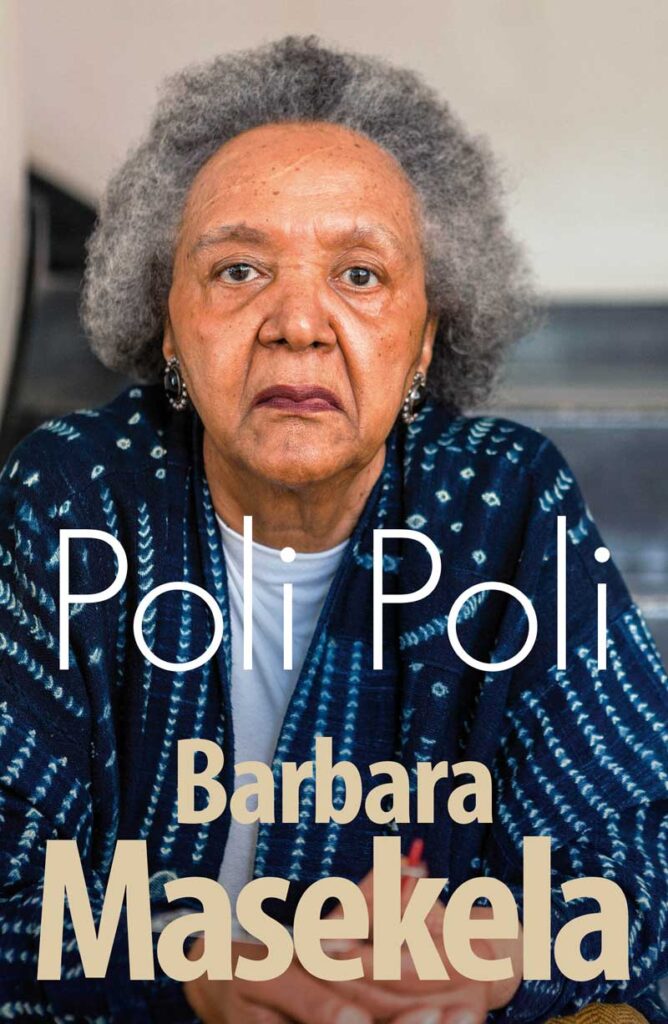

Poli Poli a story deeper than profiling Barbara Masekela’s life, but also reflects on legacy of apartheid

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

Barbara Masekela the veteran freedom fighter turned diplomat, has had a colourful life in some of the world’s leading capitals both in pre-1994, when she was in exile mainly in the US, and post 1994, when she became a business leader and a diplomat.

It is however the tales she tells in her new autobiography Poli Poli published by Jonathan Ball Publishers about her childhood, growing up in Witbank, that especially appeals the most to me. This is because besides knowing the lives and times of the prominent Masekela family, one gets to understand Barbara’s political genesis. It is mainly due to the childhood horror stories told by her grandmother about how the apartheid government disposed many black people off their land around Witbank, only to be replaced by very poor whites, who only managed to make the land productive through the exploitation of the former land owners who were forced to work for them for too little or as slaves to the master.

These stories filled with sadness of how her mother’s people, the Ndebele people of that area and their chief were treated, told to her when she was very young politicised the young Barbara and made her aware of the situation in the country as she grew up, especially with regards to white people in general and the unequal relationship with black people.

While her parents were in Johannesburg, her grandmother Ouma, as Barbara calls her, was the matriarch that made sure that there was food on the table to feed the young Barbara and, even sending Barbara’s mother to tertiary school when she was in marriage already. She did this by running a shebeen in the township of KwaGuqa, where they lived.

Barbara’s bother, the late world renowned trumpeter, Hugh Masekela was living in Johannesburg with their parents, and would only occasionally go back to KwaGuqa during school holidays. He left for Johannesburg to join his parents when he turned 7.

Barbara in this book told with amazing honesty also tells of how her older brother, would get into trouble with the strict Ouma because of his mischief once there, including jumping over the fence of white farms to pick up fruits for example. Black people were not supposed to enter these farms except for work purposes, but the young Hugh did, and each time he did so, Ouma would give him a hiding. He received several such hidings during the school holidays whenever he was in Witbank.

But what is also interesting in Barbara’s book is that through the tales of the often wretched lives of black people in KwaGuqa, such as her grandmother, Ouma, a widow once married to a philandering white South African man of Scottish origin called Walter Bower, who died in 1938. When he died he was in the home of his mistress in Doorfontein. His wife Ouma had to come and collect vhis body to burry back home as they were legally married. The point is through these tales of her grandmother, the cruel hand of apartheid and how it destroyed black people’s lives comes through sharply.

For example, the people who lived in KwaGuqa of Barbara’s time were mainly those whose forebears had lost their land to often poor, white rural folk that were given the land by the apartheid government, and in the process affecting the lives and livelihoods of black farmers and families, the rightful owners of the land.

As their land was taken away forcibly, displaced black families had to either rent a piece of land from the poor white farmer who had been given their land or leave and go to be resettled in KwaGuqa or elsewhere, to any area reserved for black people. KwaGuqa was one such area in Witbank where black people could live. But the hand of apartheid did not leave them alone as they were still policed in a racist way even there, including carrying passes in this mainly mining town.

