Art Museum. The book will be on sale during the closing party.

This is the second time that CITYLIFE/ARTS has held an exclusive interview with the artist regarding the exhibition in two months. In the first interview, which was held in his studio, which till now we had not published, is published below, explaining the rationale over the holding of the exhibition titled Introspect.

Kabala’s quest to collect African art for the benefit of future generations of Africans

A conversation around the issue of returning or restitution in relation to African artefacts stolen by colonial powers during the colonisation of Africa continues to be discussed on the continent particularly in academic, intellectual, artistic and civil society circles.

During colonialism, representatives of colonial powers on the continent, stole many art works from several countries in which colonialism took place. Some of these art works were used in sacred ceremonies and were not for public display. The actions of the representatives of colonial powers on the continent, therefore, did not only steal the art objects, but also demeaned scared cultural practices of African societies by taking the art objects and displaying them in their museums for the gaze of the European public.

Two prominent examples of stolen art objects that are kept and housed in European museums are the Benin Sculptures, kept in the British Museum and German ethnographic museums, and the Congolese artefacts that are kept in the Africa Museum in Belgium. These are said to number 84 000 artefacts. This number excludes other works of art from other African countries stolen during colonialism that are also held by that museum.

However in recent years, voices have emerged on the African continent and elsewhere, demanding that these stolen art objects be either returned to their rightful owners, or some sort of reparation be undertaken by the European countries that have these artefacts in their museums. The voices became louder especially during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2021. Some of the European countries are starting to respond to these demands, if not in practice, symbolically.

“Belgium took a small but symbolic step toward addressing its colonial past on Thursday, with Prime Minister Alexander De Croo handing over to the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo an inventory of 84,000 Congolese artefacts dating from the colonialism,” Politico Europe website on its February 17, 2022, edition reports.

This report is in reference to Belgium’s Africa Museum, which was established in 1898 on the outskirts of Brussels, is home to some 120,000 items from Africa, mostly from the Congo when the Central African country was a colony of Belgium, the reports further states.

This development followed King Philippe’s expression of his “regret” for the “acts of violence and cruelty” that were committed in the Congo under Belgian rule, the move is an olive branch between Brussels and Kinshasa, the report explained.

But handing over the inventory doesn’t mean that Belgium’s loot will quickly return to its home country, or to the Congolese population, the Politico report further states.

On June 29, 2022, it was also reported that Germany was going to return looted African artefacts, including over 1000 Benin Bronzes, and these are the collection of metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin, in what is now south western Nigeria. These too were looted during colonial times. The bronzes that have found their way into 20 museums across Germany were mostly taken by British forces when they conquered, burned, and looted the city of Benin in 1897.

“The invaluable Benin Bronzes will be restituted to Nigeria after German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Commissioner for Culture and the Media Claudia Roth signed a memorandum of understanding with their Nigerian counterparts in Berlin on Friday that clears the way for the transfer of ownership rights,” reported Germany media platform,” the report says.

“In February (2022), France returned 26 bronzes to Nigeria that were stolen in 1892 by French colonial forces from the former Dahomey kingdom, in the south of modern-day Benin.

For many decades, museums and political leaders in Germany — which was the third-biggest colonial power after Britain and France until World War One — had avoided talks on concrete agreements for transfers or even restitution. But that has changed since 2021, when representatives of the German and Nigerian governments, and museums, announced the decision to transfer ownership”, the report continued.

Conversation with Thonton Kabeya

Congolese born, South African based artist, Thonton Kabeya, who came to South Africa 10 years ago, and has been working as an artist since then, argues that although the theft of African artists’ works -during colonial times was wrong, in post-colonial Africa art works created by African artists continue to flow to Europe. These modern day works of African creativity find their way in European museums for the eyes and intellectual stimulation of Europeans. The only difference is that in postcolonial Africa, the movement of African art to Europe is voluntary. It is the African artists themselves who sell these art works to the European art market. But the effect is the same as Europe continues to enjoy their hold on African art objects disproportionately. This is the gist of Kabeya’s argument and how he personally tries to mitigate against that loss.

“The only difference therefore, is that in colonial times, the art objects were stolen and looted from Africa. But now we are doing the same thing voluntarily, and that is handing over the art works to European museums,” he argues.

It is for this reason that Kabeya made a decision that he was going to collect his own art works, and not sell everything that he creates. He now has an impressive collection of his own works and he hopes that this will inspire other African artists to do the same. This collection, which he has titled

Thonton Kabeya had a conversation with arts journalist Edward Tsumele about his practice of collecting his own art works.

Edward Tsumele (ET): What inspires you to build a collection of your artworks?

Thonton Kabeya (TK): Firstly, I did not know I was building a collection because I started by keeping my own works from galleries or art dealers who felt they were expensive. But I knew the value of such artworks and always believed that someday, there would be someone who would be prepared to pay for them – and also because of a number of other factors. Among these is the time I spent working on these pieces.

ET: For how long have you been collecting your artworks?

