Ending year’s art circuit on high note by visiting Javett Art Centre, a sundowner in Alex

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

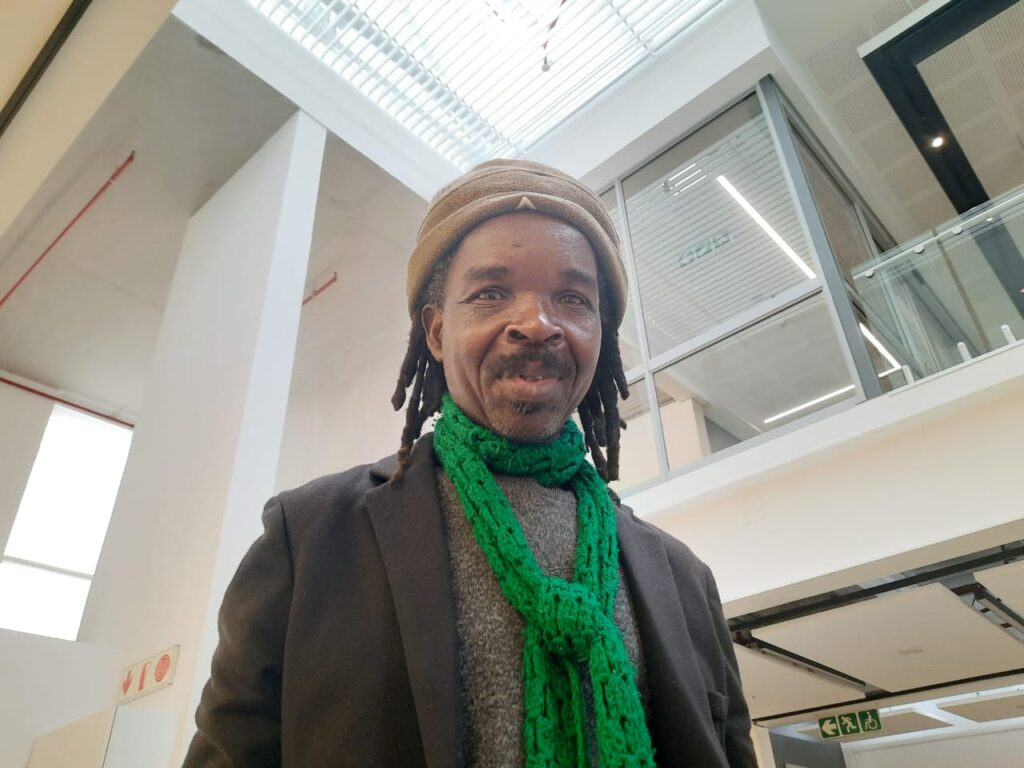

There could not have been a better way of spending the last few days of 2022 than taking a trip to Javett Art Centre at the University of Pretoria. So my team of three hit the road on Thursday, December 28, 2022, taking the N! North from Johannesburg. Once we arrived at our destination, our minds, eys and intellect got engaged with what was on display. We immersed ourselves in the art that is on display in various exhibitions that are currently on there.

One thing about the Javett Art Centre at the University of Pretoria that distinguishes itself from other museums is the fact that once you are inside the building that is attached to the University of Pretoria Hatfield Main Campus, but conveniently accessible to the public from the street, you immediately notice that there is ample space in the various exhibition halls. This al lows for creativity in how curators choose to display the art works.

One thing that is stifling in some museum displays is that art objects tend to be placed so close to each other to the extent that the place becomes throttling, giving a sense of over-crowdedness and not allowing the objects to breathe. After all one does not want a situation whereby one feels as If the objects have just been dumped, stored for safe keeping., and not displayed for public viewing and appreciation The exhibitions currently concurrently running at this museum are well curated, allowing for decent engagement with a viewer.

