The book amplifies the voice and presences of black photographers within the contemporary image making practice in Africa

Those featured in this book are photographers Tshepiso Mazibuko, Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni (Thokoza), and Haneem Christian (Cape Town), is also accompanied by text of various length and textures written by award winning photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa and researcher Dr. Candice Jansen.

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

“Making images is a practice that allows me to pause, take up my camera and freeze time, delve into small details we might otherwise miss had we not been given a chance to photograph them,” writes photographer Litha Kanda, a text that accompanies his photographs in a new book titled The House of Story. His series of photographs in this book focus on the theme of birth and the relationship between new parents and the child that is growing in the womb and waiting to be born.

The book which also has photographs of young leading photographers from the East Rand and Cape Town, Tshepiso Mazibuko, Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni (Thokoza) and Haneem Christian (Cape Town), is also accompanied by text of various length and textures written by award winning photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa and researcher Dr. Candice Jansen, the former gallery manager of Market Photo Workshop.

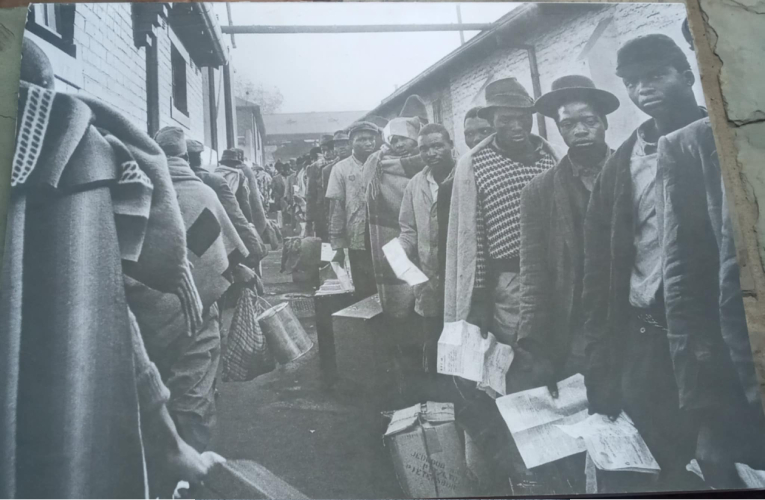

These photographers in the book are part of the images the three photographers created in a project that exposed the photographers to a selection of the photographic archives of Magnum. Each of the participating photographers had their own take on the archives as a way of response, and each one of them looked at the archives and interpreted them in their own way. It is however interesting to observe that all the participating photographers approached the project by looking closer home, archives of their own communities, and in the case of Mabula, looking at her own family history, and Mazibuko her own community of Thokoza.

