Strikingly hard eye keeps your head nodding and bobbing

By Jojokhala Mei

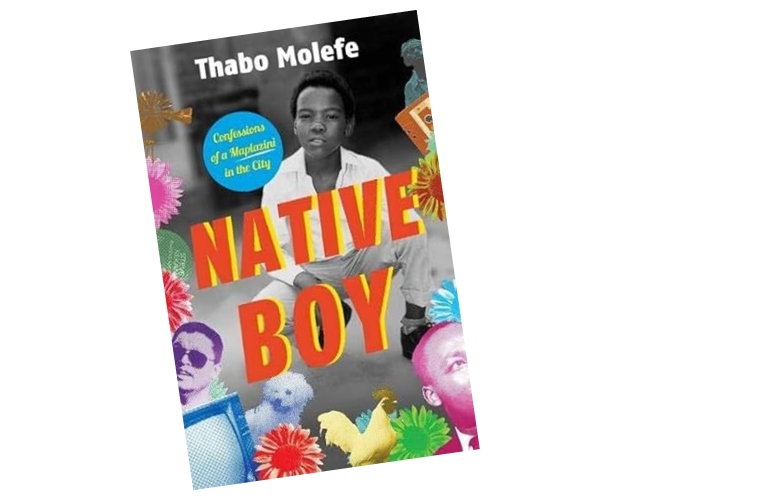

Thabo A Molefe’s debut 2021 novel NATIVE BOY – Confessions of a Maplazini in the City is bouncing 210 pages of decent print size; with a ‘Young Adult Literature’ busy fresco cover that belies the heavy weight punches it pulls.

Sommer like heavyweight boxing champion Mohammed Ali’s The Greatest: My Storystormy autobiography, written with journalist Richard Durham. Not to mention that Molefe’s flair for the flavor of his childhood rural and cityhaunts and language lives up to Prof EskiaMphahlele’s own path-finding autobiography, Down Second Avenue. Like Thabo’s young adult nick name ‘Timber’ given just for the sound of it. Nothing else..

Because I don’t know the author from a bar of soap, I fear this could be another motivational book, with no singular compelling life story to tell. But generous scattering of fond black-and-white family photos pulls me in. When in doubt I usually shoot straight to the closing pages to get a measure of the eloquent gravitas of the story. Afterall, some of the best movies I’ve seen start with turn or end to the story, before taking you to the beginning panting to find out how it all started. But no personal story is wrapped up at this closing. It’s all theoretical pontification of South Africa’s socio-political controversial landscape by a stranger..

Neither does the book\s introduction spin anything beyond a stranger’s criticism of workplace discrimination in South Africa well after democracy. But tell it to the birds mate – I’m an African too, you know. The discriminators know it all too.

So I skip the introduction to give Thabo Molefethe last chance to show up. Now the jolly good ride of my life begins. I wish the publishers note this.

Thabo is the last born 6 year old of a farm tenant family in the far eastern Gauteng province corner town of Heidelberg – of racist Eugene Terreblanche infamy.

From start is an improvisational interplay between Thabo’s adult voice, and the 6 year old Thabo’s strikingly hard observant eye – like all children of that age group have.Enjoy a privileged ringside seat watching Molefe’semotional intelligence grows by leaps and bounds in ‘imitation’ofboth parents who both cunningly wriggle their way out of working for the farmer as is customary. Let alone his father daring to buy his own smart caris uncustomary. His mother pulls off a coup for those savage racist years when she gets a liberal domestic household employer to lend the family money to buy a housing stand in the township of Ratanda , also in the Heidelbreg district. And they literally build their own comfortably big house, amidst the side-splitting friends’ camaraderie of first dates, and all.

Both his parents’ ingenuity proves to be Thabo’s living heritage, but it is hard to figure out exactly why and how his elder brother, Nikki, seems to have fallen off the tracks growing into young adulthood, and eventually the men he became. The adult Thabo casually slips in some growing up lessons like owning a football team around his early teens. He notes: “In my four years as a team owner I found that the ability to find the root of the challenge presented by our opponents was not only desirable, but indispensable. This for me is equivalent to what might be termed by management theorists as the core competence of a team owner-cum-coach. It was a common occurance for a team to go too easily into a challenge, underestimating their opponents, and overestimating their chance of victory.’

One can only hope that Thabo has changed the names of two or three people who come under scathing criticism, chief of whom is a one-time friend, Vincent, who tipped him on a banking ‘apprenticeship’, but turned out to be his worst enemy in the end. For the sake of fairness the Adult Thabo could have expanded on what Vincent pointed out as Thabo’s own personality faults. After Vincent falls off Thabo\s radar for many years he crops as: ‘For their part Africans like Mlungisi both bemoaned and felt ashamed by the sudden loss of their treasured White neighbours . A few years later in 2005 I heard of the depths of shame felt by Africans who wittingly or unwittingly become residents of formerly ‘whites only’ suburbs that had become ‘majority black’, or worse ‘blacks only.’ This happened when Vincent bought a house in the middle class neighborhood on Gauteng’s East Rand.’ I felt like screaming to keep Vincent off his radar.

ThenThabo has the courage to criticize his own father’s interactions with his brothers, who are Thabo’s uncles. Yet Thabo never admits to any faults of his own. This is the only fault I regrettably find, and remain open to correction on a blazing brave all-time story.

I had to throw in that criticism only for balance, because this is a jolly good Black Friday and festive gift to yourself or another, worthy of even aunt Oprah Winfrey’s gift stockings. For the good of summer I will never know why Thabo ‘Timber’ Molefe seems to still take offence to the ‘maplazini’ label by residents of inner Ekurhuleni Metropole of Gauteng province, when those detractors suffer same slur from townships of the main Johannesburg Metropole!

JONATHAN BALL PUBLISHERS, 2021. Also available as an ebook. See info@thabomolefe.com

jojokhlalam@gmail.com