Len Kumalo’s exhibition affirms contribution of black photojournalists in shaping narrative of South African social and political history

By Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

When I started working for Sowetan in 1998 just as I was completing my journalism course at Pretoria Technikon, I wrote in the area of entertainment. My job was mainly about interviewing celebrities working in television, radio and in the music industry. It is then that I found myself being assigned to stories with several photographers, and most of them were veterans of the photojournalism trade.

It was at a time when newspapers were in a position to hire as many photographers and of course as many reporters as they required. It was during a time when newspapers played the main role of “informing, entertaining and educating” the masses of people. A time when the business of running newspapers was big business, and even lucrative for owners and therefore publishers did not place strict restrictions on editors when it came to how many staff they required and hired. A good number most of the staffers in newspapers were experienced professionals who had polished their craft of over many years and were therefore in a position to mentor many a young reporter or photojournalist.

For example it was normal on a single day for a reporter to be accompanied to three different assignments by three different photographers in one day. All on the newspaper’s payroll. Most of the photographers I found at Sowetan were veterans of the journalism field who of course worked alongside a few young photographers and reporters.

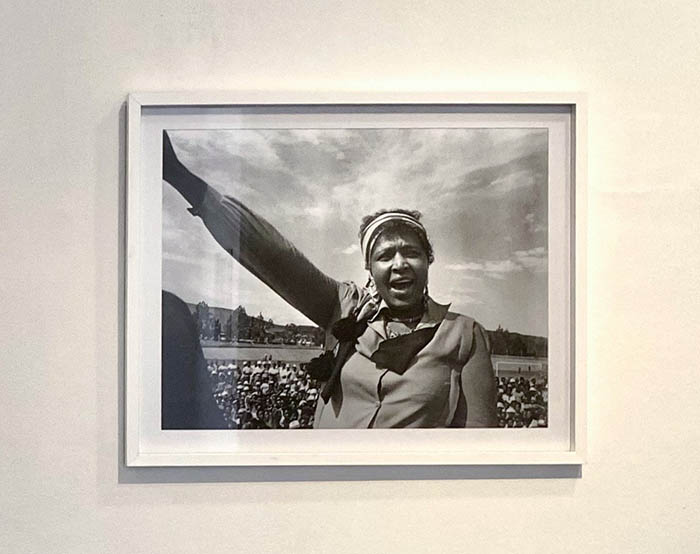

These old photographers not only had played a huge part in shaping what one could call black journalism in South Africa, but the struggle narrative as well. They often told stories that pointed at the destructive impact of apartheid policies in black townships prior to 1994. Stories that demonstrated the wretchedness of black lives in townships as mainly impoverished township people tried to ache a living under conditions of oppression, navigating their lives carefully along the social and economic restrictions imposed by apartheid policies. These are people who tried at best, but not always successful, to avoid being on the wrong side of the law. Because of terrible social conditions they found themselves in, hopelessness and a violent streak developed among the defeated and therefore violence became one of the defining features of a black life in the townships during that time. Adding this to the state sponsored violence, townships actually became places where life was cheap. To die any time of a violence of one sort or another was not something that those who lived in the township did not expect on a daily basis.