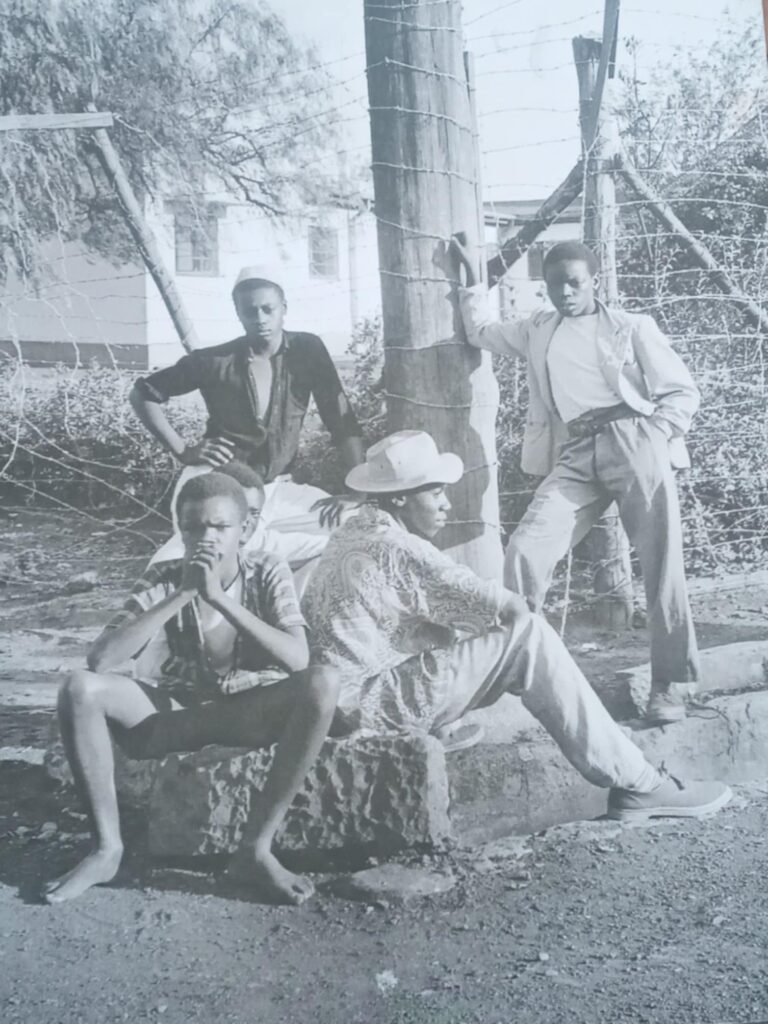

“Initially when I began the body of work, my intentions were to create a visual archive of the township landscape. This was heavily influenced by my need to be part of the generation of photographers who are building an extensive archive of black bodies. Driven by making an accurate representation of a people as a driving force, to a certain extent allow stories told by us for us,” writes Mazibuko, and further asks the question: “Does it matter who creates an archive, an insider or an outsider?

She however alludes to the fact that documenting her own environment in which she grew up, a township that she has both an alienating and an intimate relationship with was not easy. Mazibuko’s relationship with the township in which she was bo0rn and grew up is clearly complicated.

“I found it hard photographing the work, photographing how it felt to be there, my childhood recollections, unclear memories of my late gran. Death always comes into play. Was I ready to have a conversation with this landscape that has made me, but that has at the same time broken me? Family broken, relationships broken, lovers broken, friendships broken, broken dreams. The unease feeling whenever I am at certain spaces, certain figures, some drifting away, some in deep contemplation, others not visible, just existing, drawn to the less obvious, selective viewing,” Mazibuko writes in prose form about her experience of encountering the archive and responding to it in an almost personal way. Her series it titled AwukhoUmdlaloOngenababukeli: There is always someone looking.

“Memory is the narrator and through it is often an unreliable memory is the author of the prose that becomes us, who we are who we were and who we will become,” writes Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni in a poetic text that also carries literary merit in a form of short stories. Her series is titled Umbdeshowamathambo. She describes her undertaking as “a personal introspective look at my family’s own archive as well as its implications on me and the person I am becoming.”

Christian’s body of work in this book was inspired by the late Queer Cape Flats activist and archivist called Kewpie and hence the title Kewpie se Kind: Kewpie’s Child. The series of photographs seek to normalize queer presence in contemporary Cape Flats community. The legendary activist, who made their name is Queer communities among the Coloured Community during the apartheid years by rebelling against being rendered invisible by a system that never recognised their existence by sticking their neck out and speak back through archiving Queer existence making it visible is to9day a mythical figure in Queer literature. Kewpie is said to have archived Queer culture in the Cape Flats during and even despite the restrictive nature of the apartheid system of the time, which not only refused to acknowledge the presence of black bodies in general, but queer culture even more so.

“The people photographed here embolden young Queer people from the Cape Flats to envision themselves beyond the boundaries and binaries. Kewpie se Kind offers a different eye to see ourselves and a different eye to see ourselves within our homes. An eye that offers a more abundant truth,” writes Christian. The photographs depict images of Queer bodies in different settings within the Coloured Community in the Cape Flats.

Jansen’s text looks at the issue of a problematic archiving that by mainly European archivists who in some cases, did not bother to write captions of the images they took from Africa, while Sobekwa’s text critics archival repositories such as Magnum for not opening up to new people as members from the Africa. Sobekwa in his text also problematises the practice of othering photographers from the global South by such repositories of history, and instead suggest that they too should be invited and feel at home in such international archival repositories as they too have an interest in them as practicing image makers.

And so The House of Story is an important book, and not only because it gives an opportunity to black photographers to gaze closely at the archives of their own communities, but also to get to hear their dreams and the challenges they face in their art practice.

In other words, this book amplifies the voice and presences of black photographers within the contemporary image making practice in Africa. The House of Story was sponsored by the British Council in South Africa and Rubis Mécénat.