TK: Unofficially, I started collecting my artworks from the time I started keeping them. They were shown in galleries, but were not for sale for the reasons I have given above.

But officially, it was when I heard the news about the call for the repatriation of African artworks in European museums that had been stolen from Africa centuries ago. That is when I started developing the idea of collecting art with a sense of purpose – you could say I had taken a philosophical stance, I felt I had a purpose to start collecting them.

I then understood that collecting my own artworks was not about those that had not been sold. I found that even before the work left the studio, I was already putting aside ones for my collection – I’ve been doing this for some years now.

ET: Building a collection comes with many responsibilities, even a cost. Can you say what these are?

TK: There is a huge responsibility on the part of the collector. As artists, our role is not just about creating beautiful things. We are part of the gatekeepers of our culture and must have a vision that looks beyond our own lives because the art we are collecting now has to be useful to the generations that come after us.

We need to define what we stand for as artists – and that is having a vision that goes beyond our studio practice. We need to understand the role of art in terms of its social impact, for scientific studies and spiritual purposes, not forgetting the economic side of it.

ET: You are one of those people who believes that African art objects which were stolen during colonialism and are now in European museums for the enjoyment of Europeans and tourists must be returned to Africa. Why do you think that’s important?

TK: Africa is the only place where these artworks are safe. Those works were stolen, there’s no question about that. There is also no need for negotiation. The works must be returned with no conditions by European countries and the museums that hold these artworks.

But on the African side, there must be a condition that the European countries must build the infrastructure to look after such artworks. That is the charge for stealing the work. They have been making money, profits even, in their museums by charging the public for viewing these artworks.

ET: Although the demand for stolen property from those who stole it – in this case African artworks stolen during colonialism – is a noble idea, there is also a reasonable argument by others, including African thinkers, that perhaps a different approach should be adopted as a way of restitution.

For example, they argue that African countries lack the necessary infrastructure to house delicate artworks, such as those African art objects in European museums that are centuries old. They say that European countries have the necessary infrastructure to do this. According to me, these arguments have a degree of validity given the deplorable state of some of the museums on the continent, particularly public museums.

Is it therefore not better to “loan” these artefacts to countries where they pay an annual fee to African countries from which they were looted? This seems like a realistic and practical approach for the vexatious issue of African art objects stolen from Africa during colonialism and now held by European museums. What do you think about this?

TK: As far as I am concerned, the issue of returning artworks stolen from Africa by colonial powers is equivalent to a court case. This is the way I look at it – the suspect, who is the guilty party, has been identified, and so has the victim. The West has stolen these artworks from African countries. Apart from returning the stolen property, they must pay penalties for the theft.

Let me give you a practical example: If you stole my house and rented it out for 100 years, and I get to regain ownership of it after 100 years, in addition to returning the house to me, the rightful owner, you must also pay back all the profits you made by renting it out for the specified period.

What the European countries and their museums with looted African art objects must do is to pay back the profits they made from the artworks by building the infrastructure to look after them in the African countries from where they stole the works. This is of course in addition to returning the artworks. It is as simple as that.

However, I must also add another very important factor. This is that the African countries whose artworks were looted must not make the same mistake as the Europeans. They need to be careful about which artworks to display in their museums once they get them back. These countries need to identify the stolen artworks that are sacred to specific cultures and customs from the region where the artworks were stolen.

Once that has been established, the inventory of such works needs to appease the ancestors by either burying such artworks in the ground or destroying them by burning them. This is because some of the artworks are not for public display because of their sacred, spiritual functions and purposes. There is a need to acknowledge the harm that has been visited on the ancestors by subverting the purposes for which the artworks were created on African soil. That is before they were looted.

ET: Why do you think displaying your collection through this Introspective exhibition is an important step in opening up the conversation about the need to collect art objects by African artists for Africans on the continent?

TK: I hope exhibiting my collection titled “Sanaa”, which means art in Swahili, will inspire other artists or African galleries, art dealers or anyone who wishes the best for the future of this continent. This is one of the steps to start with. Just join the idea and do the same – that is collecting artworks for the benefit of future generations.

In fact, this is essential, especially If we care about future generations. I therefore sincerely hope this exhibition at WAM, (Wits Art Museum) Johannesburg, will be an inspiration for fellow artists and other African collectors to do the same. I hope from the bottom of my heart that It doesn’t matter what the colour of your skin or your gender is

At the moment, I am in the process of establishing a trust that will manage the collection as a legacy. This is not just for the benefit of me or my family, but for Africans in general. The trust must ensure that such works are looked after and can be displayed for the right purposes, such as in public spaces.

But under no circumstances must these works be sold. They are not meant for personal or family benefits, but for the benefit of the public, particularly future generations. The trust will have the responsibility of managing the collection. I am in the process of establishing one, and hopefully other artists will start thinking along the same lines. The truth is, once you are gone, and you leave an art collection with no plans for it, it will be difficult to carry the vision to its destiny.

ET: Finally, where to from here for Thonton Kabeya, the artist?

TK: I want to keep working and keep moving on.