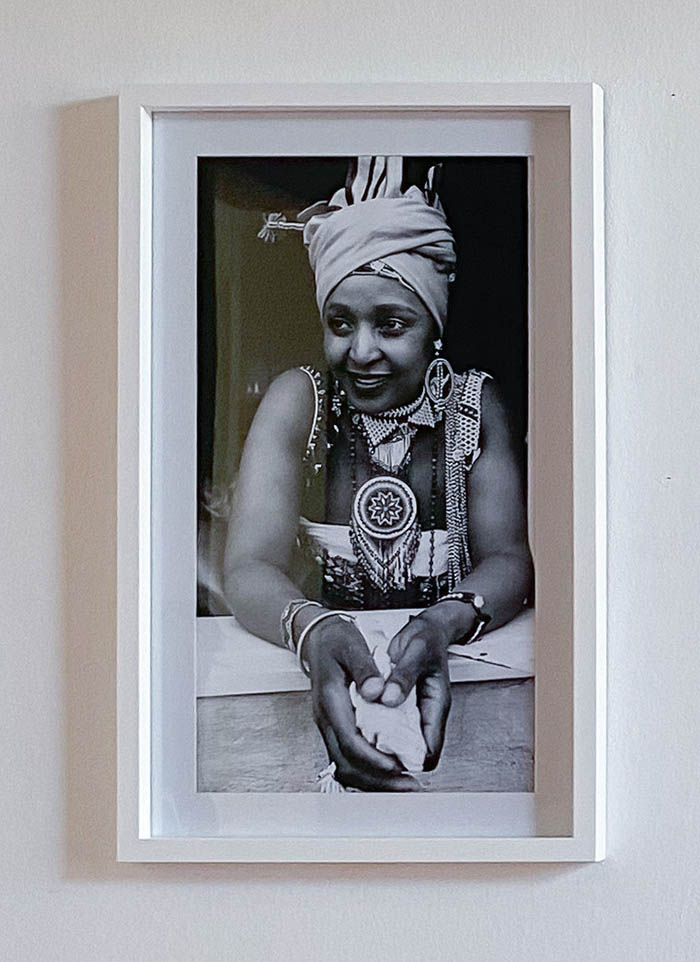

But there was not always violence only. People lived decent lives. They even dreamed good dreams. They fell in love and got married. They brought up children who made something meaningful out of their lives. They celebrated good lives. Watched their favourite Orlando Pirates and Kaizer Chiefs take on each other of the field of play. They went to church to pray to God. They danced to jazz, and Bubble gum music. They started businesses that failed and succeeded.

We know all this because black Journalists and photographers most of whom lived in the townships alongside the people they wrote about, were therefore the ones who documented all this. You only need to go to newspaper archives to mine all this information from 1993 backwards.

I arrived at 61 Commando Road, Industria, in 1998, fresh from journalism school, four years after the country attained democracy. Hope was in the air for many in the country, especially the formerly disadvantaged. They looked forward to a better life than the one they lived during apartheid. This is the context in which my career in mainstream media started.

I found these veterans there who had witnessed and documented atrocities perpetrated by the apartheid state, including the so called black on-black political violence that wreaked havoc in people’s lives in the townships in the early 90s. These were photographers who witnessed and documented these traumatic events. But in post-apartheid South Africa they had to work alongside young reporters fresh from university. Like me. It was therefore often not unheard of for a senior photographer accompanying a young reporter to an interview, to intervene and ask relevant questions whenever such a reporter seemed to miss a point. Just for the sake of the poor reporter of course. But of course to senior reporters, this habit became an annoying and unnecessary intervention. That is if a photographer also interviewed the subject alongside taking pictures. But in the main indeed the wisdom and experience of the senior photographer intervening and asking questions for the benefit of a young reporter, helped to shape the interview. Certainly the story.

One such senior photographer I found at Sowetan, and who was helpful to young reporters on assignment is Len Kumalo. A gentleman really. He is the younger brother to the other legendary photographer, the late Alf Kumalo. Whenever I went to interview celebrities, Bra Len sometimes would jump in and throw his own question to the interviewee. I did not mind him. In fact I found most his questions to be quite helpful. Intelligent even.

But in the newsrooms behind his back, other young reporters often gossiped behind Bra Len’s back that he liked to interfere during their interviews. Some even complained that he was disruptive to the flow of their interview. But to me, I found his intervention If curious, helpful. This is because in most cases, Bra Len knew these interviewees better than I did, and would ask them to talk about things about themselves that I never knew. This applied particularly to older generations of actors, musicians and radio personalities. Prompted by Bra Len’s knowing questions, they would reveal things that I would never would have gotten them to reveal. So in all cases, I let the old man ask his questions. Of course ignoring those I thought did not add value to the story, while at the same time quietly valuing the ones I found useful. This is thanks to the many years that Bra Len spent in journalism.

