Maye! Maye! mines the mining history of Johannesburg in general and KwaMai Mai and its surrounds in particular

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

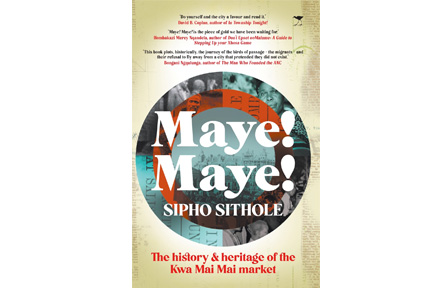

Maye! Maye! a debut book by anthropologist Sipho Sithole mines the history of Johannesburg in general and the famous African traditional market KwaMai Mai in particular, situated east of Johannesburg.

But before I go there, allow me to indulge you to my recent reading habits. In recent months I developed an interest in reading books that we often put at the back shelf of our book shelves, books that in most cases are out of print.

These book sometimes have pleasurable literature that needs to be revisited and read, again and again. I found myself plucking two such books out of the bookshelf: Afrika My Music, a second memoir of the late academic and shorts story writer E’skia Mphahlele that he penned after the most famous memoir of his Down Second Avenue, and When the Lion Feeds by the late Wilbur Smith. What is relevant though in this case with regards to Sithole’s book titled Maye! Maye!, a biography of Kwa Mai Mai Market and its surrounds, such as Albert Street, is When the Lion Feeds.

When The Lion Feeds, just unlike Sithole’s is a fictional version of the gold mining activities, which Johannesburg’s development owes its existence to in the late 1880s when gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand, attracting all sorts of characters in search of fortunes. As one can imagine these characters who came from all corners of the world, but mainly the English world, literally dug up Johannesburg, mainly farmland originally owned by the Afrikaaner farmers, looking for the precious metal that would transform their lives into instant millionaires. Some made it, while others’ wish to become wealthy became wild dreams. Even a nightmares.

But a few struck it rich and it is these rich ones that form the main characters in Smith’s When a Lion Feeds. Somewhere in Johannesburg during that time, there was a hotel and a drinking hole that was frequented by these instant millionaires, the Randlords, who congregated after work to celebrate their success with their mining activities by quenching their thirst at this hotel/restaurant place owned by a strong white woman entrepreneur.

We could actually say this entrepreneur is what we could call in today’s context a legal shebeen queen running a legal establishment frequented by the high fliers of today. Dear reader here I am not talking about the notoriously elusive and infamous Saxonwold Shebeen. This one actually existed in Smith’s book. They drank there these Randlords, ate there, boasted there and connived against each other there. These were indeed greedy and unsavoury characters in the main and in some cases even thugs hunting for fortune. That was there and it was a world created in Smith’s imagination as manifested by When The Lion Feeds.

In Sithole’s Maye! Maye!, a an establishment with striking similar habits to that created by Smith in his m=imagination actually existed in reality, also in the late 1880s in Johannesburg, where real Randlords drank, ate there, maybe even boasted there and connived against each other there. Just like in Smith’s novel. This one was located at Albert Street, a street that the author points out is inextricably linked to Kwa Mai Mai Market as it exists today, just as it endured those several centuries to become a market owned and controlled by black Africans, selling anything from cobra teeth to fresh meat. Those afflicted by misfortune or disease also flock there for consultation with the sangomas and inyangas that have stalls there, .

writes Sithole.

Sithole says in the Albert Street joint owned by a strong English lady, again what we could call in today’s context a legal shebeen queen operator, the Randlords, the real wealthy enjoyed drink, food and more in this establishment after a hard day at work and in celebration of their success with the mines. But as they enjoyed all these trappings of success, outside that establishment, there was a lot of vagrancy, and the vagrants sleeping rough, hustling and walking about the park, could not have been black, as blacks by law were not allowed to be in town and would be arrested If they dared walk around Johannesburg in certain hours without a permit. But oblivious to the situation of squalor outside this establishment, the rich and greed enjoyed inside their establishment as they shared inflated stories of their success with their mining claims.

Sithole in Maye! Maye! goes further and points out that ironically Albert Street of today is no different from that of yesteryear, as vagrancy in the same park and surrounding areas is prevalent. Actually Albert Street’s dominant culture is a spill over from that of nearby KwaMai Mai Market.

