“Pissed off’ by the TRC shortcomings debut novelist Lindani Mbunyunza-Memani writes award winning book – Buried In The Chest

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

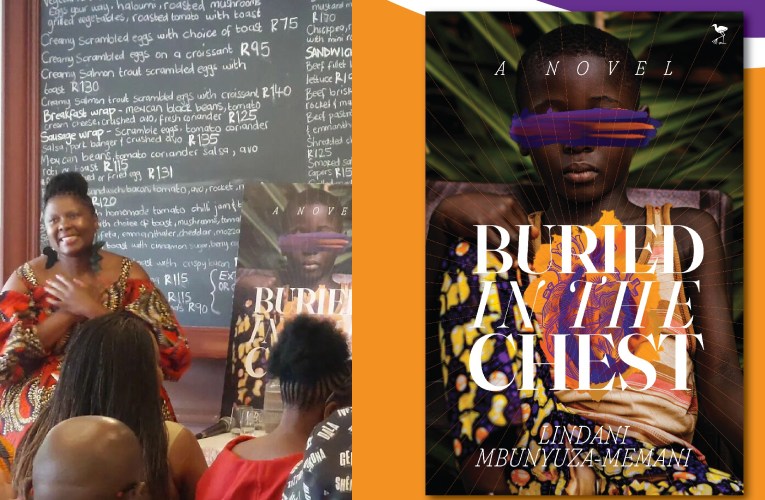

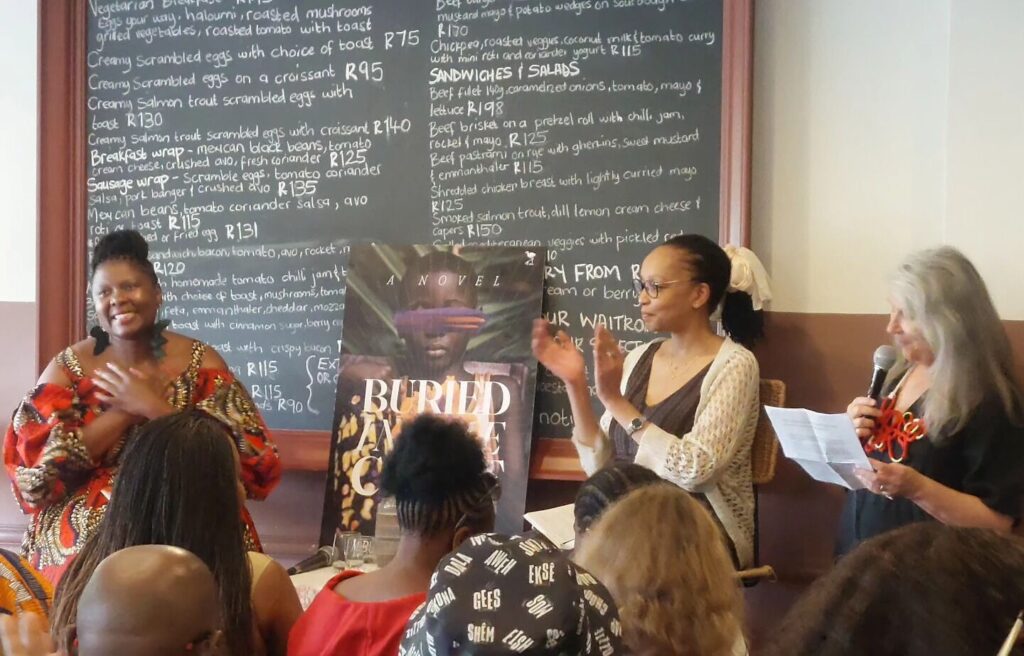

When writer Lindani Mbunyunza-Memani made a presentation of her debut book, Buried In The Chest at its launch at Love Books bookstore in Melville last week Thursday, January 16, 2025, she commenced the proceedings by reading an extract from the book at the very end of the novel. That is before she got engaged in an illuminating discussion with facilitator Karobo Kgoleng, a discussion that gave the audience a deep insight into Lindani’s thinking and her process of writing this debut novel.

The discussion was great as it in a way left the audience yearning to read the book. This is because the writer is quite articulate, unafraid to make strong opinions on a number of contentious issues in society. Be it on toxic masculinity, society’s double standards and sex.