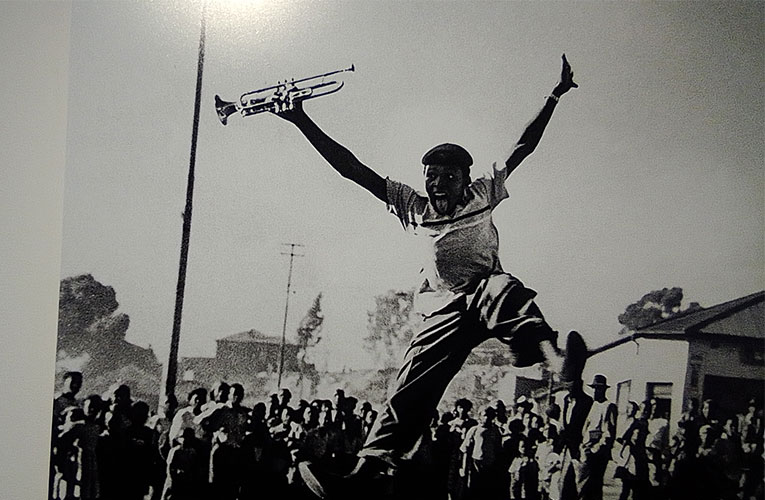

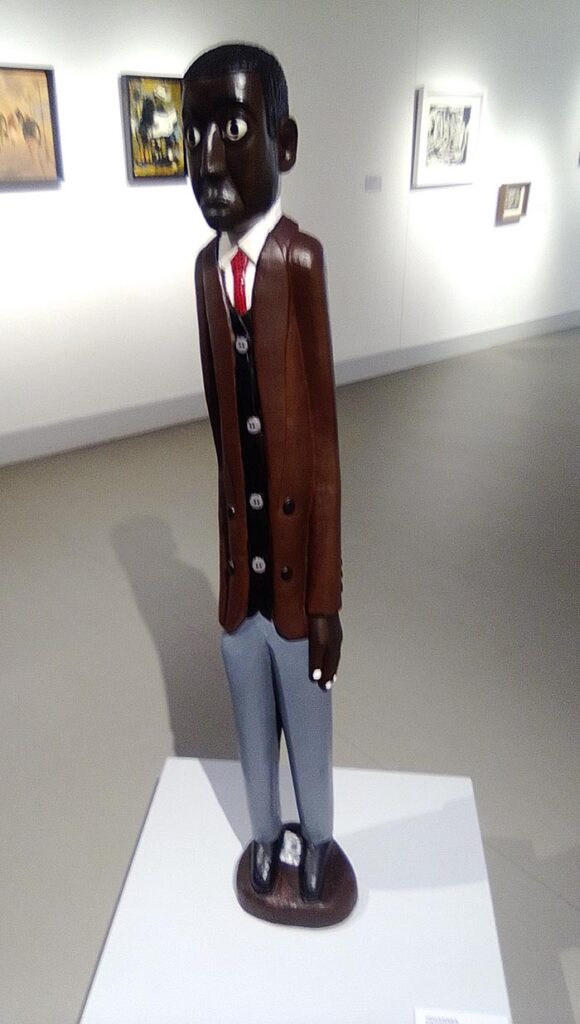

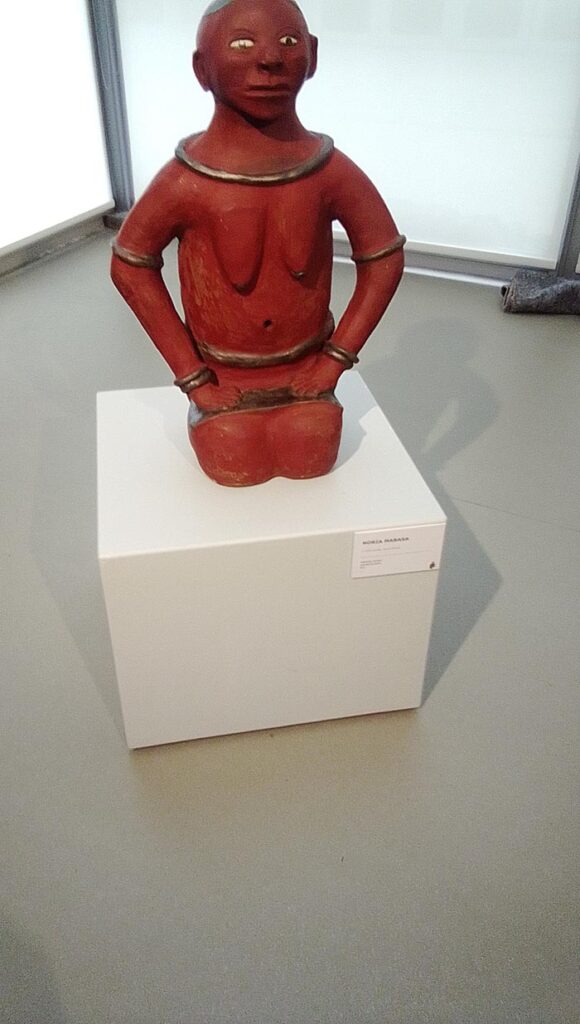

I particularly liked the Yakhali-inkomo exhibition, which is a display of art objects in various media created by black South African artists from the 20th century right to the contemporary times. And these works that among other media are in painting, photography, drawing, sculpture, wire, fabric and video installations. Among others, tell the story of South Africa’s past and its present, as well as giving a sense to a viewer of where the country may be headed going into the future.