Bra Len who hails from the Vaal Triangle region as we called it then, is indeed a veteran of photojournalism. His dates back to the height of apartheid in the 70s and 80s, working for publications such as The Golden City Post, and later Sowetan, where I found him in the newsroom in 1998. Battle-beaten and hardened, I found him there with other veterans.

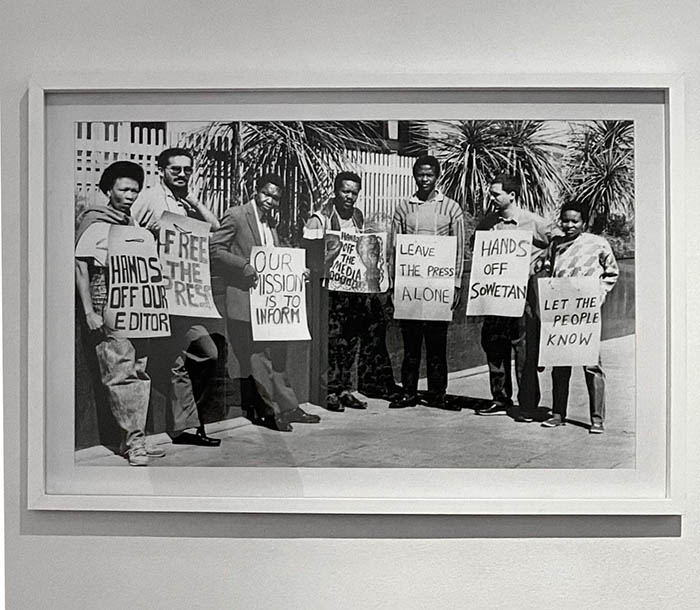

These legendary newspapermen included Mbuzeni Zulu, the late Pat Seboko, the late Moffat Zungu, Antonio Muchave and Peter Mogaki. These photojournalists shaped an alternative, rather counter narrative about the effect and impact of apartheid on black lives in the township, different from the one offered by the apartheid government. They did this using the art of photography to communicate the struggles of black township residents in the face of the socials and political difficulties they found themselves in.

These Photojournalists also lived to shape the narrative about the new South Africa, and therefore their photographic archives is very valuable. It tells the history of this country from a black perspective. Exhibiting these archival materials in the form of exhibitions open to the public, would enrich many today. Therefore Bra Len’s series of exhibitions he has embarked on after retirement, is very important. It needs to be supported by those who hold the purse strings as this series is important as a public education tool. This should be an inspiration to many photographers who went to battle with the likes of Bra Len as they documented the precariousness of black life during apartheid, and certainly in post-apartheid South Africa.

The other photographers that still hold onto a gold mine of their archives, too should also think about finding a way of exhibiting their photographic archives. There are many such photographers who are either after retrenchment in a battered media landscape since the advent of the digital technology impacting on the viability of traditional media, retired or retrenched, are holding onto rich photographic archives. This is now the time to share those archives with the public, and earn a living from their sweat and toiling in the battle field of journalism, dating back to the apartheid years.

This is where arts funding agencies should play their role and fund such exhibitions for the greater public good, but also ensure that the photographers earn a living even in retirement or after retrenchment. Society owes these lensmen and camera women a date. But asking that of them, the arts funding agencies that is, during a time when arts funding seems to elude many who genuinely do good work that benefits society, such as Bra Len, is a tall order.

To understand the extent of the current rot in arts funding, one just needs to read the recently released report by the Campaign for Free Expression. The State of Free Expression in South African Cultural Sector: An Investigation paints a damning picture of the environment of public arts funding in the country. In such an environment, public money that should fund good projects with potential for real impact on society ends up funding phantom projects or projects of those connected to officials in funding agencies.