There is a lot of entrepreneurship taking place along the street, also mainly by rural folk who came to look for fortune in Johannesburg by way of a job, but unfortunately discovered that Johannesburg is generally tough in many respects, mainly when it comes to landing a job. Especially a well-paying job as an unskilled labourer. Sithole points out that most of the hustling people on Albert Street – street car washers, street mechanics, street hair salon owners and taxi drivers from a nearby taxi rank, hail from such places as Msinga in KwaZulu-Natal among others.

They started these businesses to make money and send back home to take care of their families in the absence of a job in Johannesburg. However there is more happening on Albert Street than meet the eye. For example, there is a trade of a different kind going on there, obviously under the rudder, the author points out. On any given day, there is yet visible but obscure trade that is going on there in broad day light – prostitution where deals are sealed but it is not clear where and when the deal is consummated. But the ladies in the street are clearly busy sealing deals with men out looking for fun in broad day light.

They too need to survive in Johannesburg when a job is nowhere to be found, Sithole writes. The culture dominant along Albert Street of today is a spill over from that of KwaMai Mai Market where entrepreneurs selling cultural products emerged and made a relative success of it, with most traders earning more that the country’s minimum wage.

They built this market out of the need to survive in Johannesburg, far away from their rural homes and the stall owners are mostly an intergenerational family, passing the business from the old to the young over the years. Some inherited the businesses from their grandfathers, while some from their fathers. The market has endured difficulties over the years.

Neglected by the apartheid government and by the post-apartheid government, the market has however become over the years a hub for creativity and entrepreneurship by a marginalised community. This community on the margin of mainstream Johannesburg society, used their culture, turning it into a commercial commodity sought by a wide range of people, both the rural folk, the urbanites and curious tourists who flock there every week to sample what KwaMai Mai Market offers to the public. Both products and services such as consulting a sangoma are offered there to those who need them.

In Maye! Maye!, a book written from an academic perspective (Sithole has a doctorate in (anthropology) but in an accessible language palatable to the reading interest of the general public beyond the confines of academic halls, the book unsurprisingly has been on the Exclusive Books Top 10 selling list since it was released two months ago.

I especially like the fact that the author has perfectly located the existence of KwaMai Mai within the context of other existing modern markets at gentrified places such as the nearby Maboneng, Braamfontein and Newtown.

Unlike KwaMai Mai these are places that after the promise that comes with a make-over, they seem to struggle to maintain their shine and soon revert to their former self. For example, Kwa Mai Mai’s neighbour Maboneng, after its make-over in 2009, attracting art galleries, including David Krut Projects, comprising a book shop and print making workshop, Goodman Gallery, Museum Of African Design and world renowned South African artist William Kentridge’s studios, today has morphed into something else. Goodman Gallery is gone. The David Krut Bookstore is gone.

The Museum of African Design is gone. In their places you will find drinking noise holes where the trendy music of today Amapiano will be booming and the young grinding the floor as an emotional response to the South African originated dance music that has taken the world by storm. But in their vicinity, Kwa Mai Mai has not changed. It is still selling cultural products and the stalls are manned by manly Zulu traditionalists hailing from the rural hinterland in KwaZulu-Natal and it is pumping, attracting crowds. Especially with its Shisanyama attracting the young and happening, including the fashionably dressed who may or may not be slay queens who flock there to enjoy especially the braai and phutu that is offered in abundance there.

During my stay in Maboneng, from 2016 to 2021, I must admit I and friends frequented the market on Sundays to enjoy the meat, after which we would disappear into the bars of Maboneng to wash down the food. In the case of KwaMai Mai it is as if time has been not moving. Frozen. What it was when it was started, it still is today. It is as if 1994 did not happen. BEE deal makers and their expensive slay queens did not happen.

The market is still going on as usual, owned and run by African traders, selling the same items their forebears have been selling for centuries. Their hustling and struggling continues. The only thing that seems to have changed is that they are free to move in town, without fear of being arrested, like it used to be the days gone by. And also instead of horse drawn wagons in Johannesburg’s streets, there are cars. And also the place where their forebears used to look after the white man’s horse, is now a home to them and a market from where they trade, for Kwa Mai Mai was a horse stable where some of the current traders’ forebears worked, tendering to the needs of the horses.

Jobe may indeed with his debut book, found his own gold mine, and if not financially so, (as best seller books by local standards are very low), in Johannesburg mining knowledge that will especially be useful to those studying the mining history of Johannesburg in general and the genesis of KwaMai Mai Market in particularly in future. It is a well-researched book that deserves a space on every reader’s bookshelf.

.Maye! Maye!, published by Jacana Media, retails at R360 and is available at bookstores.