The extract that she read, however, left the audience wanting to hear some more of the book, a clever way of introducing a book to an audience. If anything, Lindani is smart, very smart actually, and it is easy to fall in love with her book by merely listening to her.

For example, through this way, before we actually read the book, we got to know what motivated her to write this award-winning book, the winner of the Dianne Fiction Award (2024) organised by books publisher Jacana Media. It is the truth and reconciliation Commission -rather its unfinished business that frames this novel. The novel is fascinated with the idea that the truth and reconciliation Commission which was constituted after the country attained democracy and was meant to reconcile former enemies through the process of telling all and not be prosecuted for the crimes that one would have committed during apartheid for a political cause., was flawed. That, is as far as making right those whose relatives were victims of apartheid atrocities. The writer holds a strong opinion on the issues. In fact, she is “pissed off”.

This is a word we heard more than four times from the mouth of Lindani, whose daily job is that of Professor at an American university.

“I teach race theory and the issue of race theory is a highly politicised issue within the US academy. Therefore, the TRC issues pissed me off because the process did not result in enough accountability for the actions of those that perpetrated hate and violence. The four people I spoke to who were involved in the TRC process in fact admit as much, and that is that if the whole truth was told through this process the former enemies would not be reconciled. That pisses me off because what it does then is to short-change the victims of violence and their relatives,” she explained.

The extract she read is one that is hard to take in, no matter how much one tries. It is where the man who is identified only as Pa due to his old age on living a farm somewhere in rural South Africa where the events that changed the rest of the country’s political trajectory in 1994, did not seem to have reached. This white man and of course his kind, who did not see anything wrong in proudly hoisting the old South African flag in their homesteads in 1995, even when the rest of the country was celebrating and embracing the ‘new’ South Africa that came with the dawn of democracy.

Is fingered in the novellas being responsible for race motivated murders on his farm. His crimes and those of his associates, included the disappearance of Unathi’s mother Mavis. She hailed from an Eastern Cape rural area called Moya. The confrontation between the pissed off Unathi and the now wheelchair bound, almost dying old racist man, follows the discovery of Unathi’s mother’s grave by Unathi and her ever supportive boyfriend, Gerald. This discovery was not without its own problems though. To start with, the journey to the secluded farm area meant that Gerald and Unathi had to drive through a hostile terrain, the Vrede town where blacks, except those who worked as slaves on the white people’s farms, were not allowed to live in or visit.

This means that that journey that Unathi and her boyfriend undertook was paved with danger. The conservative Afrikaaner community that live there are determined to keep the place, not only white, but Afrikaaner and extremely conservative, seemingly unaware and unaffected by the transformation that was taking place and shape in the rest of the country with democracy in full swing and white attitudes towards their black counterparts softening and accommodative.

That confrontation that takes place here hurts. If you did not read the rest of the book first and just went straight to reading this extract, you would think that Unathi is cruel to this elderly, helpless white man, who due to old age could not speak, or through the immobility could not defend himself when he was physically and verbally attacked by Unathi. This is because seething with immense anger and driven to her emotional limits, Unathi raged. She not only uses extremely violent language, but she is physical with him too. She gives him more than a hot clap, if you know what I mean.

At face value, you would therefore sympathise with the helpless and defenseless old man. But the problem is, here we are not dealing with an innocent old man who should be left alone to enjoy in peace whatever is left of his life. This man and his ilk are responsible for the death and disappearance of many people during apartheid. Those they made disappear were either buried in shallow graves, after their bodies were mutilated, such as Mavis, or their bodies hidden where no relative would ever find them.

The portrayal of this old man as evil and a monster whose hands are dripping with the blood of innocent people, is what makes a reader to not sympathise with him in his difficult situation. This technique of painting a vivid picture of an evil old man who should deserve no sympathy from anyone by the writer is quite clever and useful.

And also, if you first read earlier chapters of the book before this section, you would have known how Unathi lost her mother from her rural Moya Village, where life is strange, where a mysterious wind controls the rhythm of life: When to plant crops. When and how to build the rondavels. It is a place where women, like Unathi’s mother Mavis, disappear after giving birth if they are unmarried. The same fate however does not befall the men who make them pregnant.

