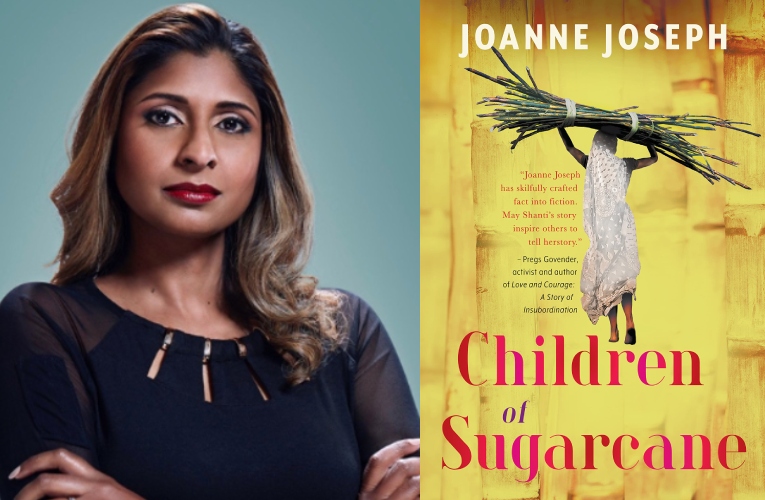

Win or lose, Joanne Joseph’s heroine stands far taller than the sugarcane searing her hands

By Jojokhala Mei

The historical novel Children of Sugarcane (2021) is an unexpected fictional bolt of lightning about the ignored personalized life of an Indian indentured labourer in South Africa of the 1800s. Better still, it is told by a woman, the celebrated journalist Joanne Joseph. And best of all, it tells novel fictitious life story of a heroine, Shanti; and inspired by her own maternal great grandmother indentured life.

For the season of new beginnings Children of Sugarcane is worth a revisit if you’ve read it before, or worth a deep entertaining and enlightening dive to contextualise what University of Natal Sociology lecturer, Kathryn Pillay, in her article amaNdiya, They’re not South Africa’ Xenophobia and Citizenship’ elabotaes: ‘The language of xenophobia towards this group of in South Africa has been consistently employed in the social and political sphere from the time of the first group indentured Indians arrived on the shores of the shores of the British Colony in 1860. Between 1860 and 1910 blatant expressions of xenophobia towards indentured labourers and others from India were prevalent in the media and political discourse, and were ultimately written into legislation, thus preserving inequality in colonial society.’ (Living Together, Living Apart (2017).

Shanti’s pitifully innocent escape from a mercilessly arranged marriage in the Indian region of Madras Presidency is spun with virulent images and vivacious evocative language of rural India. She volunteers to be an indentured sugarcane cutter a whole world apart across the Indian Ocean in the Colony of Natal. On the British colonizers’ ship her innocence is shattered to witness, amongst a sea of atrocities, ‘’Nagamah … a frail, dark-skinned, mouse-like woman … lashed with a cane several times, often for failing to bathe (because) she hated having to clean herself in the open area where the ship’s men leered at her.

… For a moment no one recognised Nagamah. Her face had been splashed white with the paint used to coat the ship. … Her hands were tied tightly behind her back. Her limp breasts were exposed, and on her bare chest was painted the face of a pig. We stood there, stunned, as Rawlings paraded Nagamah around the deck for us all to see. …None of us could look at her. It would only have humiliated her more. That day I felt a seed of hatred germinate in me. I saw what Rawlings was doing. He wanted us to participate in the degradation of one of our own, And, in that act, he not only debased Nagamah – he humiliated all of us. In all the time that I had lived in the Madras Presidency I had never heard or witnessed anything so shocking.

But far, far worse was still to befall them on the sugarcane plantations od Natal Colony. If Shanti’s language was to be later used against her ‘voracious’ and curt, it makes for devastatingly sharp and honest first-person observation throughout the novel.

Do not be misled, because amid the worsening life on the Colony of Natal sugarcane plantations blooms humanity, news from home, humour, lovely reunions, and tender lov, amongst the labourers.

But far deep into sugarcane life the deft authorial voice shows itself again in Shanti’s first confused and confusing surreal description of her rape by the British plantation owner, Wilson.

Nevertheless, there is a sad surprise, but flash magical twist to the story as Shanti takes her fate into her own hands; to emerge victorious at the end. One step ahead of the University of Cape Town’s Brenda Cooper’s observation in The Routledge Encyclopedia of African literature 2003), edited by Simon Gikandi of the University of Michigan in the USA, that:

‘If magical realism attempts to capture reality by way of a depiction of life’s many dimensions, seen and unseen, visible and invisible, rational and mysterious, such writers walk a tightrope between capturing the reality and providing the exotic escape from reality desired by some of their western readership.’

All in all, Shanti’s is a keepsake story, to keep all your senses open to surprise humanity even in the darkest times. A reminder that ‘indentured labourer’ was only a polite word for slavery.

Email: jojokhalam2gmail.com