Law Professor Pens second novel Sins of the Father

By Dire Tladi

IT WAS midday when Siya Mfundo and Gina Setzin arrived in Lubumbashi. The Consul-General, Tshiamo Tlali, was waiting for them at the station. ‘Mohlompehi. Excellency,’ he said, as they met on the tarmac. ‘The Minister was serious when she said she is sending the big guns to close the deal.’ He gave Gina a light kiss on the cheek and offered a firm handshake to Siya. ‘Oh, I am sure if the Minister wanted the big guns, she would have instructed Lindani to come here himself,’ Siya said, extending his hand to receive the handshake. He was not sure that was correct.

The Minister and Lindani Ngcobo were close, but even the Minister must have understood that, on substance, Ngcobo was not an expert in international law. But then again, big guns were never sent for the substance. They were always sent to exert pressure. ‘This way, Excellency.’ Tlali motioned them towards the terminal building. ‘The team is waiting at the Consulate.’ Siya had not seen Tlali for over three years. He noticed that the man had gained a little bit of weight and his skin had darkened. What had not changed was his humorous use of ‘Excellency’ – a title reserved for heads of diplomatic missions – when referring to persons who were not heads of missions. The other thing that had not changed was his rhotacism – the inability to make the ‘r’ sound.

‘We should go there directly,’ Gina Setzin said. ‘We can go to the hotel afterwards, right?’ ‘Yes, ma’am,’ Tlali said. ‘That was the plan, unless the Excellency here wants to rest.’ ‘No, quite right,’ Siya said. ‘Let’s start at the Consulate.’ Tlali took the front passenger seat in the black BMW X5, allowing Siya to sit on the seat diagonal from the driver, the seat reserved for the head of mission. Gina sat next to Siya. A large South African flag fluttered at the gate of the Consulate.

A security guard, who looked Congolese, in Congolese police uniform, pushed open the gate as the BMW slid in. ‘What happened to the South African National Defence Force guys that were here last time?’ Siya asked. ‘Times have changed, chief,’ Tshiamo said. ‘Budget cuts. We tried to get the UN to allow us to use some of our own guys deployed in MONUSCO, but they flatly refused.’ Inside the compound, the BMW parked in the bay marked ‘CG’. Tlali led them inside the house, through the corridors to a living area temporarily converted into a boardroom hung with pictures of the South African President, Deputy President, and Foreign Minister.

Neo Manyi, Deputy Director-General in the Department of Minerals and Energy, and the head of the South African delegation, offered a welcome. ‘We were just talking about the immunity clause,’ he said when the newcomers had settled on the open chairs. ‘The Congolese don’t want it. They say it is a red line.’ ‘But that makes no sense,’ Gina said. ‘It doesn’t matter whether it makes sense, Gina. You are not the Minister of DIRCO,’ Neo Manyi interrupted. ‘Chief,’ he continued in Siya’s direction, ‘Lindani said you were in charge and that you understood the politics.

The Ministers met and they were ad idem that this agreement must be signed during this meeting. You want an end to load-shedding? Let’s close this deal.’ Load-shedding was a policy introduced in South Africa to deal with the inability of the power grid to handle the power demand by implementing scheduled power outages throughout the country.

‘Well, this is a negotiation,’ Siya said. ‘Let’s negotiate. But my experience is that it is unwise to show the other side that you have been instructed to finalise the deal. So let’s negotiate, find options, test their resolve, and then see where we land.’ ‘Fine, but remember, tomorrow at the negotiations, as leader of the delegation, I will decide when I give the floor and when I don’t,’ said Manyi, shifting his stare from Gina to Siya. ‘Fine,’ Siya was cool but firm. ‘Just remember, once this agreement is adopted, my legal opinion will determine whether it can be signed by the President and whether Parliament will ratify it.’ ‘If you don’t play ball, chief, I will just get Lindani to approve this thing,’ Manyi said. ‘You seem to have forgotten the experience of your department with the Russia nuclear deal,’ Siya smiled.

