South Africa’s urban black middle class folk reflect on issues of race, identity and politics in new book

Book Title: The Lives of Black Folk

Edited by: Kulani Nkuna

Publisher: Culture Review

Reviewer: Edward Tsumele, CITYLIFE/ARTS Editor

“Ka hisa (It is hot in XiTsonga, my translation). We are standing at the threadbare door of a shack containing the smell of an embroidered concoction of bodily sweat, weed and sex. Zito, a panel beater par excellence, is all smile,0wearing a sheen of an afterglow stemming from a sexual encounter that concluded just 10 minutes before our arrival. As per usual, he lights up a joint to calm himself, the spot still reeking like a scene from a Hillbrow brothel. The body odour is exacerbated by the unwavering heat, which seems to have deposited itself on Zito’s shack.

“I can feel myself getting darker,” says Zito about his decision to stay in his overextended shack-rather than venture outside. How Zito can get darker than he already is, is a question for the ancestors to answer, but we indulge him. Maybe it’s the weed. Luckily, he gets a call and he has to go and finish a paint job on a taxi that the owner needs done post haste.

“Outside Zito’s home it is a crap yard somewhere in Meadowlands, Soweto. Scrap metal, discarded cars and all forms of broken parts greet the amorous auto-body technician, every morning when he wakes up,” writes Kulani Nkuna, the founder and publisher of Culture Review, an online publication that has become a voice of mainly black writers angry with the black condition in contemporary South Africa.

Here he is writing in a newly published anthology of reflective, essays, articles, opinion pieces, poetry and art works by various contributors. The title of the book is The Lives of Black Folk, edited by Nkuna.

This except from Nkuna’s article titled Scrap Yard Blues: After Christmas, is about two motor technicians, Zito and Tony, originally from Mozambique and who are earning a living on the periphery of the South African mainstream economy by fixing people’s cars in the informal sector, is from a newly published book titled The Lives of Black Folk. Scrap Yard Blues: After Christmas, is a reflective piece on the wretched lives of especially African immigrants and the precarious position they often find themselves in, in South Africa, including scraping out a living mainly in the informal economy, which is unregulated and extractive both in nature and character Their relationship with their hosts is also fraught with contradictions, of both admiration and hostility, creating uncertain future in a country that both loves them and hates them at the same time, depending on a prevailing set of circumstances and situations that produce a certain particular outcome of their relationships.

This book, which is constituted by articles previously published in Culture Review, by various contributing black writers, is in many ways, a reflection of what mainly black, young and middle class professionals, young academics and young writers, feel about where South Africa is at, economically, socially and politically. Reading this book, one does not help but feel the vibrating voice of anger, disappointment and, a hunger for something more from the republic that was constructed in 1994 through a process of polarized and difficult negotiations between the then arch enemies, the now ruling party, the African National Congress and the then ruling white National Party .

Reading The Lives of Black Folk, feels like one is reading into the mind of a generation that collectively feels like 1994, was not actually a major revolution after all, but a false start of a revolution that never was, and therefore. never went anywhere, and has in fact left many yearning for an elusive freedom that was not delivered, and is yet to be attained.

