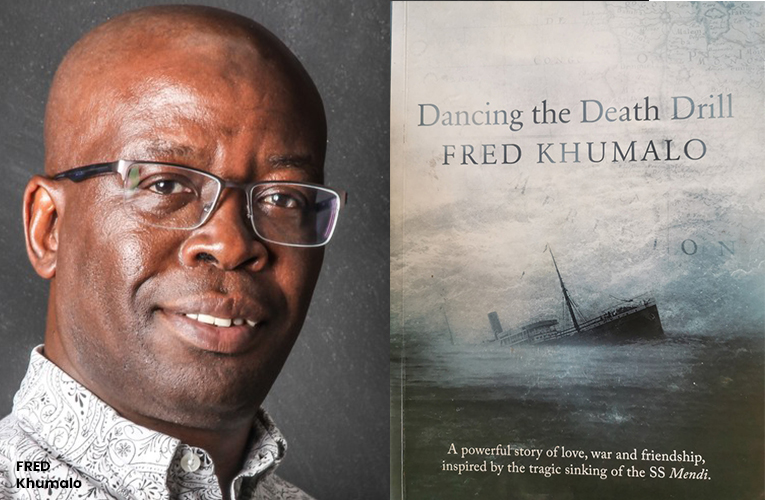

The historic novel Dancing The Death Drill by Fred Khumalo takes to the stage at Joburg Theatre opening on Friday

Dancing The Death Drill a novel by Journalist and novelist Fred Khumalo that has been adapted into a stage musical that opens its season this Friday at Joburg Theatre, is a well-crafted piece of writing about the tragic sinking of First World War ship SS Mendi one February 1917 in which South Africans perished, says writerJojokhala Mei reviewing the book ahead of the musical play’s premier.

By Jojokhala C Mei

…………………………………………………………………………..

UKUTSHONA KUKAMENDI ngu S. E. Krune Mqhayi (1943)

Ewe, le nto kakade yinto yaloo nto.

Thina, nto zaziyo, asothukanga nto;

Sibona kamhlope, sithi bekumelwe,

Sitheth ‘engqondweni, sithi kufanelwe;

Xa bekungenjalo bekungayi kulunga.

Ngoko ke, Sotase! Kwaqal\’ukulunga!

Le nqanaw’, uMendi, namhla yendisile,

Nal” ‘igazi lethu lisikhonzisile!

………………..

SINKING OF THE MENDI

Yes, this thing flows as a normal thing from that.

The thing we know is not scared of that;

We say, things have happened as they should have,

Within our brains we say: it should have been so;

If it hadn’t been so, nothing would have come right.

You see Sotase, things came right when the Mendi sank!

Our blood on that ship turned things around,

It served to make us known through the world!

Legend has it that such exquisite lament by Xhosa-language poet laureate S.E.K. Mqhayi flowed instinctively at the Cape Town docks to news of 646 men (wikipedia) drowning when the First World War ship SS Mendi sank one February 1917, it is a wonder to wait so long for James Ngcobo and Palesa Mazamisa’s drama-cum-musical stage adaptation of Fred Khumalo’s acclaimed 2017 historical novel Dancing The Death Drill to finally open on the Mandela mainstage at the Civic Theatre, Johannesburg on Tuesday the 8th of September 2025.

Our guarded hero with a chip on his shoulder insists to call himself Pitso Motaung, from the Free State province. Yet he is a curiously endearing fellow, to use what novelist Khumalo calls ‘Lovedale English’. Pitso is one of the Black men on the SS Mendi recruited to strictly handle all the war baggage used by the White soldiers because racist South African laws prevented black soldiers from defending themselves from murderous fire of the German enemy; let alone take the initiative to kill them. No wonder the men dubbed the enemy “Mkhize” with begrudging affection.

Indeed, petty racist vitriol characterises relations across the colour bar to the point of: ‘Fuming torrents of spit out of his mouth, the white officer said, “Tell this monkey that the point here is not to simply carry a bag from point A to point B. Tell him we’re testing everybody’s strength, chief or no chief – to see if they qualify to go overseas. We can’t carry sick burdensome bastards across the seas. We’re going to war, not to a blooming picnic. Tell the blockhead what I’ve just told you!”

Pitso, even though he was a recruit himself, was working overtime to translate to his comrades the white man’s words. He had the good fortune to be able to speak Afrikaans, his father’s language, which was spoken widely by the white people in Bloemfontein. But he could also speak his mother’s language, Sesotho, and impeccable English, which he had of course learnt at the centre for coloured children.’

Pitso would not join that famous death drill on the sinking SS Mendi led by the chaplain reverend Gqoba. Instead, the injured Pitso will fall hopelessly in love with a white French nurse (high-five Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell To Arms))

Khumalo, a seasoned journalist, researched and wrote the novel with academic cumbersome precision for his MA in Creative Writing at the University of Witwatersrand; but he doesn’t milk the bleeding racist irony of black porters-cum-soldiers as dry as fellow African and 2021 Nobel Prize for Literature winner, Abdulrazak Gurnah, is wont to do at every turn, for instance in his novel By The Sea. Here a refugee flies into Britain from the island of Zanzibar in Africa with very little besides the treasured perfume:

‘Ud-al-qamari: its fragrance comes back to me at odd times, unexpectedly, like a fragment of a voice or the memory of my beloved’s arm on my neck. … The ud was the resin which only an aloe tree infected by fungus produced. A healthy aloe tree was useless, but the infected one produced this beautiful fragrance. Another little irony by you know Who.

Indeed, you know who.

The novel Dancing The Death Drill may fall short on polishing historical detail and the colonial ironies it picks on, but is set to score the monumental losses of life and love won with the haunting score of gifted musician Msaki, and choreography by Luyanda Sidiya.

The novel introduces Pitso at the end of his life, accused on the living side of a double murder. For the story of his life to ominously slither a death drill of a kind that some people call fate, as sure as philandering Pitso’s slow love dance floor moves.

Indeed, Pitso’s psychological journey is a tour de force, that matches up to the sinking drama of the title, as the seafaring lives of the captured slowly takes centre stage this century in Joanne Joseph’s iconic South African novel Children Of Sugarcane; to stand as tall traditional seafaring literature like Anthony Trew’s The Moonracker Mutiny, or the USA’s iconic novel Moby Dick.

Still, this is a story well told enough to stand up to inga Somdyala’s monumental 3-storey high sculpture of a red ship sail on permanent exhibition at the University of Pretoria’s Javette Art Centre. Somdyala calls it a tribute to our South African seafaring tradition, and it would stand floor-to-ceiling of the Johannesburg Civic Theatre’s cavernous reception.