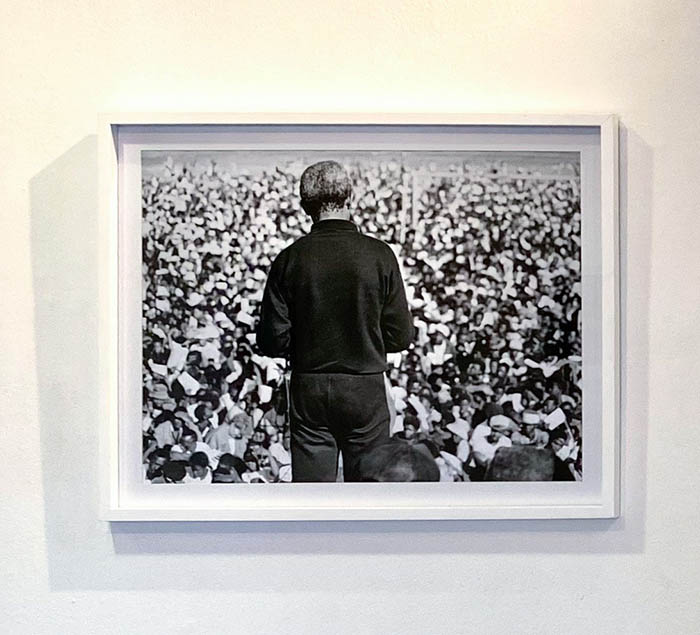

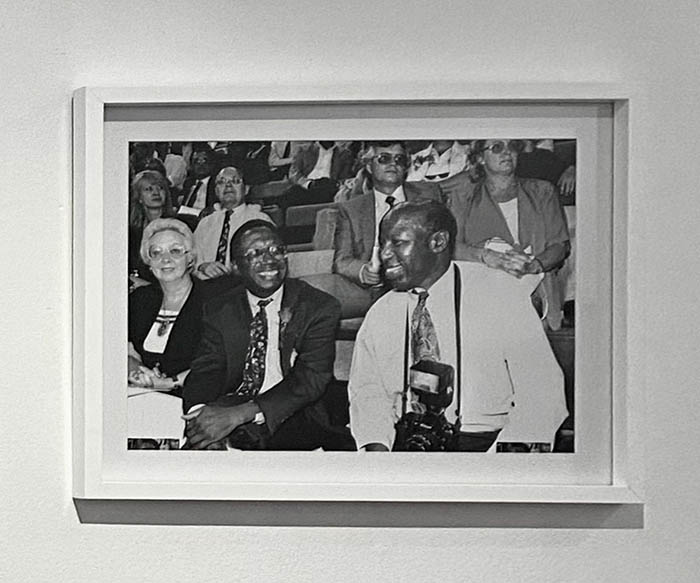

However with or without resources, Bra Len has managed through his Len Kumalo Foundation, with the assistance of his visual art lecturer daughter Nonkululeko Kumalo, to put together two editions of this series. The first happened at the North West University Gallery last year. Currently another edition is on at Umhlabathi in Newtown. The exhibition that showcases Bra Len’s photographic archives dating back to the apartheid days to post-apartheid South Africa, is a compelling viewing experience. Bra Len has captured South African life in a gripping manner. The pictures on exhibit range from those capturing an intimate case of Winnie Mandela kissing the late former President Nelson Mandela, to those showing ordinary life in the townships.

The exhibition opened on Saturday, May 27, 2023, and was well attended. The space, Umhlabathi itself, since it opened its doors to the public last year as a home for a group of independent photographers, who have their studios there as well as a gallery space, is increasingly becoming a popular space. Especially whenever there is an exhibition. Interestingly, perhaps out of curiosity, the youth from inner city Johannesburg and the surrounding townships are attracted to the Umhlabathi’s events.

Len Kumalo’s exhibition is currently on at at 2 Helen Joseph Street in Newtown, Johannesburg., Newtown.