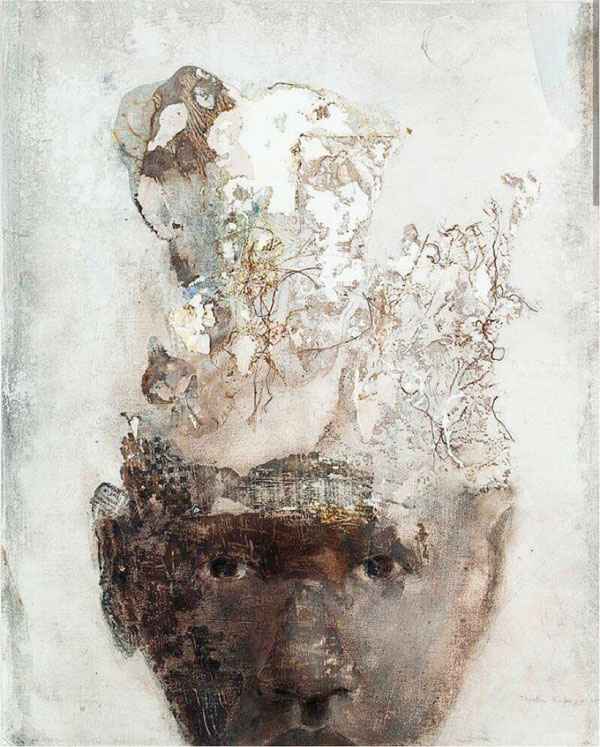

The revolution seems to have been curtailed, caught up in a web of social contradictions from which it struggles to wiggle itself out and deliver the promised land to a generation whose forebears sacrificed so much, and in return getting a phoney freedom. A sort of fraudulent transition that has failed to give people genuine freedom from colonialism and apartheid. This is the thread that runs through most of the essays in The Lives of Black Folk, by a number of contributors. The contributors drawn from various fields – from poets, academics, lawyers, activists, politicians, media, artists, essayists, pastors to anything in between are as follows: Wanelisa Xaba, Ayanda Mabulu, Thonton Kabeya, Rose Modise, Funzani Mtembu, Perfect Hlongwane, Naledi Yaziyo, Maureen Sithole, Masello Motana, Tseliso Monaheng, Mbe Mbhele, Nondumiso Msimanaga, Sive Mqikela, Percy Mabandu, Mpho Mtsitle, Makhafula Vilakazi, Pastor Xola Skosana, Tshiamo Malatji, Ziyana Lategan, Shaun Danisa, Ziphozakhe Hlobo, Palesa Nqmbaza, Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni, Katlego Tapala, Sinethemba Sankara Bizela, Thando Sipuye, Nlevis Qekema, Charles Nhamo Rupare and Veli Mbele,

The articles touch on several themes, ranging from race, identity, culture, love, gender and politics, and the selection of the articles is quite representative, when it comes to gender diversity and the issues thar are discussed.. All the articles generally assume the tone of anger and disappointment and a yearning for something more fulfilling than what is attainable when it comes to black aspirations in current contemporary South Africa.

The features by the contributors are delivered in diverse registers, from academic register to popular tone, and the manner of delivery is multi-disciplinary, such as through poetry, painting, essays and prose, reflective opinions and analysis. In some cases, the medium of delivery is through art works, such as paintings and graphics.

“Woke people say we, Black people, carry intergenerational trauma. I believe we also carry trauma and love.I loved you with the intensity of my abandonment childhood trauma. Most importantly, I loved you with all the weight of my lesbian great, great, grandmother’s inhibited queer love. With all the textures of her rural sunsets. With all the sharpness of her regret, and all her deep orange sadness over unrequited love. I included you in a private conversation between me and my ancestors,” writes contributor Wanelisa in a piece titled The Gay-est Love Letter.

“Let’s be blunt here. Life has been shit for black people for a very long time. Anything that threatens the end of the world is not altogether a bad thing, for a people whose existence is characterised by misery-misery uninvited, undeserved. A disturbance o ritual is not misfortune, for a people whose imposed ritual is one trapped within a schema of suffering, suffering unrelenting..It is as it was for us,” writes Mbe Mbhele in a piece titled A Disturbance of Ritual.

Some of the essays are reflective of several layers of black people’s often precarious existence and experiences in a world held firmly by capitalism.

“The ancestors say we were once windsurfers, roaming the earth, enjoying its bounty and healing ourselves with its knowledge. We lived in perpetual motion, transcending spoken words and feeding off the rhythmic vibrations that radiated from echoing voices of young boys herding cattle, or from palms, of mothers breast-feeding children, vibrations from the backs of our fathers tilling the land. We knew where we belonged. We always returned there. We were true to our past, comfortable in our present, and eager for our future,” reflects Charles Nhamo Rupare in an essay called We Are Not A People of Yesterday: A Memory Lost To Time.

Some essays are reflective of the issues of racialised inequalities that still bedevil contemporary South Africa, a legacy of a racially segregated society. The case in point here is an essay titled A Letter to All the White Women Whose Panties and Bras I have Won, by Palesa Nqambaza.

“Dear White woman. Thank you for your panties, for your bras, for your underwear. You do not know me, nor do I know you, but our butts share something very intimate. They have enjoyed –mine endured the covering of the same pair of panties, and later as we grew our breasts came to share a similar bond as bras became a necessity for us both. Many women in my family have worked for you as domestic workers. My grandmothers, my aunties, since you were an infant. They raised you until they were ultimately employed by you. You in turn have raised my bum, Yes, white woman, you are my bum’s keeper.

“As a good madam would, for years you gave the women in my family the clothes you no longer wanted, skirts, dresses, pants, shirts, bras, and your panties. It is almost as though you always knew that I existed. I say this because of course you knew the tiny diamante string thong held together by a miniscule butterfly, was too small for my auntie, whose full wide hips bore testament to the many children she birthed and raised. You knew that she would not wear them, but the meager wages you paid her testified that she knew someone who would. You didn’t need to see me to know of me. I am a product of your exploitation,” Palesa charges in her piece that talks to the issue of how intergenerational poverty in black society for generations defined power relationship between black women and their white employers.

Because the contributors to this anthology, The Lives of Black Folk, are young, black educated and middle class, it may be concluded that they reflect in the main, the feelings of their class in contemporary South African society, about where the country is at today, 27 years after the birth of the ‘Rainbow Nation’.

The Lives of Black Folk, is therefore, a useful resource for those seeking to understand the attitude of the black, educated urban based middle class of contemporary South Africa, with regards to issues of race, identity, gender politics, the economy and a variety of other issues that are of concern to that population segment in South Africa today.

.To place an order for The Lives of Black Folk,, send an email to Kulani at kulaninkuna1@gmail.com.

The book costs R220 excluding delivery costs which vary depending on your location.