Various black artists’ works are part of this interesting exhibition to view. In the process one gets to learn not only about South Africa’s art history, but its complicated past of racial segregation and oppression too. One can even get provoked by some works too.,

For example a picture of a group of naked black men, who look helpless in the face of torment, with their hands up and their naked selves lined against the wall, taken by the late South African photographer Ernest Cole, remind us of the humiliation of black workers during apartheid. Those looking for work were first stripped naked publicly in the name of making sure that they were in good health to work in the mines and farms.

One can imagine what must have been going on in the minds of these people humiliated this way by the so called health inspectors. Their ego must have been deflate. Their prided decimated. Their sense of dignity stripped from them. Their vulnerability as oppressed people with no vote, not rights amplified by this act of stripping them of their sense of worth as fathers, brothers and uncles of other people.. This was cruelty not medical science.

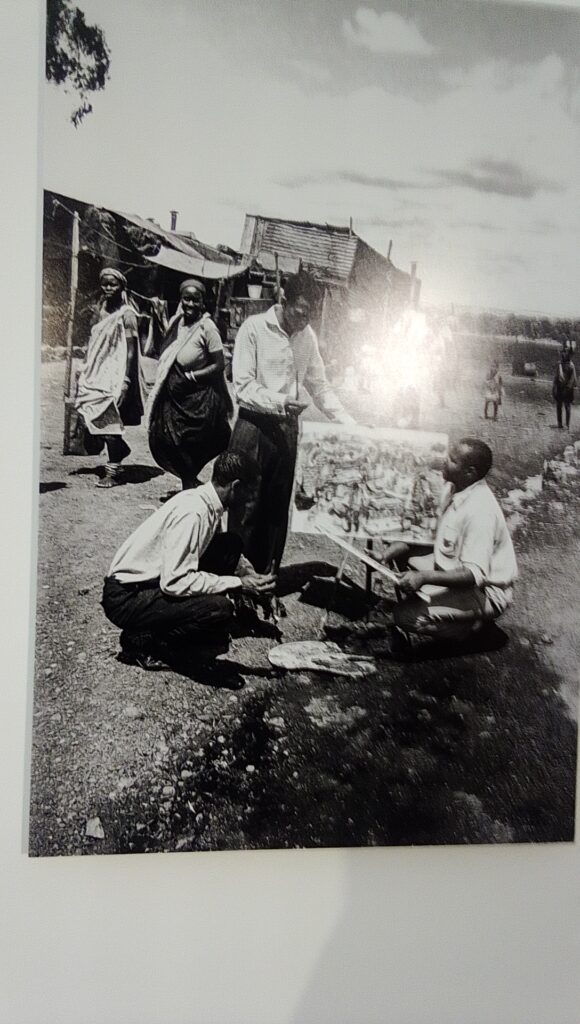

One other piece, a photograph of artists Ephraim Ngakane, Sydney Kumalo and another artist whose name has just slipped off my mind, captured on film practising their art in the streets of Johannesburg in the 60s, just goes to remind us of how black artists struggled to practice their craft. Whereas their white counterparts of the time probably had better spaces from which to work from, such as studios, these had to make do with the streets as their studios. This picture was taken by the late word renowned South African photographer Alf Kumalo.

I also got a chance to watch and listen to a video installation of the late legendary South African singer Miriam Makeba speaking about how as artists at the time, she and others of her generation did not have the luxury of singing about love. Instead they had to compose songs that dealt with the condition that black people found themselves in during that time.

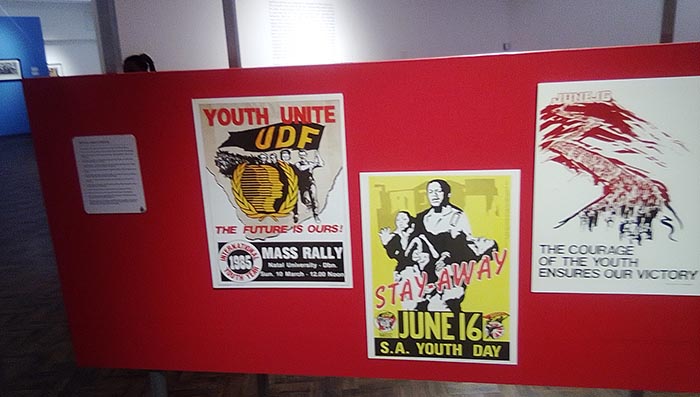

Essentially Yakhal’Inkomo and its program explore how Black South African visual artists, musicians, poets, theatre makers, filmmakers and writers forged acts of creative defiance during the most tumultuous times under apartheid (1960s to late 1990s). Working across media, artists not only recorded their pain and trauma, they redefined and celebrated their identity against the cultural imposition of the state.