The Russian nuclear deal was a sore point for Neo Manyi’s department. It had been declared unconstitutional by the courts in part because the opinion from Siya’s office had been ignored. ‘Let’s not get into a pissing match,’ said PumzileZondo, the deployee from the ‘farm’ – the South Africa State Security Agency. ‘We are one team. I trust that Siya and Gina will be able to untie all these legal knots for us.’ ‘Besides,’ said Coenraad Meyer, Lindani Ngcobo’s successor as Eskom Head of Legal, ‘the international law issues that Gina and Mr Mfundo are talking about are not the only problem.

The real issue is the bankability of the project. We cannot get the financing from the World Bank or any other financier until the Congolese agree to basic things that will enable the project to be bankable.’ ‘And quite frankly, with the French stirring the pot,’ Pumzile continued, ‘it’s not clear to me how we will jump all these hurdles.’ The French, she added, had offered to assist the Congolese in the negotiations. In previous negotiations, they had reportedly advised the Congolese surreptitiously. For this meeting, it seemed, the façade would be lifted. ‘But what is their game?’ Manyi asked. ‘I don’t understand what the French interest in this matter is.’ ‘They just don’t want us to get the deal,’ Pumzile said. ‘This deal falls through, they offer to invest in the development of the hydro-electrical project on the Congo River, then they sell the power to the region and maybe throughout the continent.’‘Colonisation!’ Siya said.

Later that night, Siya Mfundo and Gina Setzin sat in Mfundo’s hotel room and combed through the agreement, looking at contentious provisions, trying to figure out options, and marking their own redlines. It was after midnight when they finished. Gina gave Siya a warm hug. He watched her from behind as she walked towards the door. She turned her head. ‘Thank you for all your support. You are great boss, Siya.’ He smiled at her and she was gone. When he slipped into a peaceful sleep, he had no idea that the next morning would change everything.

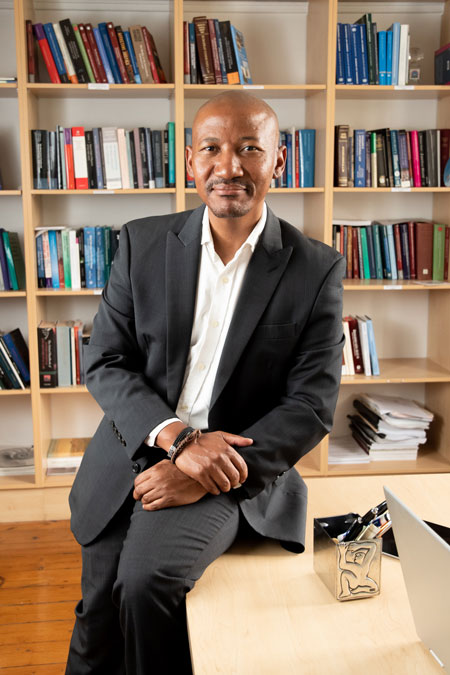

About Dire Tladi

Professor of international law and holder of the SARChI Chair in International Constitutional Law at the University of Pretoria with over 100 academic publications (articles, books and chapters in books). He holds BLC LLB degrees from the University of Pretoria, an LLM from the University of Connecticut and a PhD from Erasmus University Rotterdam.

He is also a member of the UN International Law Commission, and its Special Rapporteur on Peremptory Norms. He is also a member of the Institut de Droit International, and a two-time Fulbright grant holder. He was previously a lawyer for the South African Foreign Ministry, a position that saw him serve a four-year stint as Legal Counsel for the South African Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York. After leaving government service, he was retained by the Foreign Minister to serve as her Special Adviser, a position he held from 2014-2018.

Tladi, has written one other work of fiction, Blood in the Sand of Justice, which has received rave-reviews.

.Extract from Sins of the Father by Dire Tladi. Published by Porcupine Press. Available in all leading bookstores. Recommended Retail Price: R320.00