To fall pregnant in this Eastern Cape village marks you out as a woman of amanyala. A woman without virtue. This drives many of the rural women folk, like Mavis to go far away from the village of Moya, looking for peace and an opportunity to make a living, and hopefully to look after the children they leave behind, such as Unathi. Unathi was left in the care of Mavis’s mother MaKhulu, who does not help matters a lot when she cannot answer recurring questions from the growing child yearning to know who her mother is and where she is.

Poor, and struggling, finishing school is hard for Unathi. But finish she does. But when the only relative and caretaker she has ever known passed on, MaKhulu, one can imagine how that affected the then teenage girl about to matriculate. So here the writer uses the difficult conditions in which Unathi grew up, without a mother who was victimized, violated and eventually killed by racists to justify Unathi’s anger and treatment of the man responsible for the pain and the indignity suffered by her mother and several other black people who mate the same fate in the hands of the racists oof Vrede.

But luckily for Unathi, help is at hand when Mr. Bruso, a caring elderly man who was close to the late granny prevailed and took it upon himself to mentor and look after this teenage daughter who ends up at a teacher training College where her life and that of Gerald collide.

Again, as they first met during the funeral of MaKhulu as Gerald’s Afrikaaner father ran a funeral parlor that buried those who died in Moya. Gerald a teacher himself at a local college, is the one who enabled Unathi’s admission at a teacher training college in East London. But this time, love is in the air. In fact, Gerald’s presence in Unathi’s life becomes more than a romantic connection. He also coming from a complicated but different heritage, father white and Afrikaaner, mother Indian and disappeared, sealed both of their fate.

But now that they are here in Vrede, where the love-struck Gerald at the risk of falling to pass a bizarre test to determine whether he is white and Afrikaaner enough, is determined to assist not only his girlfriend find closure over the disappearance of his mother, but others in similar circumstances, whose issues were not solved by the shortcomings of the TRC process.

One therefore after reading this book understands why Lindani’s words at the launch were punctuated with the then famous “what makes me pissed off phrase peppering her dialogue with Kgoleng and the audience.”

By saying this and framing Buried In The Chest within the context of the failure of the TRC process to find closure for victims and relatives of the victims of apartheid violence, Lindani is speaking for many others whose voices are muffled. Struggling to be heard, prematurely suppressed by a less than perfect process that attempted to right the wrongs of the apartheid past, but failed.

What I especially like in this novel is its setting, which unlike several books that have been written in recent years, think of Niq Mhlongo’s The City Is Mine, which is set in suburban Linden in Johannesburg as well as Johannesburg CBD and Durban CBD, and Zukiswa Wanner’s latest novel Love, Marry Killer, which is set in both suburban Harare and Johannesburg CBD.

Therefore, while there is nothing wrong with making the setting of fiction in big cities, and certainly nothing wrong with the suburban settings of the above two books, in recent years there has been very few literary works that are set up in the rural areas. After all, people live there, fall in love and out of love, and certainly die and get buried, just like in the big cities.

And so as far as this novel’s setting is concerning, this is a breath of fresh air, reminding one of the legendary short stories of one Herman Charles Bosman, who through his short stories that vividly capture the lives of rural Afrikanner folk changed the popular perception of rural areas as existing boring places with no life to talk about, let alone write about. In buried in The chest, Lindani is following in that tradition of making rural areas alive with possibilities, when it comes to making such often forget places in contemporary South African literature once again viable settings for novels.

Also in this book, I like some of the literary techniques Lindani uses here to tell this complex story of unresolved issues of the past emanating from the days of apartheid.

For example, her approach about these issues are nuanced, told through the lives of her characters, told in an oblique way, a technique that literary scholarship advises should be employed cautiously. This is because a traumatic event written in an oblique way, powerful as it is as a literary technique, has the potential to trigger those of the readers who have for example experienced the same issues in their lives.

It is clear here that Lindani here has employed oblique writing in a clever way, as it induces a sense of collective outrage from readers about the unresolved issues emanating from the TRC process, a sense that justice has not been fully served but that flawed process that encouraged the victims to forgive and move on irrespective their gaping wounds inflicted in the past.

Buried In The Chest is therefore a powerful novel that deals in an effective way with a painful past whose memory will linger in the subconscious minds of many a South African, and this is as the process that was meant to mitigate that pain of collective memory, the TRC process, is in hindsight found to be flawed.