While the voices and actions of many of these artists were limited by censorship and suppression, their contributions were instrumental in keeping Black culture alive and resilient during the struggle years. The title Yakhal’ Inkomo is derived from a 1968 jazz recording by the saxophonist and jazz composer Winston Mankunku Ngozi. Translated as “the bellowing bull”, it refers to the bull’s fundamental role in African life, symbolizing spiritual passage, awakening and resilience as well as material wealth, strength, collectivity and community.

Ngozi’s anthem delves into the Black psyche and conjures up feelings of deep remorse, anguish and anger. But it is also a testament to the strength and resilience of creativity in the face of grief and dispossession. As a metaphor for this exhibition, we understand the bull’s cry as an awakening that unified Black people to confront and resist oppression Drawn primarily from the Bongi Dhlomo Collection, the artworks included in this exhibition explore the complexity of the Black experience of urbanization, estrangement, displacement, spirituality, and the texture of ordinary life.

They capture seminal moments in the history of people’s defiance of state oppression. Recovering dialogues between Black artists across genres and media, the exhibition traces decades of exchange that corresponded to the growing restlessness and active resistance of the Black community. These works provide an opportunity to recover and acknowledge this past, and to envision future possibilities of mobilizing its power in the present. In other words, the exhibition takes ownership of this history and explores what it means to be Black in South Africa today. Yakhal’Inkomo is guest curated by Tumelo Mosaka with Sipho Mndanda as Co-Curator and Phumzile Twala as Research and Education Coordinator

However to conclude that the collection at Javett Art Centre in the main is only about the investigation of the volatility and vulnerability of black life during apartheid and therefore evoke sadness in a viewer, would be missing the point entirely. Several collections at this centre speak to different themes either as permanent exhibitions or periodic exhibitions curated by different curators and scholars.

For example, there is a section dedicated to interdisciplinary collaborations among African artists and scholars from across the African continent. This is where new ideas are tried and tested in a safe space that not only allows for new thinking about art practice to emerge, but even failure to happen. This last point is as equally important because If artists are not allowed to try new ideas, taking a risk in the process, the possibility of new breakthroughs with regards to new art practice evolving and getting discovered becomes non-existent.

One other thing that will uplift your spirits in the Yakhali’Inkomo section is the fact that you will be greeted by jazz music accompanying this exhibition. This is obviously meant to jell well with the theme of the exhibition, derived from the South African jazz saxophonist Mankunku Ngozi’s composition. These soothing jazz tunes that are constantly playing in the background by various jazz artists assist in dealing with some of the difficult art objects that confront you from time to time in this exhibition as you walk around. At one stage, it felt like I was at a jazz club, listening to these soothing jazz tunes.

The highlight of my team’s tour of the Javett Art Centre was a visit to the section that has gold art projects from different parts of the African continent, including some pieces from Benin. I liked particularly a golden sculpture of a pangolin from Benin. However what I liked most is the famous sculptural work of the golden rhino, part of the Mapungubwe Collection at the Javett Art Centre. I found myself fixated on that rhino. It was a surreal moment. It felt spiritual. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that it is too close home as my ancestors hail from that part of the world. Mapungubwe is an ancient African Kingdom established at Mapungubwe Hill between 1200 and 1290 AD

Finally when one of our team members suggested that the adventure must end by a sundowner in Alexandra Township on our way back where we were to be joined by three more team members, I was quick to agree. Anyway, after viewing such intellectually stimulating and yet challenging art displays there is nothing that beats a good drink and a sumptuous meal in a place called Gentlemen’s in deep Alex. This one fortunately is not that bad even though it was not our first choice.

In fact it turned out to be fine with the team’s taste. (Sorry Romain we could not find a place open that served a Kota that you craved for). We eventually found this one after trying a number of the most well-known and popular watering holes and eateries in the famous township without success. They were all uncharacteristically closed for township establishments. They were all closed for the holidays. Business must have been good this year in Alex.