To make it worse for those displaced, those who did not, or could not leave, but did not have money to pay rent to the white farmer to remain there, they needed to sell their labour to the white farmer for a period of time in order to remain on their own farms as tenants.

And also through Poli Poli, one also gets to understand excruciating white poverty of the time. The whites that were handed over these farms were poor, and they were perhaps in the same position in which a majority of black people find themselves today. But because of some sort of affirmative action that the government of the time implemented in favour of the poor whites of the time, to advance them economically, often at the disadvantage and exclusion of blacks, they managed to take themselves out of that uncomfortable position of poverty to a comfortable position in life.

This fact is quite important and crucial to understand the context of post 1994 South Africa and the failed attempt that the post apartheid South Africa government tried in implementing affirmative action policies aimed at advancing black people in general. The policy itself was not a bad idea, as it was once used successfully in this country by the apartheid government. The fact that this policy failed to take black people from poverty to a comfortable position in life, is not because the policy itself does not work. The fact is it works, but unfortunately the post apartheid government failed to implement the policy successfully, and this is the bitter pill all of us have to swallow, especially policy makers in the post apartheid South Africa. They have mainly failed black people with regards to successfully implementing Affirmative Action policies to pull black people out of poverty gradually.

“Much later, I begin to understand. Apartheid is designed to permanently erase the memory of that time when whites were dirty, poor, homeless workless underdogs. It is desingned to erase that a black child will never again see a poor white person. Indeed the new laws under the regime of apartheid are legislated one by one so that no white person should ever be without food, a house, a job, medical care or an education. Even then, I shielded myself from imagining my grandmother as a child. Instead I laugh with my peers at their songs, their food, their clothes, their rules, their beliefs, rushing only to adopt the latest of everything.

“In her restraint Ouma never tells me about the wars of attrition in which the Ndebele Ndzundza Chiefdom, from which her family came, slowly lost their land, autonomy, ways of life and material freedom. She says nothing about the Voortrekkers who first paid tribute to the early King Mabhogo to be granted the right to use communal land for grazing and cultivating, and who with the active mediation of early missionaries ended up making demands,” writes Barbara as she reminisces about her childhood and how she got to understand the place of her grandmother and her folks in apartheid South Africa.

In the book Barbara speaks a lot about her more famous brother, the late world renowned trumpeter Hugh Masekela who she addresses mostly as Minkie, the childhood name she called him by as they grew up.

Barbara makes it no secret that they grew up close even as Hugh left Witbank at the age of seven to live with his parents who were living in City Deep, Johannesburg, where his father first worked as a mines police before he was promoted to the position of mine clerk. Thomas Masekela was however ambitious and studious as he continued to upgrade his education, eventually becoming a health inspector.

He was also very artistic as he pursued further skills in art, and became quite good at it, especially sculpture. He was well known in art circles, including rubbing shoulders with the likes of Gerard Sekoto and Dumile Feni, before they left for overseas, with Sekoto basing himself in Paris where he eventually died.

When Barbara went to exile, based in the US, London and Lusaka, she rubbed shoulders with her father’s contemporaries, including Feni and Sekoto, who she met in Paris in 1964, and he was surprised when she told him that she was Thomas Masekela’s daughter, and so did Feni, Barbara reveals.

However what is also clear in the biography is that although Thomas Masekela was a prolific, even a bit obsessed with making art, he seemed to struggle to commercialise his artistic activities, when his peers, such as Alexis Preller and other seemed to have been more successful commercially. And this Barbabra speculates, could be because he was black and therefore opportunities for success in art were difficult for people like him, whereas his white contemporaries did not have such a disadvantage in the art market during apartheid, she argues.

However back in South Africa after 27 years in exile in the early 90s, Barbara made an attempt to trace her father’s artistic endeavour, and indeed found out that his footprint on South Africa art was indeed there. In fact his works were even exhibited at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, and some of the works are understood to be in the collection of Fort Hare University.

The author however seems to have been disappointed by the lack of commercial opportunities for her father. He was simply not afforded to practise commercially and make a success of his art career, just like the Alexis Prellers of the time.

Barbara has therefore not bothered to go and see her father’s collectionart works at both institutions. The reason, it sems, Barbara is still angry about the way her father’s artistic practice was treated by the art establishment when he was still alive.

Poli Poli, is therefore a good book to read, especially if one wants to know about the background of one of the prominent families in the liberation struggle, the Maselekas, but also to understand how the system of apartheid affected particularly black people going back to the 40s, when Barbara was a toddler (She was born in 1941).

Poli Poli therefore is not just about the life of this former diplomat to France and the US and her family, it is also about the history of this country and how the issue of apartheid loomed large in the Masekelas’ lives, just as it in the lives of many black families, including land dispossession and servitude in the hands of Afrikaaner farmers that took over black land assisted by the government and made the rightful owners to serve them or leave.

It is story of pain and the triumph of the human spirit, as Barbara lived to tell this painful story of her upbringing under apartheid in a free country, which has afforded her opportunities to serve in corporate South Africa as well as in the public service as a diplomat to leading countries in the world.

.Poli Poli by Barbara Masekela, is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers and is available at bookstores retailing at R300.